Learn practical techniques for creating instruction-tuning datasets. Covers human annotation, template-based generation, seed expansion, and quality filtering.

This article is part of the free-to-read Language AI Handbook

Choose your expertise level to adjust how many terms are explained. Beginners see more tooltips, experts see fewer to maintain reading flow. Hover over underlined terms for instant definitions.

Instruction Data Creation

As we discussed in the previous chapter on instruction following, the key innovation that transforms a language model into an instruction-following assistant is not architectural. It's the training data. A model learns to follow instructions by seeing thousands of examples that demonstrate the desired behavior: clear tasks paired with helpful, accurate responses. This chapter explores the practical challenge of creating such data at scale, examining the techniques that have enabled researchers to build the datasets that power modern AI assistants.

Creating high-quality instruction data is both an art and an engineering challenge. You need sufficient volume to cover diverse tasks, enough quality to teach proper behavior, and adequate diversity to generalize beyond memorized patterns. The field has developed several complementary approaches to meet these requirements: human annotation for quality, template-based generation for scale, seed task expansion for diversity, and quality filtering to maintain standards across all sources. Each approach has its own strengths and limitations, and understanding these tradeoffs is essential for you.

Human Annotation

Human annotation remains the gold standard for instruction data quality. When a skilled annotator writes an instruction and its response, they bring world knowledge, common sense, and an intuitive understanding of what makes a response helpful. The earliest instruction-tuned models, including InstructGPT from OpenAI, relied heavily on human-written demonstrations. This reliance on human expertise highlights that instruction following depends on human communication patterns and preferences that automated methods struggle to capture.

Annotation Guidelines

Creating effective annotation guidelines requires balancing specificity with flexibility. Guidelines that are too rigid produce formulaic responses that lack naturalness. Guidelines that are too loose produce inconsistent data where annotators interpret tasks differently. Finding the right balance is itself a design challenge that requires iteration and feedback from annotators who work with the guidelines in practice.

Effective guidelines typically specify:

- Response format expectations: Should responses include explanations, or just direct answers? Should they acknowledge uncertainty? These choices shape the personality and communication style of the resulting model.

- Tone and style: Formal or conversational? Verbose or concise? The tone established in training data carries through to the model's behavior with you.

- Handling edge cases: What should annotators do with ambiguous requests, harmful queries, or questions outside their expertise? Clear guidance prevents annotators from improvising inconsistently.

- Quality thresholds: What makes a response "good enough" versus requiring revision? Concrete examples of acceptable and unacceptable responses help calibrate annotator judgment.

The Dolly dataset from Databricks provides a useful example. Their guidelines instructed annotators to write creative, brainstorming, question answering, classification, summarization, and information extraction tasks, covering a spectrum of instruction types while giving annotators freedom within each category. This approach recognized that creativity flourishes within constraints, and that annotators need enough structure to be consistent while retaining enough freedom to produce natural, varied examples.

Quality Control Mechanisms

Human annotation introduces human variability. Different annotators bring different writing styles, knowledge levels, and interpretations of guidelines. Quality control mechanisms help maintain consistency across a diverse pool of contributors and ensure that the resulting dataset reflects the intended quality standards rather than the idiosyncrasies of individual annotators.

- Inter-annotator agreement: Having multiple annotators label the same examples reveals disagreements that indicate unclear guidelines or genuinely difficult cases. When two annotators produce very different responses to the same instruction, it signals either an ambiguous task or a need for guideline refinement.

- Expert review: Senior annotators review a sample of outputs, providing feedback and identifying systematic issues. This creates a feedback loop where common problems are caught early and addressed through guideline updates or additional training.

- Iterative refinement: Guidelines evolve based on observed problems, with regular calibration sessions to realign annotator understanding. This ongoing process acknowledges that annotation guidelines are living documents that improve through use.

Cost and Scale Tradeoffs

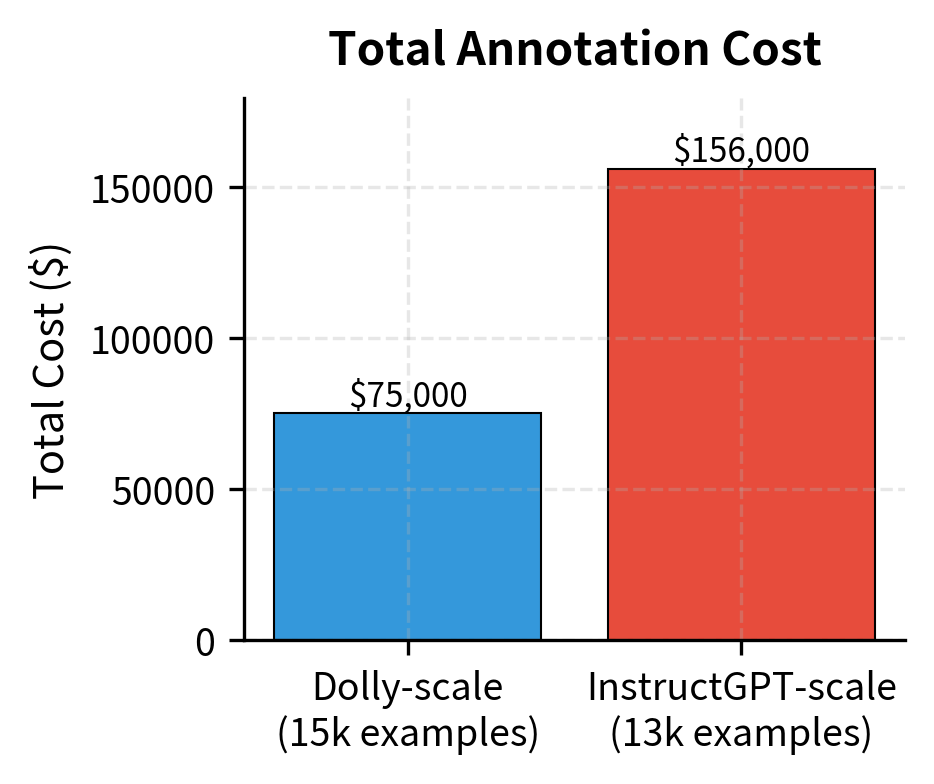

Human annotation is expensive. Professional annotators cost $15-50+ per hour depending on the task complexity and required expertise. A single high-quality instruction-response pair might take 5-15 minutes to create, putting the cost per example between $1-15. These costs accumulate quickly when building datasets of any meaningful size.

This cost creates a fundamental tradeoff: you can have either a small dataset of exceptional quality or a larger dataset of variable quality. The InstructGPT paper used only about 13,000 human demonstrations, a tiny dataset by pre-training standards, but each example was carefully crafted by selected contractors who underwent extensive training. This choice reflected a bet that quality would matter more than quantity for teaching instruction-following behavior.

These costs explain why purely human-annotated instruction datasets remain relatively small. Even well-funded projects typically cap at tens of thousands of examples, not the millions common in pre-training. This scale limitation motivates the alternative approaches described in the following sections, each of which trades some aspect of human quality for the ability to generate data more efficiently.

Template-Based Generation

Template-based generation addresses the scale limitation of human annotation by programmatically converting existing NLP datasets into instruction format. The insight is that tasks like sentiment classification, question answering, and summarization already exist in large annotated datasets. They just need to be reframed as natural language instructions. This reframing transforms supervised learning labels into the kind of instruction-response pairs that teach a model how to follow your requests.

Converting Existing Datasets

Consider the Stanford Sentiment Treebank, a dataset with sentences labeled as positive or negative. In its original form, an example looks like:

text: "This movie is a triumph of style over substance."

label: negative

With templates, we can transform this into an instruction-following example:

instruction: "Classify the sentiment of the following movie review as 'positive' or 'negative'."

input: "This movie is a triumph of style over substance."

output: "negative"

This transformation preserves the supervised signal while presenting it in a format that teaches instruction following. The model learns not just to classify sentiment, but to respond appropriately when you ask it to perform classification. The distinction matters: instruction following requires understanding what is being asked, not just producing the correct label.

The output shows how a single input "The acting was superb..." generates diverse training examples. By seeing the same content formatted differently, the model learns that the task of sentiment analysis is independent of the specific prompt wording. This robustness to phrasing variations is essential for real-world deployment, where you express the same intent in countless different ways.

Template Design Principles

Effective templates share several characteristics that make them valuable for instruction tuning. Understanding these principles helps you create better templates and recognize quality issues in existing template collections.

Templates should vary in phrasing to prevent the model from overfitting to specific wordings. If every sentiment classification instruction starts with "Classify the sentiment," the model may fail when encountering "What's the tone of this text?" Variation teaches the model to recognize the underlying task regardless of surface-level differences in how it is expressed.

Templates should sound natural, as if you wrote them. Stilted or overly formal phrasing creates a mismatch between training data and your queries. The goal is to expose the model to the kinds of requests it will receive in practice, not to construct perfectly grammatical but unnaturally precise instructions.

Templates should include diverse output formats: sometimes a single word, sometimes a full sentence, to teach flexible response styles. You have different preferences for response verbosity, and a well-trained model should be able to adapt. You might want a quick answer, or you might appreciate context and explanation.

The FLAN collection demonstrates these principles at scale. It includes templates for over 60 datasets spanning question answering, sentiment analysis, natural language inference, coreference resolution, and many other tasks. Each dataset has multiple templates, creating millions of instruction examples from existing supervised data. This massive scale would be impossible to achieve through human annotation alone.

These examples illustrate how the same underlying logical relationship can be cast as different instructional tasks, ranging from simple classification to more complex reasoning queries. By varying the prompt structure, the model learns to identify the core task regardless of how it is phrased. The logical relationship between premise and hypothesis remains constant, but the way we ask about that relationship changes. This teaches the model that natural language inference is a concept, not a specific prompt format.

Limitations of Template-Based Generation

While template-based generation provides scale, it has significant limitations that you must understand and address. Recognizing these limitations helps you make informed decisions about when template-based data is appropriate and when other approaches are needed.

The resulting instructions tend to be formulaic, lacking the variety of your real queries. Templates follow patterns, and no matter how many templates you create, they cannot capture the full messiness and creativity of how humans actually phrase requests. You make typos, use slang, provide unclear context, and phrase things in unexpected ways. Template-based data, by contrast, is clean and predictable.

Templates also inherit the task distribution of existing datasets, which skew heavily toward classification and extraction tasks rather than open-ended generation. The NLP community has historically focused on tasks with clear right answers that enable straightforward evaluation. This means template-converted data overrepresents tasks like sentiment classification, named entity recognition, and question answering, while underrepresenting creative writing, advice-giving, and open-ended exploration.

Perhaps most importantly, template-based data doesn't teach creative or conversational abilities. A model trained only on converted classification datasets won't learn to write poetry, explain concepts in simple terms, or engage in multi-turn dialogue. These capabilities require training data that demonstrates them explicitly. Template-based generation works best as a complement to other data sources, not a replacement for them.

Seed Task Expansion

Seed task expansion bridges the gap between expensive human annotation and mechanical template conversion. The approach starts with a small set of carefully crafted seed examples, then uses various techniques to expand this seed into a larger, more diverse dataset. This method preserves the quality and naturalness of human-written examples while achieving scale through systematic augmentation.

The Seed Set Philosophy

A good seed set is small but carefully curated. The philosophy behind seed expansion recognizes that a few excellent examples, chosen to cover the space of possible instructions, can serve as anchors for generating many more examples. The key is ensuring that the seeds represent the diversity you want in the final dataset.

A well-designed seed set should demonstrate:

- Task diversity: Including examples from many task categories (creative writing, question answering, coding, analysis, etc.) ensures that expansion can generate examples across the full range of desired capabilities.

- Format diversity: Showing different input/output structures (single-turn, multi-turn, with/without context) teaches the model that instructions can take many forms.

- Complexity range: Spanning from simple lookups to multi-step reasoning ensures the model learns to handle both easy and difficult requests.

- Style variety: Demonstrating different appropriate tones and verbosity levels teaches the model to adapt its communication style to different contexts.

The Self-Instruct paper, which the next chapter explores in detail, started with just 175 seed tasks. Each seed was written to be distinct, covering a different aspect of instruction-following capability. This small but diverse seed set enabled the generation of tens of thousands of additional examples while maintaining quality and coverage.

Augmentation Techniques

Once you have a seed set, several techniques can expand it without requiring additional human annotation. These techniques leverage the structure and content of existing examples to generate new variations that preserve the essential characteristics while adding diversity.

Paraphrasing generates alternative wordings for existing instructions. The goal is to teach the model that the same task can be expressed in many different ways. You might say "Write a poem" or "Compose a poem" or "Create a poem," and the model should recognize these as equivalent requests.

The rule-based approach generates several valid syntactic variations of the original instruction, expanding the dataset without changing the semantic intent. This teaches the model that different queries you write can map to the same underlying task. While rule-based paraphrasing is limited in its flexibility, it provides a foundation that can be enhanced with more sophisticated language model-based paraphrasing techniques.

Input variation creates new examples by substituting different inputs into the same instruction template. This technique recognizes that many instructions follow reusable patterns where the specific content can change while the task structure remains constant. A request to "write a Python function" can apply to countless different programming problems.

Diversity Sampling

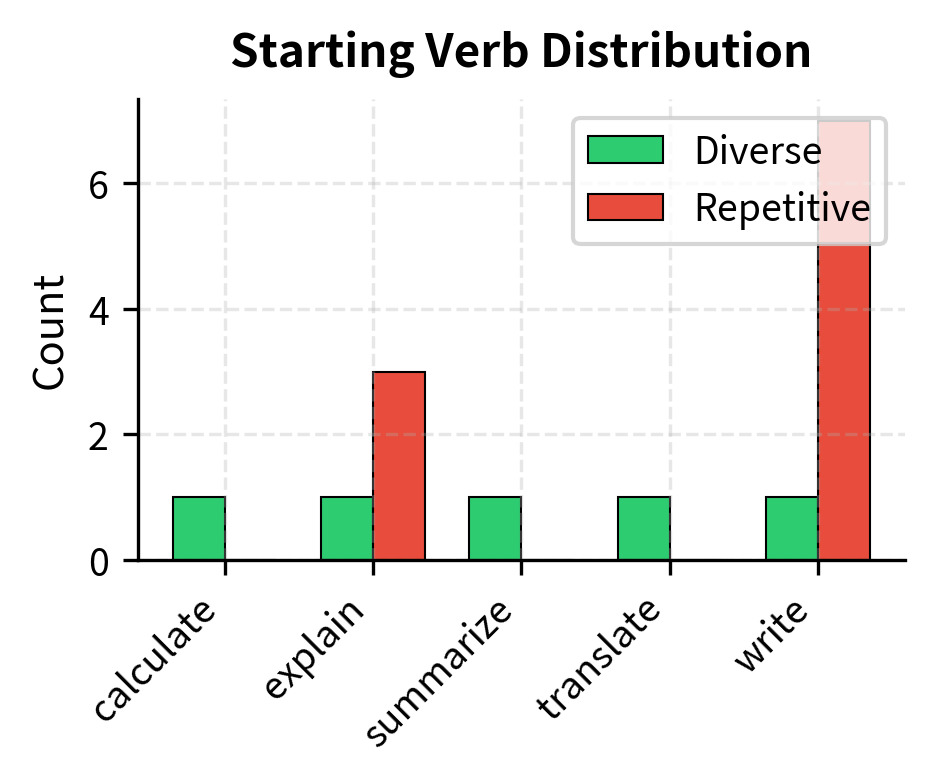

When expanding from seeds, maintaining diversity is crucial. Without careful sampling, expansion tends to produce many similar examples clustered around popular seed patterns while neglecting rarer but important task types. This clustering reduces the effective size of the dataset and can lead to models that perform well on common tasks but poorly on less frequent ones.

Diversity sampling techniques help ensure balanced coverage:

- Category balancing: Ensuring expanded data maintains representation across all task categories prevents any single category from dominating the training signal.

- Embedding-based filtering: Using text embeddings to detect and remove examples too similar to existing ones keeps the dataset diverse at a semantic level.

- Verb/topic tracking: Monitoring the distribution of instruction verbs and topics to prevent overconcentration helps identify when expansion is gravitating toward particular patterns.

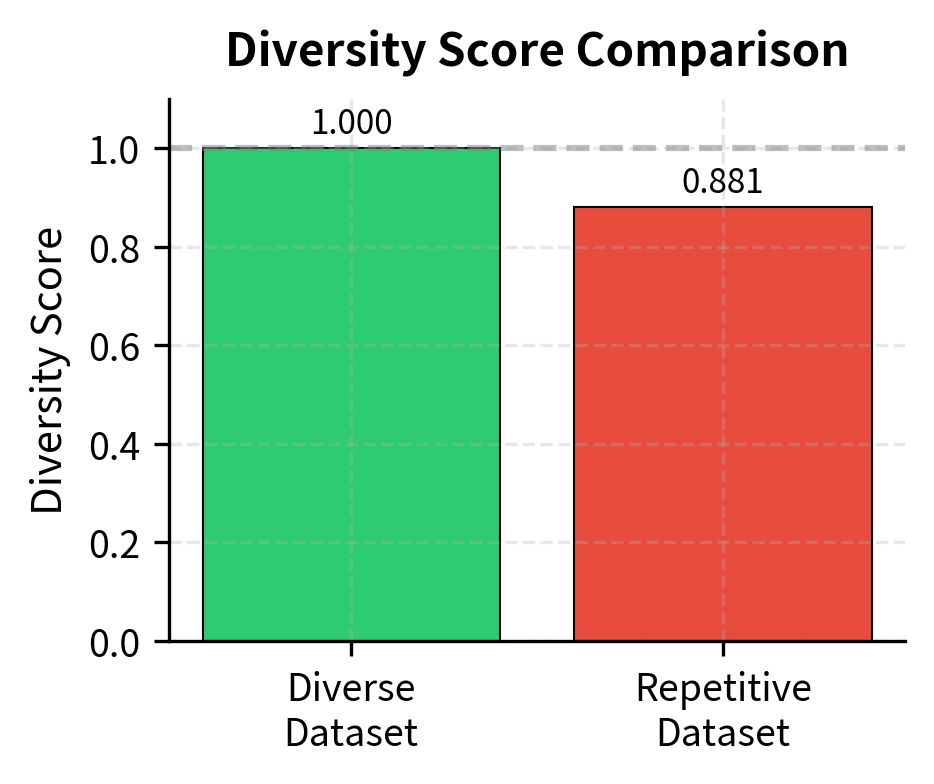

The diversity score captures how evenly distributed the instruction patterns are. A dataset dominated by "Write..." instructions scores lower than one with balanced representation across different task types. This metric provides a quantitative way to track diversity during expansion and flag potential problems before they affect model training.

Quality Filtering

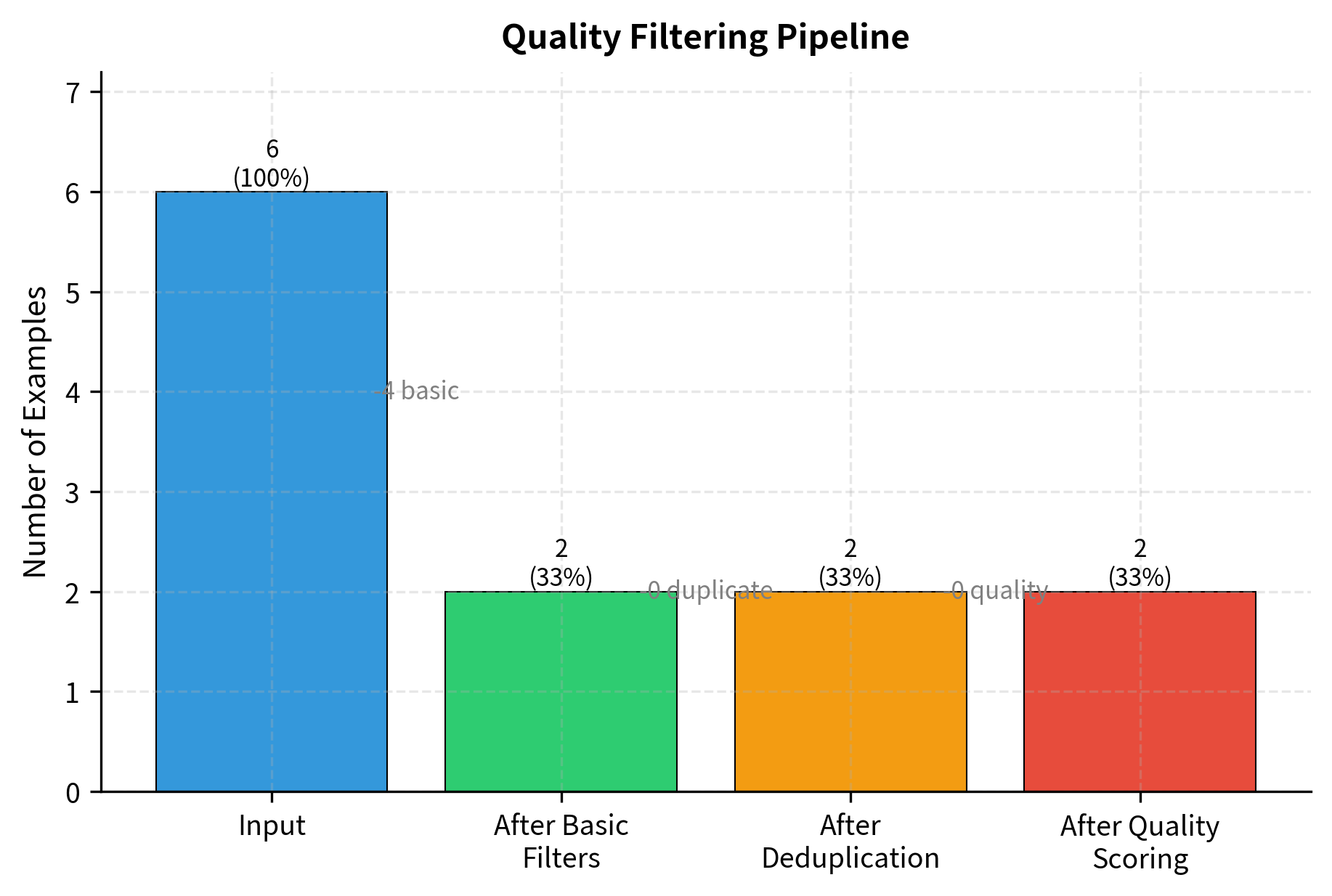

Whether data comes from human annotation, template conversion, or seed expansion, quality filtering is essential. Raw data inevitably contains errors, duplicates, and low-quality examples that can harm model training. A systematic filtering pipeline removes these problems while preserving valuable examples. The goal is to maximize the signal-to-noise ratio in the training data, ensuring that every example the model sees contributes positively to its learning.

Length and Format Filters

Basic heuristics catch many obvious problems. These filters are fast to compute and can be applied to millions of examples without significant computational cost. While simple, they remove a substantial portion of problematic data before more expensive filtering stages.

Deduplication

Duplicate or near-duplicate examples waste training compute and can cause the model to memorize specific examples rather than learn general patterns. Deduplication operates at multiple levels, from exact string matching to semantic similarity detection. Each level catches different types of redundancy.

Exact deduplication removes identical instruction-output pairs. This is the simplest form of deduplication but catches surprisingly many duplicates, especially in data generated through automated expansion or scraped from multiple sources.

Removing exact duplicates reduces the dataset size but ensures that the model encounters unique examples, preventing overfitting to repeated tokens. In this case, identical and case-variant duplicates were successfully consolidated. Note that examples with the same instruction but different outputs are preserved, as they represent genuinely different training signals.

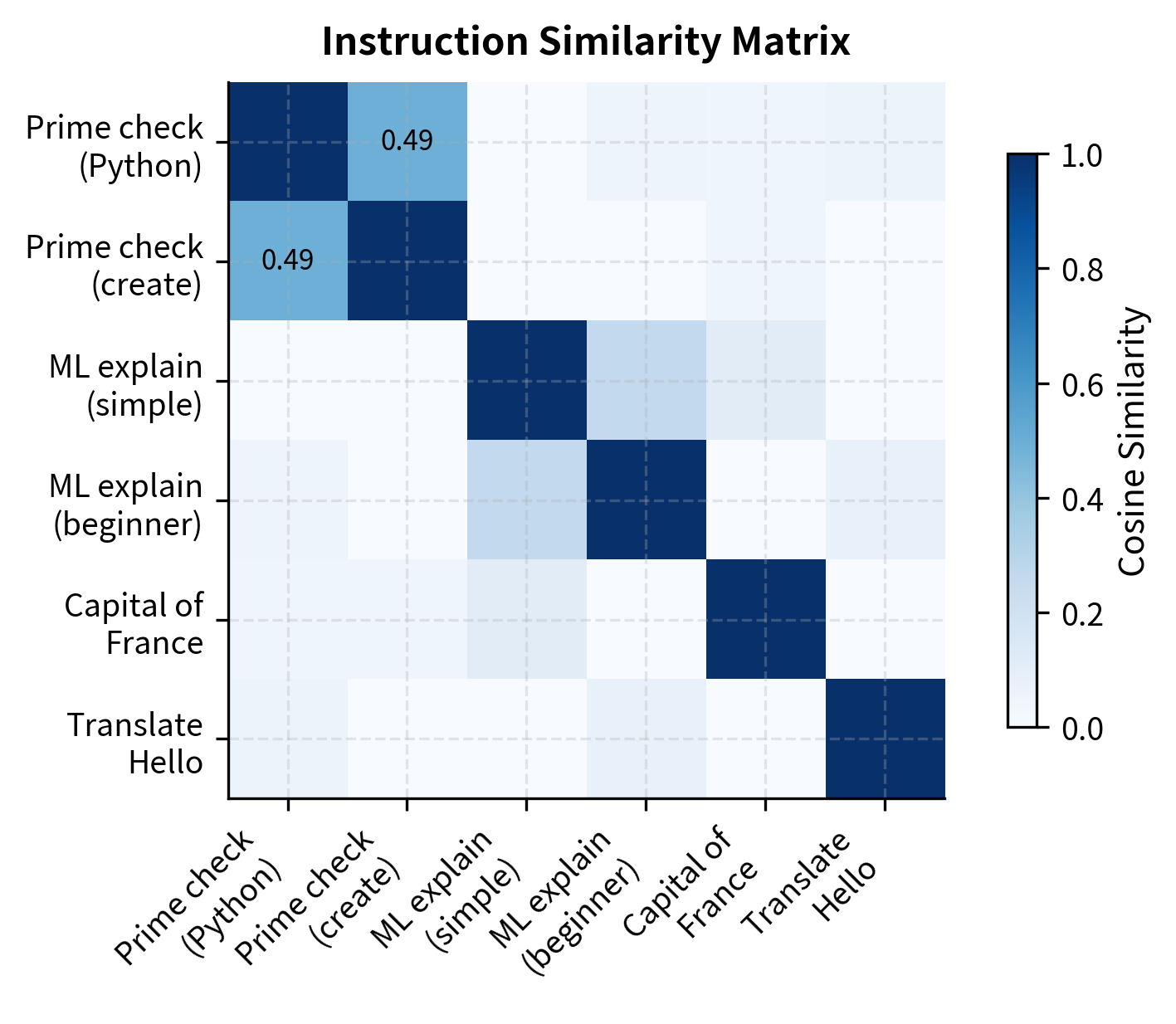

Near-duplicate detection catches examples that are semantically identical but superficially different. Two instructions might ask the same thing in slightly different words, and training on both provides little additional value. This typically uses embedding similarity to identify examples that are close in semantic space.

The high similarity scores identify pairs that differ only slightly in wording, allowing us to flag potential redundancies that exact matching misses. Filtering these near-duplicates ensures the training compute is spent on genuinely distinct examples. The threshold for near-duplicate detection requires careful tuning: too low and you remove legitimate variations; too high and redundant examples slip through.

Model-Based Quality Scoring

Human-written heuristics can only catch obvious problems. For subtler quality issues, including unclear instructions, factually incorrect outputs, or stylistically poor responses, model-based filtering provides more nuanced assessment. These approaches leverage the judgment capabilities of language models to evaluate aspects of quality that are difficult to capture in simple rules.

The approach uses a language model to score or classify the quality of each example. The model can be prompted to evaluate various dimensions of quality: clarity of the instruction, helpfulness of the response, correctness of any factual claims, and appropriateness of the tone.

The simulated scores reflect the heuristic that detailed, well-structured responses (like the relativity explanation) are more valuable for instruction tuning than brief or generic outputs. By scoring examples, we can filter out low-value data or curriculum-train the model on high-quality examples first. This curriculum approach exposes the model to the best examples early in training, establishing good patterns before introducing noisier data.

In production systems, quality filtering often uses a tiered approach: fast heuristic filters remove obvious problems, then more expensive model-based scoring handles the remaining examples. This balances thoroughness with computational cost. Running a language model over every example is expensive, so reserving model-based filtering for examples that pass initial heuristic checks makes the pipeline practical at scale.

Building a Complete Filtering Pipeline

Combining all filtering stages into a unified pipeline ensures consistent quality across the dataset. A well-designed pipeline applies filters in order of computational cost, with cheap heuristic filters first and expensive model-based scoring last. This design minimizes the total compute required while still achieving thorough filtering.

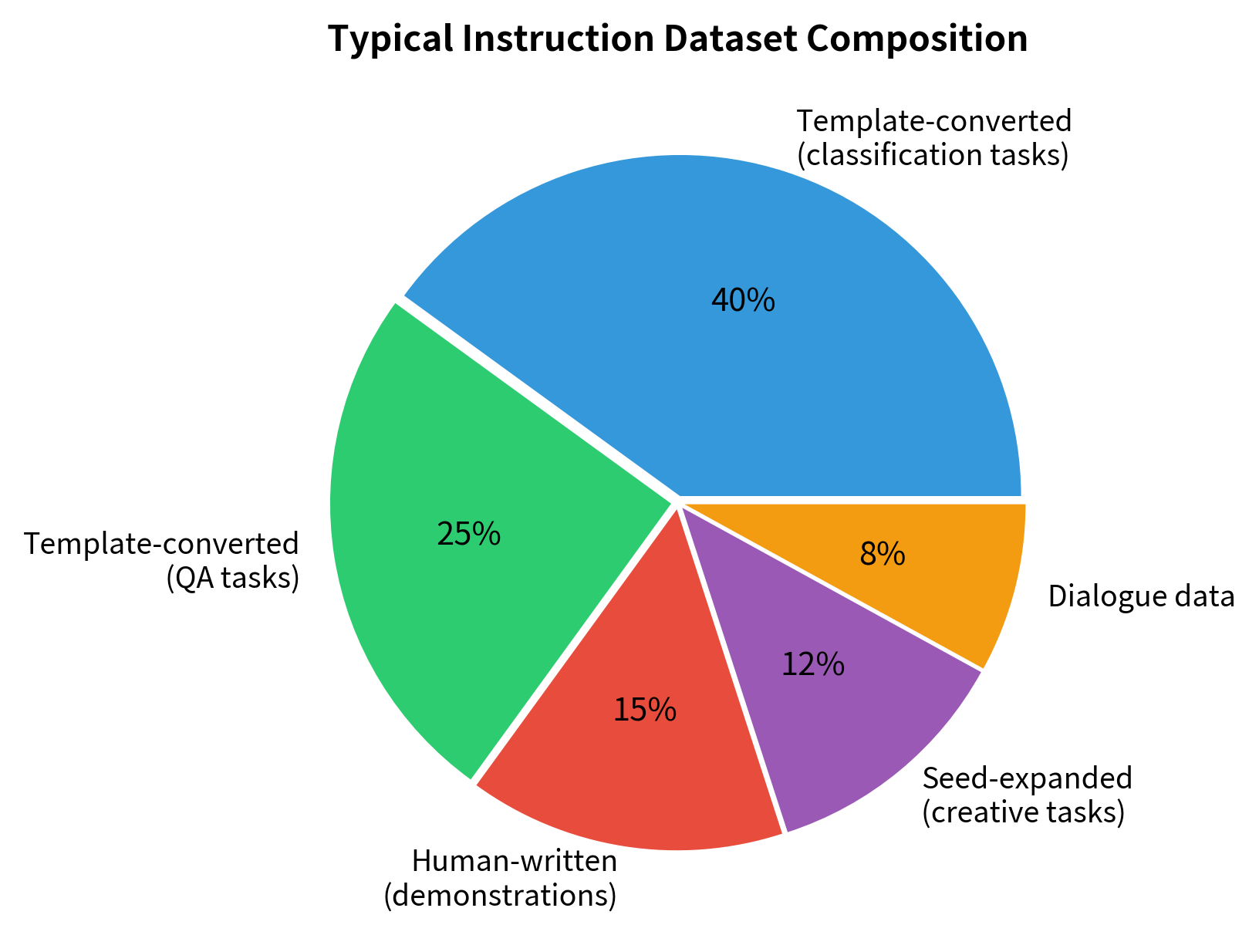

Combining Data Sources

Real instruction-tuning datasets rarely use a single creation method. Instead, they combine multiple sources to balance their respective strengths and weaknesses. This combination recognizes that no single approach excels at everything: human annotation provides quality but not scale, templates provide scale but not naturalness, and seed expansion provides a middle ground that still requires careful curation.

| Source | Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|

| Human annotation | High quality, natural phrasing | Expensive, limited scale |

| Template conversion | Large scale, task diversity | Formulaic, limited creativity |

| Seed expansion | Balance of quality and scale | Requires good seeds, can drift |

The FLAN-T5 model, for instance, combines template-converted versions of 62 existing datasets with chain-of-thought examples and dialogue data. This mixture teaches both task-specific skills and more general conversational abilities. The template-converted data provides broad coverage of NLP tasks, while the chain-of-thought and dialogue data teach more sophisticated reasoning and interaction patterns.

This visualization highlights the strategic balance between volume (template-converted) and quality (human-written/seed-expanded) required for effective instruction tuning. While automated methods provide the bulk of the data, the smaller high-quality components are essential for steering the model's style and capabilities. The human-written demonstrations, though small in number, have outsized influence on how the model behaves, establishing patterns that the larger automated data then reinforces.

Limitations and Practical Considerations

Instruction data creation faces several fundamental challenges that you must navigate.

Quality-diversity tradeoffs are unavoidable. Human annotation produces high-quality data but struggles to cover the full space of possible instructions. Template-based methods achieve coverage but produce data that lacks the naturalness of your queries. Seed expansion can balance these concerns but requires careful monitoring to prevent quality degradation as the dataset grows. No single approach solves all problems, which is why production systems invariably combine multiple methods.

Dataset biases propagate to model behavior. If your instruction data overrepresents certain topics, phrasings, or response styles, the fine-tuned model will reflect those biases. This is particularly insidious because biases in training data are often invisible until they manifest as unexpected model behaviors in deployment. For instance, a dataset heavy on formal business writing might produce a model that struggles with casual conversation, while one focused on American English idioms might confuse you if you live in other English-speaking regions.

Scaling data creation remains expensive. Despite advances in template-based and model-assisted generation, creating genuinely diverse, high-quality instruction data still requires significant human effort. The cost estimates we calculated earlier for human annotation represent a floor, not a ceiling. Real projects often spend considerably more on iteration, quality control, and fixing problems discovered during training. This expense motivates ongoing research into more efficient data creation methods, including the Self-Instruct approach described in the next chapter.

Evaluation lags behind creation. While many techniques exist for creating instruction data, evaluating its quality at scale remains challenging. Automated metrics capture surface-level properties but miss deeper quality issues. Human evaluation is expensive and slow. This asymmetry means data problems often remain undiscovered until after a model has been trained and its behavior observed creating costly iteration cycles.

Summary

Instruction data creation bridges the gap between pre-trained language models and instruction-following assistants. This chapter covered four complementary approaches that form the foundation of modern instruction-tuning pipelines:

Human annotation provides the highest quality data but is constrained by cost. Effective annotation requires clear guidelines, quality control mechanisms, and acceptance that scale will be limited. Human-written demonstrations remain valuable for establishing quality standards and covering tasks that require genuine expertise.

Template-based generation converts existing supervised datasets into instruction format, providing scale and task diversity. Well-designed templates vary in phrasing and output format to teach flexible instruction following. However, templates produce formulaic data that lacks the naturalness of your real interactions.

Seed task expansion starts with a small set of carefully curated examples and uses various techniques to grow the dataset while maintaining diversity. Good seed sets demonstrate variety across task categories, formats, complexity levels, and styles. Expansion techniques include paraphrasing, input variation, and diversity sampling to prevent clustering around popular patterns.

Quality filtering removes problematic examples regardless of their source. A complete pipeline combines fast heuristic filters for obvious problems, deduplication to prevent memorization, and model-based scoring for subtler quality issues. Filtering statistics help identify systematic problems in data creation processes.

The next chapter explores Self-Instruct, a specific seed expansion technique that uses a language model to generate new instruction examples from a small seed set. This approach has enabled the creation of instruction datasets at scale without massive human annotation efforts, democratizing access to instruction-tuning beyond well-funded research labs.

Quiz

Ready to test your understanding? Take this quick quiz to reinforce what you've learned about instruction data creation methods.

Comments