Master RLAIF and Constitutional AI for scalable model alignment. Learn to use AI feedback, design constitutions, and train reward models effectively.

This article is part of the free-to-read Language AI Handbook

Choose your expertise level to adjust how many terms are explained. Beginners see more tooltips, experts see fewer to maintain reading flow. Hover over underlined terms for instant definitions.

RLAIF

The RLHF pipeline we explored in previous chapters relies on a critical resource: human annotators who compare model outputs and express preferences. As we discussed in the Human Preference Data chapter, collecting high-quality preference data requires careful annotator training, clear guidelines, and significant time investment. Human annotation creates a bottleneck because it scales with labor costs, whereas model capabilities scale with compute.

Reinforcement Learning from AI Feedback (RLAIF) addresses this bottleneck by replacing human annotators with AI systems. Instead of paying humans to compare outputs and select the better response, RLAIF prompts a language model to make those same judgments. This substitution improves scalability but raises questions about aligning models without direct human feedback.

The core insight behind RLAIF is that capable language models already encode substantial information about human preferences from their pretraining data. When prompted appropriately, they can articulate which responses are more helpful, which contain harmful content, and which better follow instructions. AI feedback is not identical to human feedback, but it works as a useful proxy when guided by specific principles.

The AI as Annotator Paradigm

Traditional RLHF treats human annotators as the ground truth for preferences. When a human says "Response A is better than Response B," that judgment directly shapes the reward model. RLAIF replaces this human judgment with AI judgment, but the rest of the pipeline remains largely intact. Because the architecture is preserved, the foundations of RLHF, including the Bradley-Terry model and policy optimization, apply directly to RLAIF.

RLAIF assumes that language models learn human values and preferences during pretraining. When a model reads millions of conversations, reviews, critiques, and discussions, it learns not just language patterns but also implicit norms about what constitutes helpful, honest, and appropriate communication. RLAIF leverages this embedded knowledge by prompting the model to make explicit judgments that draw on these internalized norms.

The workflow proceeds as follows:

- Generate response pairs: Given a prompt, the model produces multiple candidate responses

- AI evaluation: A language model (often the same model being trained, or a more capable one) evaluates which response is better

- Train reward model: Use the AI-generated preferences to train a reward model, just as in RLHF

- Policy optimization: Apply PPO or similar algorithms using the reward model

The key difference lies entirely in step 2. Instead of sending response pairs to human annotators through platforms like Scale AI or Surge AI, the system sends them to a language model with an appropriate prompt. This substitution makes a labor-intensive process easy to parallelize across GPUs.

A basic AI annotation prompt might look like:

Given the following prompt and two responses, which response is more helpful, harmless, and honest?

Prompt: {user_prompt}

Response A: {response_a}

Response B: {response_b}

Which response is better? Answer with just "A" or "B".

This simple approach already produces surprisingly useful signal. The prompt encodes the evaluation criteria (helpful, harmless, honest) and provides the context needed for comparison. Research from Google and Anthropic has shown that AI-generated preferences often correlate well with human preferences, particularly for clear-cut cases where one response is obviously better. The correlation tends to be strongest when quality differences are substantial, such as when one response contains factual errors or fails to address a user's question entirely.

However, naive AI annotation has limitations. The AI might have systematic biases, prefer verbose responses, or fail to catch subtle harmful content that humans would flag. These limitations motivate more sophisticated approaches, particularly Constitutional AI.

Constitutional AI Principles

Constitutional AI (CAI), introduced by Anthropic in 2022, provides a principled framework for RLAIF. Rather than simply asking an AI "which is better," CAI grounds the AI's judgments in an explicit set of principles, called a constitution. This grounding turns vague ideas of quality into concrete criteria that can be examined and refined.

In Constitutional AI, a constitution is a set of principles that guide the AI's behavior and judgments. These principles articulate values like helpfulness, harmlessness, and honesty in concrete terms that the AI can apply when evaluating or generating responses.

The concept of a constitution draws inspiration from how human societies codify their values. Just as a national constitution provides a framework for resolving disputes and guiding behavior, a CAI constitution provides a framework for the AI to resolve conflicts between competing objectives and make consistent judgments. This analogy is instructive: constitutions work not because they cover every possible situation, but because they establish principles that can be applied to novel circumstances.

A constitution might include principles like:

- "Please choose the response that is most helpful to the human while being safe"

- "Choose the response that sounds most similar to what a peaceful, ethical, wise person would say"

- "Choose the response that is least likely to encourage or enable harmful activities"

- "Choose the response that demonstrates the most careful reasoning"

Each principle targets a different dimension of quality. The first balances helpfulness against safety. The second invokes a role model heuristic, asking what an idealized person would say. The third focuses specifically on harm prevention. The fourth emphasizes reasoning quality. Together, these principles create a multi-dimensional evaluation framework that captures various aspects of response quality.

The constitution serves multiple purposes. First, it makes the values being optimized explicit and auditable. Unlike opaque human preferences that vary across annotators, constitutional principles are written down and can be examined, debated, and revised. This transparency is valuable for both technical development and broader societal discussions about AI alignment. Second, it provides consistency: the same principles apply across all evaluations, reducing the variance that comes from different human annotators having different standards. This consistency helps the reward model learn a cleaner signal, potentially improving training efficiency.

The CAI Two-Phase Process

Constitutional AI operates in two phases: a supervised learning phase and a reinforcement learning phase. This structure mirrors the RLHF pipeline, using supervised learning for data and reinforcement learning for refinement. CAI generates this data by using the model's own capabilities.

Phase 1: Critique and Revision (SL-CAI)

In the first phase, the model generates responses to potentially harmful prompts, then critiques its own responses using constitutional principles, and finally revises the responses based on those critiques. This generates training data for supervised fine-tuning. The key insight here is that a model capable of generating problematic content is often also capable of recognizing what makes that content problematic, especially when prompted with specific principles to consider.

The process works as follows:

- Generate initial response: The model responds to a prompt, potentially producing harmful content

- Self-critique: The model is prompted to identify problems with its response based on a constitutional principle

- Revision: The model revises its response to address the critique

- Iterate: Steps 2-3 can repeat with different constitutional principles

This iterative refinement mirrors how humans improve their own work through reflection and revision. By applying multiple constitutional principles in sequence, each revision addresses a different aspect of response quality. The result is a response that has been systematically improved across multiple dimensions.

For example, given a prompt asking how to pick a lock, the model might initially provide detailed instructions. The critique phase would identify this as potentially enabling harmful activities. The revision would transform the response into something that acknowledges the question while declining to provide lock-picking instructions. This revised response then becomes part of the supervised fine-tuning dataset, teaching the model through demonstration how to handle similar requests appropriately.

Phase 2: Reinforcement Learning (RL-CAI)

The second phase applies RLAIF using the constitution to generate preference labels. The model generates multiple responses to prompts, and a separate AI model (or the same model in a different context) chooses which response better adheres to constitutional principles. This phase builds upon the supervised fine-tuning from Phase 1, further refining the model's behavior through reinforcement learning.

This phase resembles standard RLHF, but with AI-generated preferences based on constitutional principles rather than human preferences collected through annotation. The constitutional principles serve the same role that annotation guidelines serve for human annotators: they define what "better" means in a way that can be applied consistently across many comparisons.

Designing Effective Constitutions

The constitution's design significantly impacts the resulting model behavior. A poorly designed constitution can lead to models that optimize for superficial features or that fail to capture important aspects of alignment. Anthropic's research revealed several insights about effective constitutions:

Specificity matters: Vague principles like "be good" provide less useful signal than specific principles like "avoid providing information that could be used to create weapons." More specific principles give the AI clearer criteria for evaluation. This specificity helps because it reduces the interpretive burden on the evaluator model, making judgments more consistent and reliable. When a principle is too vague, the evaluator must fill in the gaps with its own implicit understanding, which may not align with your intent.

Principles should be actionable: A principle stating what to avoid is more actionable than one stating abstract values. "Choose the response that doesn't include personal insults" is more actionable than "choose the nicer response." Actionable principles translate directly into evaluation criteria, making the comparison task clearer for the AI evaluator. They also make the resulting model behavior more predictable, since the connection between principle and behavior is more direct.

Coverage requires multiple principles: No single principle captures all desired behaviors. Effective constitutions include principles addressing helpfulness, safety, honesty, and other dimensions. During evaluation, different principles can be applied to focus on different aspects. This multi-principle approach ensures that the model receives training signal across all relevant dimensions of quality, rather than optimizing heavily for one dimension at the expense of others.

Ordering affects emphasis: When multiple principles are presented, their ordering can influence which gets prioritized. Important principles should appear early and be emphasized. This ordering effect reflects how language models process sequences: earlier content establishes context that shapes interpretation of later content. You can leverage this effect to communicate relative importance.

A sample constitution might include:

1. Please choose the response that is the most helpful to the human while

being safe and avoiding harmful content.

2. Choose the response that sounds most similar to what a thoughtful,

senior employee at a technology company would say.

3. Choose the response that is most accurate and factual, and that

carefully distinguishes between what it knows and what it doesn't know.

4. Choose the response that best refuses requests for dangerous or

unethical actions while still being helpful within appropriate bounds.

5. Choose the response that is least likely to be perceived as harmful,

toxic, or offensive by a thoughtful person.

Notice how each principle targets a different aspect of quality: general helpfulness and safety, professional tone, factual accuracy and recognizing its limitations, appropriate refusals, and social sensitivity. Together, these principles create a comprehensive framework for evaluating response quality across multiple dimensions.

AI Preference Generation

With constitutional principles in place, the next step is generating preference data at scale. This process requires careful prompt engineering and consideration of potential failure modes. The goal is to produce preference labels that reliably capture the quality distinctions encoded in the constitution, while minimizing noise and systematic biases that could corrupt the training signal.

Prompting Strategies for Preference Collection

The prompt structure significantly affects preference quality. The way we frame the evaluation task influences how the AI interprets its role and applies the constitutional principles. Several strategies improve AI preference reliability:

Pairwise comparison: Present both responses simultaneously and ask which is better. This mirrors human annotation protocols and allows direct comparison. The simultaneous presentation is important because it enables the evaluator to make relative judgments, comparing specific features of each response rather than trying to assess absolute quality. Relative judgments tend to be more reliable because they require less calibration.

Consider these two responses to the question: "{question}"

[Response A]

{response_a}

[Response B]

{response_b}

According to the principle "{principle}", which response is better?

Explain your reasoning briefly, then state your choice as "A" or "B".

Chain-of-thought evaluation: Asking the AI to explain its reasoning before stating a preference often produces more reliable judgments, mirroring the benefits of chain-of-thought reasoning we discussed in earlier chapters. When the model must articulate why one response is better, it engages more deeply with the evaluation criteria and is less likely to make superficial judgments. The reasoning trace also provides useful information for debugging and improving the constitution.

Multiple principles, aggregated: Evaluate response pairs against multiple constitutional principles and aggregate the results. This provides more robust signal than relying on any single principle. Different principles might favor different responses, and aggregation helps identify responses that perform well across multiple dimensions. This approach also provides resilience against any single principle being poorly specified or having unintended consequences.

Position debiasing: AI models can exhibit position bias, preferring whichever response appears first (or last). Running each comparison twice with swapped positions and averaging the results reduces this bias. Position bias is a well-documented phenomenon in language models, likely arising from patterns in training data where the first option in a list is often the default or recommended choice. By running comparisons in both orderings and requiring agreement, we filter out preferences that are driven by position rather than content.

Comparison with Human Preferences

Research has found substantial agreement between AI and human preferences, though the agreement varies by task type. Understanding when AI preferences are reliable and when they diverge from human judgment is essential for designing effective RLAIF systems.

For tasks with clear quality differences (one response is factually wrong, one follows instructions while the other doesn't), AI and human preferences agree strongly, often exceeding 80% agreement. These are cases where the quality signals are salient and unambiguous, making evaluation relatively straightforward for both humans and AI. For nuanced judgments involving style preferences, humor, or subtle harmful content, agreement tends to be lower. These cases require implicit cultural knowledge, personal experience, or sensitivity to context that current models may lack.

Importantly, AI preferences aren't necessarily worse than human preferences, just different. Human annotators disagree with each other at substantial rates (often 20-30% disagreement on borderline cases). AI preferences provide a different but often complementary signal. The systematic nature of AI preferences can be advantageous: while individual humans vary in their standards and attention levels, AI evaluators apply the same criteria consistently across all comparisons.

Research from Google DeepMind on their RLAIF work showed that models trained with AI feedback achieved comparable or sometimes superior performance to those trained with human feedback, particularly on helpfulness metrics. This suggests that for many alignment objectives, AI feedback provides sufficient signal. The key insight is that perfect agreement with human preferences is not necessary for effective training. What matters is that the AI preferences capture enough of the relevant quality distinctions to guide the model toward better behavior.

Handling Uncertainty and Edge Cases

Not all comparisons have clear answers. Effective RLAIF systems need strategies for handling ambiguous cases where neither response is obviously better, or where the appropriate judgment depends on factors not captured in the comparison. Forcing judgments on ambiguous cases introduces noise into the training signal and may teach the reward model spurious correlations.

Confidence calibration: Ask the AI not just for a preference but for a confidence level. Low-confidence judgments can be excluded from training or given lower weight. This approach recognizes that not all preference labels are equally reliable. By incorporating confidence into the training process, we can weight the loss function to emphasize high-confidence comparisons where the signal is cleaner.

Abstention: Allow the AI to indicate that two responses are roughly equal quality, rather than forcing a choice. Ties can be excluded from reward model training. This approach is particularly valuable for cases where both responses are acceptable and the differences come down to stylistic preferences that shouldn't be optimized strongly.

Ensemble evaluation: Use multiple AI evaluators (different prompts, different models) and only include comparisons where evaluators agree. This ensemble approach provides additional robustness by requiring consensus before accepting a preference label. Disagreement among evaluators signals ambiguity that should not contribute to training.

The helpful, detailed response is selected over the terse one, demonstrating how even a simple simulation captures basic quality differences that would inform reward model training.

Implementing RLAIF

Let's build a more complete RLAIF implementation that demonstrates the full pipeline from AI preference generation through reward model training. This implementation will illustrate how the theoretical concepts we've discussed translate into working code.

The implementation proceeds in three stages. First, we define the constitutional principles that will guide evaluation. Second, we build a preference generator that applies these principles with appropriate debiasing techniques. Third, we train a reward model on the resulting preference data using the Bradley-Terry framework familiar from our RLHF chapters.

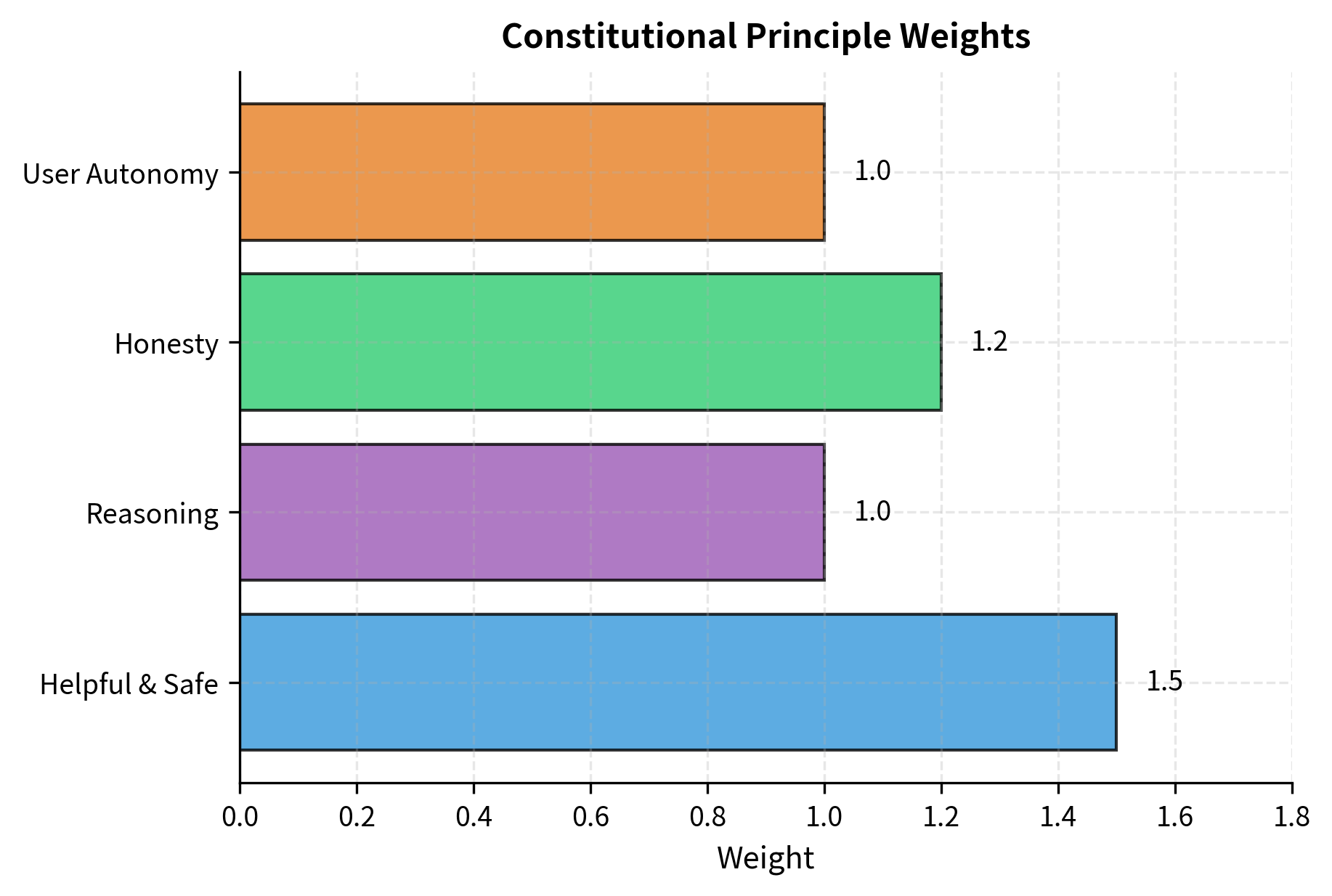

The constitution object now holds our weighted principles and can generate prompts that guide the LLM's evaluation. Notice how each principle receives a weight that reflects its relative importance. The helpfulness and safety principle receives the highest weight (1.5), followed by honesty (1.2), with reasoning quality and user autonomy at the base weight (1.0). These weights will influence how votes from different principles are aggregated.

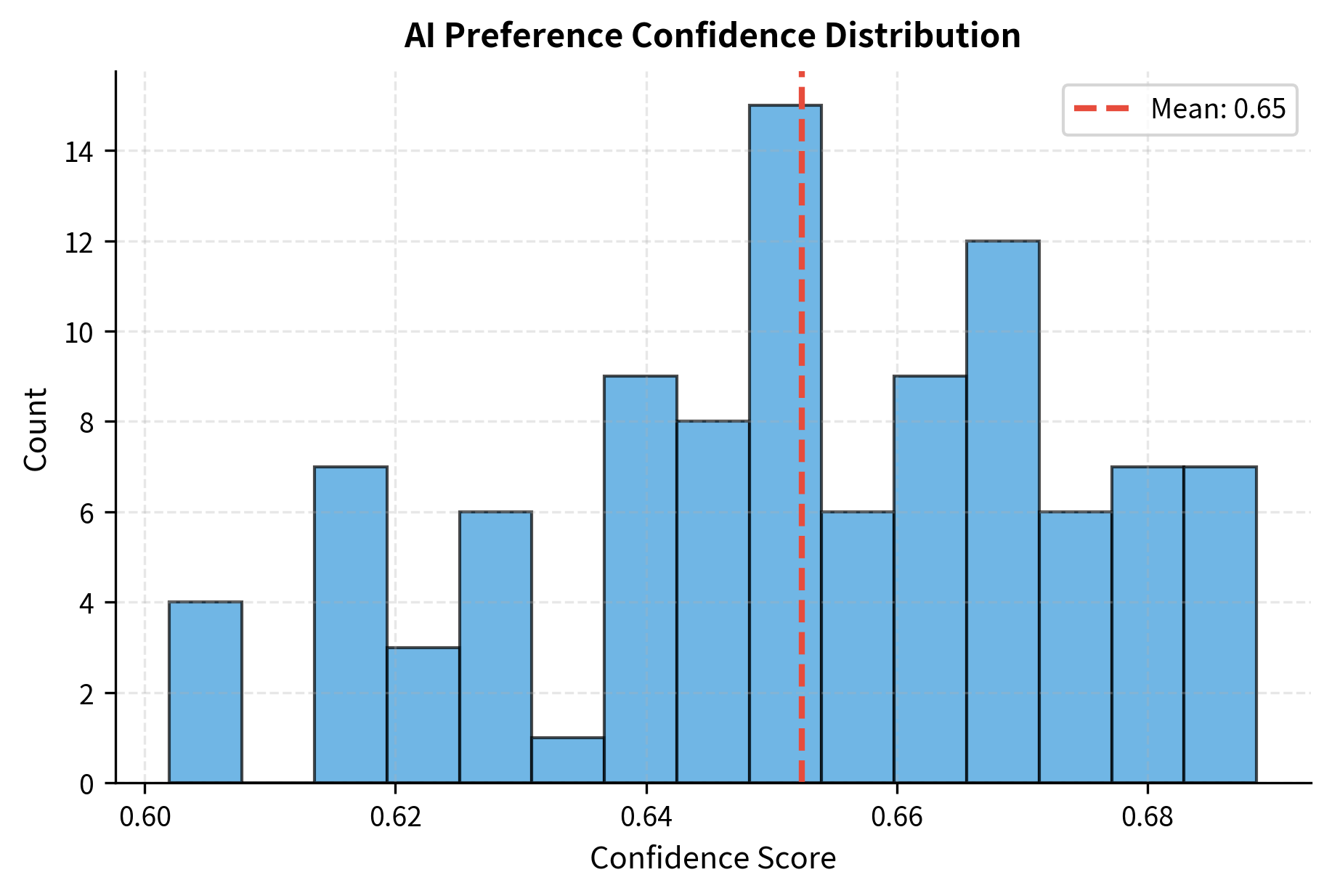

Now let's implement the preference generation system with position debiasing. The preference generator is the core component that transforms constitutional principles into actionable preference labels. It applies multiple principles, runs comparisons in both orderings to detect position bias, and aggregates results to produce reliable labels with associated confidence scores.

The generator produces preferences with confidence scores, abstaining when the signal is weak or inconsistent. In the first test case, the detailed explanation is strongly preferred over the dismissive one-liner. The second test case presents a closer comparison, where both responses are reasonable but differ in their level of explanation and justification.

Now let's implement a reward model that can be trained on these AI-generated preferences. The reward model architecture follows the same principles we established in our RLHF chapters: it takes a prompt-response pair as input and outputs a scalar reward score. The key difference is that our training signal now comes from AI-generated preference labels rather than human annotations.

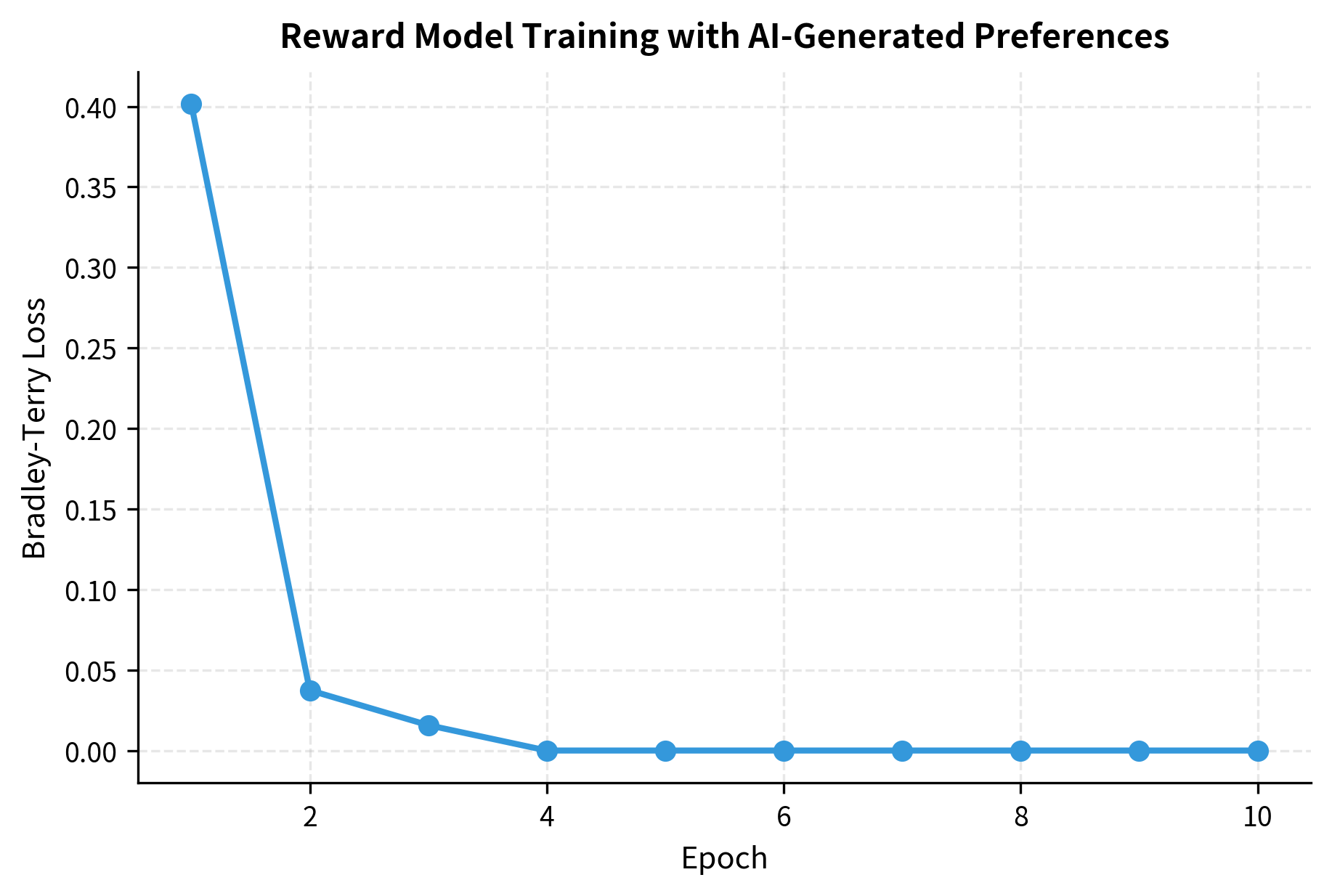

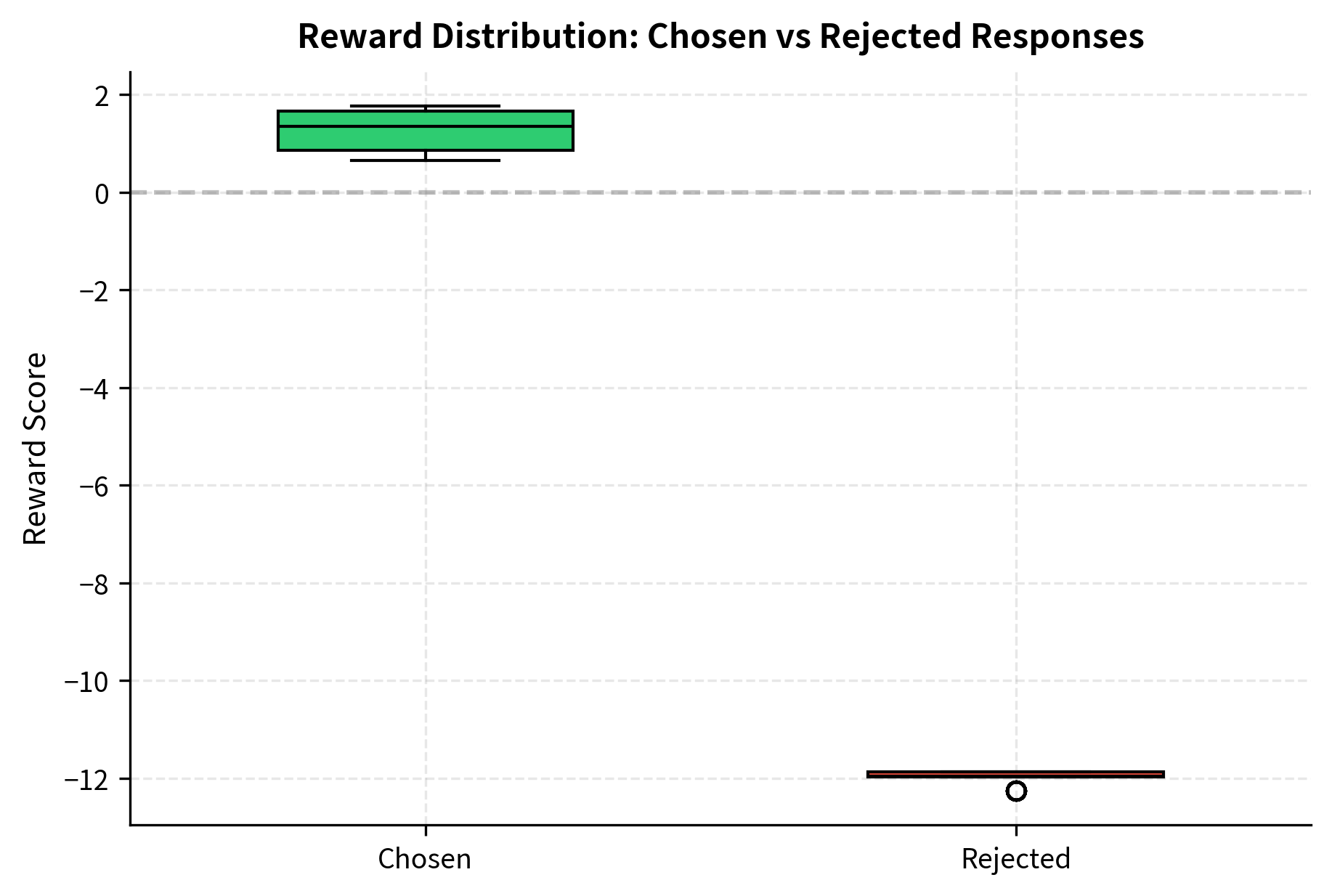

The reward model uses a bidirectional LSTM to encode the input sequence, then applies a two-layer feedforward network to produce the final reward score. We use the Bradley-Terry loss, which maximizes the probability that the chosen response receives a higher reward than the rejected response. The loss is weighted by the confidence from the AI preference generator, so high-confidence labels contribute more to the gradient.

The final loss value confirms that the model has converged on the preference data. Starting from random initialization, the reward model has learned to assign higher rewards to the responses that the AI preference generator marked as chosen.

The decreasing loss indicates the reward model is learning to distinguish between preferred and rejected responses based on the AI-generated labels. The smooth descent suggests stable training, and the final loss level indicates that the model has successfully captured the quality distinctions present in the preference data.

Key Parameters

The key parameters for the Reward Model implementation are:

- vocab_size: The size of the vocabulary for the embedding layer. This determines how many unique tokens the model can represent. In practice, this matches the tokenizer's vocabulary size.

- embed_dim: The dimensionality of the word embeddings. Higher values allow richer representations but increase computational cost. Typical values range from 64 to 768.

- hidden_dim: The number of features in the hidden state of the LSTM. This controls the capacity of the encoder to capture sequential patterns. Since we use a bidirectional LSTM, the final representation has dimension 2 × hidden_dim.

- epochs: The number of full passes through the training dataset. More epochs allow for better convergence but risk overfitting, especially with small datasets.

- lr: The learning rate for the Adam optimizer. This controls how quickly the model updates its parameters. Values between 1e-4 and 1e-3 are common starting points.

- batch_size: The number of training samples processed before updating the model parameters. Larger batches provide more stable gradients but require more memory.

RLAIF Scalability

The main advantage of RLAIF is its scalability. Let's examine the concrete differences between human and AI annotation at scale.

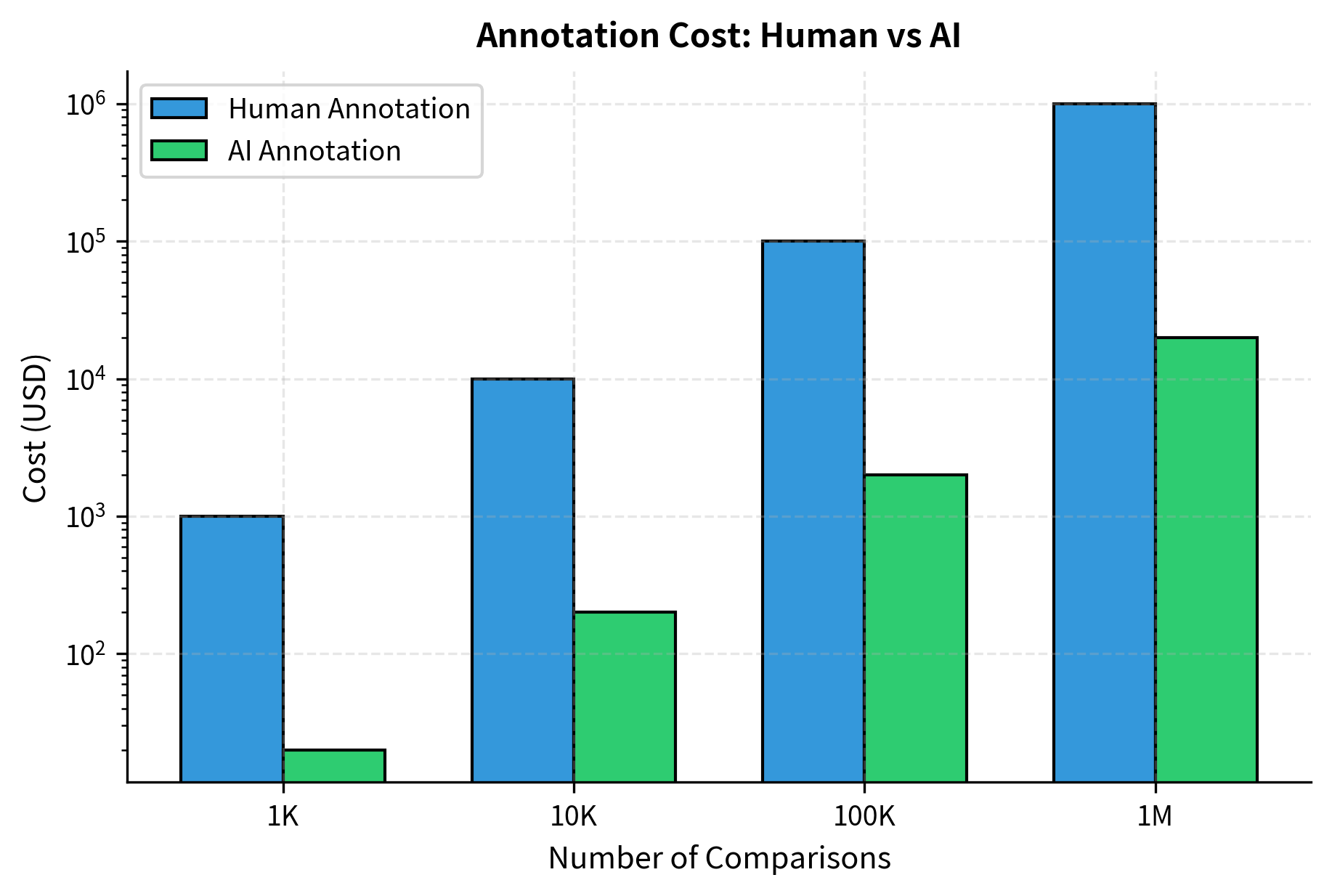

Cost Analysis

Human annotation costs scale linearly with data volume. A typical preference annotation task might cost $0.50-$2.00 per comparison when accounting for annotator wages, quality control, and platform fees. Collecting 100,000 preference pairs, a moderate dataset size, costs $50,000-$200,000 in human annotation alone.

AI annotation using API calls costs dramatically less. Using a capable model like GPT-4 or Claude, generating a preference judgment might cost $0.01-$0.05 per comparison (depending on response lengths and model pricing). The same 100,000 comparisons would cost $1,000-$5,000, a reduction of 1-2 orders of magnitude.

With self-hosted models, costs drop further. Running inference on your own hardware reduces the per-comparison cost to near zero, limited only by compute time. This enables generating millions of preference pairs for the cost of GPU hours.

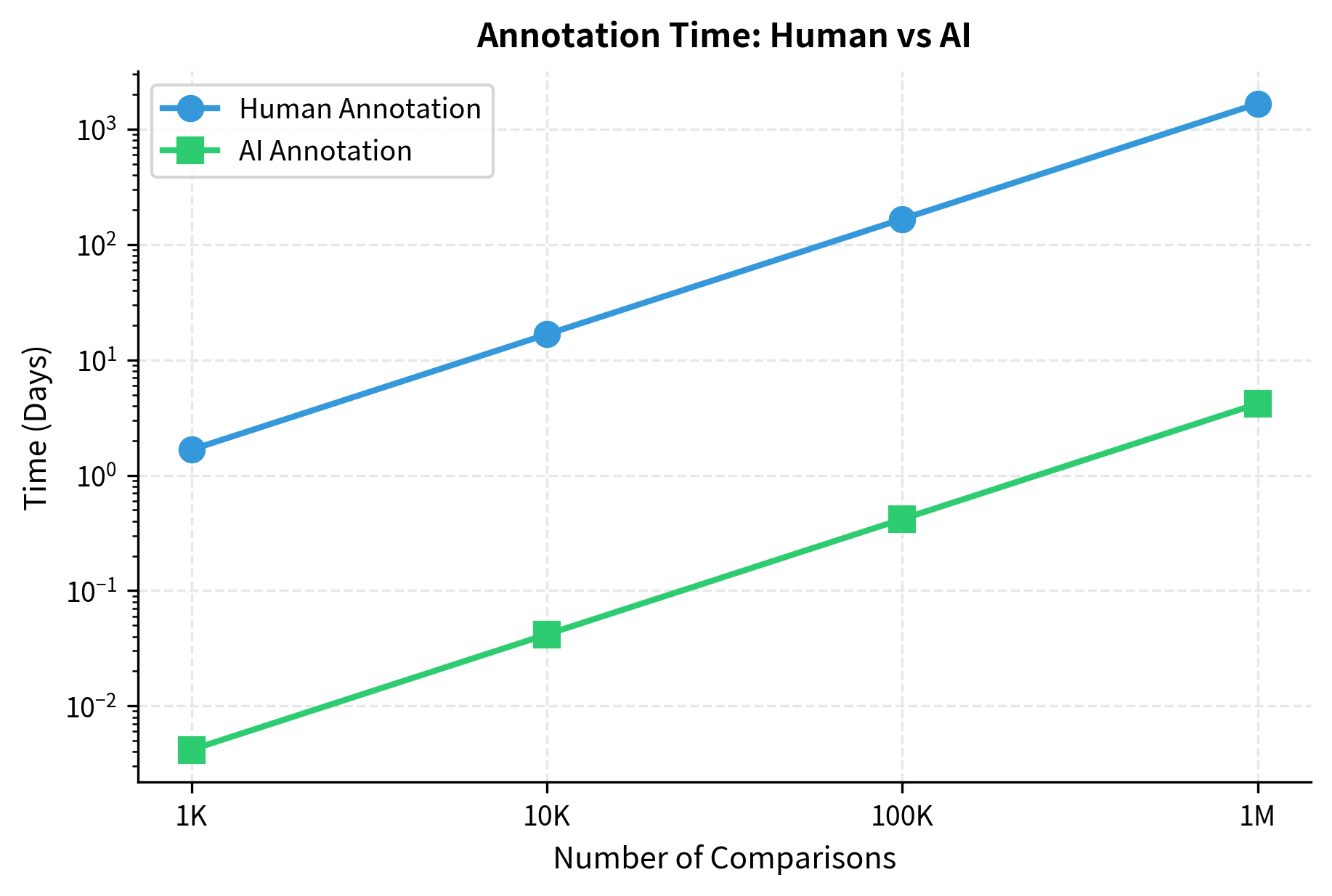

Speed Analysis

Human annotation throughput is limited by human reading and decision speed. A skilled annotator might complete 50-100 preference comparisons per hour. Collecting 100,000 comparisons requires approximately 1,000-2,000 annotator-hours.

AI annotation is easy to parallelize. A single API endpoint can handle thousands of requests per minute. Self-hosted inference on multiple GPUs can generate tens of thousands of preference labels per hour. The same 100,000 comparisons might take hours rather than weeks.

At one million comparisons, the difference becomes stark: human annotation would cost a million dollars and take over 18 months of continuous work (assuming a single annotator), while AI annotation costs $20,000 and completes in about four days.

Iterative Improvement at Scale

RLAIF's scalability enables fundamentally different alignment workflows. With human annotation, iteration is expensive: each training run requires a new round of costly data collection. You might run 2-3 iterations before budget constraints force you to ship.

With RLAIF, you can iterate rapidly. Generate a million preferences, train, evaluate, refine the constitution, and repeat. This rapid iteration allows for:

- Constitution refinement: Test different principles and measure their impact on model behavior

- Data diversity: Generate preferences across a much broader distribution of prompts and response types

- Continuous improvement: Update alignment as models improve or requirements change

The next chapter on Iterative Alignment explores how this scalability enables continuous refinement of model behavior through multiple rounds of RLAIF.

Limitations and Challenges

Despite its advantages, RLAIF faces significant challenges that limit its applicability.

The "Model-As-Judge" Problem

When an AI model evaluates responses, it brings its own biases and limitations. A model trained on internet text might prefer verbose, confident-sounding responses even when brevity or uncertainty would be more appropriate. It might miss subtle harmful content that requires real-world knowledge or cultural context that humans would catch.

This creates a concerning circularity: we're using AI to generate training signal for AI. If the evaluator model has systematic biases, those biases propagate into the trained model. Unlike human annotation, where diverse annotators might average out individual biases, AI evaluation can amplify consistent model biases.

Research has documented several specific biases in AI evaluation. Models tend to prefer longer responses, prefer responses that use technical jargon, and show position bias (preferring whichever response appears first or last). Careful prompt engineering and debiasing techniques can mitigate but not eliminate these issues.

Constitutional Completeness

No constitution can anticipate every scenario a model will encounter. Writing a constitution requires foreseeing failure modes, but novel harmful behaviors emerge from unexpected interactions between capabilities and user requests. A constitution that addresses known harms may miss new categories of misuse.

Furthermore, constitutional principles can conflict. "Be helpful" and "avoid harm" often conflict with each other. "Be honest" might conflict with "respect privacy." The constitution itself cannot resolve these conflicts; it can only provide heuristics that the AI applies with its own judgment. This means alignment quality depends partly on the evaluator model's ability to balance competing principles, a capability that varies across models and scenarios.

The Distributional Gap

The AI evaluator was trained on a particular distribution of text. When asked to evaluate responses far from that distribution, for instance novel technical domains, minority cultural contexts, or unusual linguistic registers, its judgments become less reliable. Humans, despite their own limitations, can draw on personal experience and common sense that current models lack.

This distributional gap matters most for high-stakes decisions. For routine helpfulness comparisons, AI judgment often suffices. For nuanced judgments about potentially harmful content in specialized domains, human oversight remains valuable.

When to Prefer Human Feedback

RLAIF doesn't replace human feedback entirely. Instead, it's most effective as a complement:

- Use RLAIF for: High-volume data generation, clear-cut comparisons, initial training phases, rapid iteration

- Use human feedback for: Edge cases, high-stakes decisions, novel scenarios, calibrating AI evaluators, final quality assurance

A practical approach uses RLAIF for the majority of training data while reserving human annotation budget for difficult cases and validation. This hybrid approach captures the scalability of AI annotation while maintaining human oversight where it matters most.

Summary

RLAIF replaces human annotators with AI systems that evaluate response quality and generate preference data. This substitution maintains the core RLHF training pipeline while dramatically improving scalability.

Constitutional AI provides the principled framework that makes RLAIF effective. By grounding AI judgments in explicit, written principles rather than implicit preferences, CAI makes the alignment target auditable and consistent. The two-phase CAI process uses critique-and-revision for supervised data generation and constitutional preference labels for reinforcement learning.

Generating high-quality AI preferences requires careful attention to prompt engineering. Position debiasing, chain-of-thought evaluation, and principle aggregation all improve preference reliability. Confidence calibration and abstention mechanisms help filter low-quality judgments.

The scalability advantages of RLAIF are substantial. Costs drop by 1-2 orders of magnitude compared to human annotation, and throughput increases by 2-3 orders of magnitude. This enables rapid iteration, broad coverage, and continuous improvement in ways that human-only annotation cannot support.

However, RLAIF has significant limitations. AI evaluators carry their own biases, constitutions cannot cover all scenarios, and distributional gaps limit AI judgment quality in unfamiliar domains. The most effective approach combines RLAIF's scalability with targeted human oversight, using AI annotation for volume while reserving human judgment for edge cases and validation.

Quiz

Ready to test your understanding? Take this quick quiz to reinforce what you've learned about Reinforcement Learning from AI Feedback and Constitutional AI.

Comments