Learn few-shot fine-tuning techniques for language models. Master PET, SetFit, and data augmentation to achieve strong results with limited labeled data.

This article is part of the free-to-read Language AI Handbook

Choose your expertise level to adjust how many terms are explained. Beginners see more tooltips, experts see fewer to maintain reading flow. Hover over underlined terms for instant definitions.

Fine-tuning Data Efficiency

One of the most remarkable properties of pre-trained language models is their ability to adapt to new tasks with surprisingly few examples. Where traditional machine learning often requires thousands or millions of labeled samples, a pre-trained transformer can achieve strong performance with just dozens or hundreds. This chapter explores the techniques and strategies that enable this data efficiency, from few-shot fine-tuning methods to data augmentation approaches designed specifically for text.

Understanding data efficiency is crucial for practical applications. Most real-world NLP problems don't come with massive labeled datasets. Medical text classification might have only a few hundred expert-annotated examples. A new product category might have just a handful of customer reviews. Legal document analysis often relies on expensive attorney annotations. The ability to achieve good performance with limited data isn't just a nice property; it's often the difference between a viable project and an impossible one.

The Sample Efficiency Spectrum

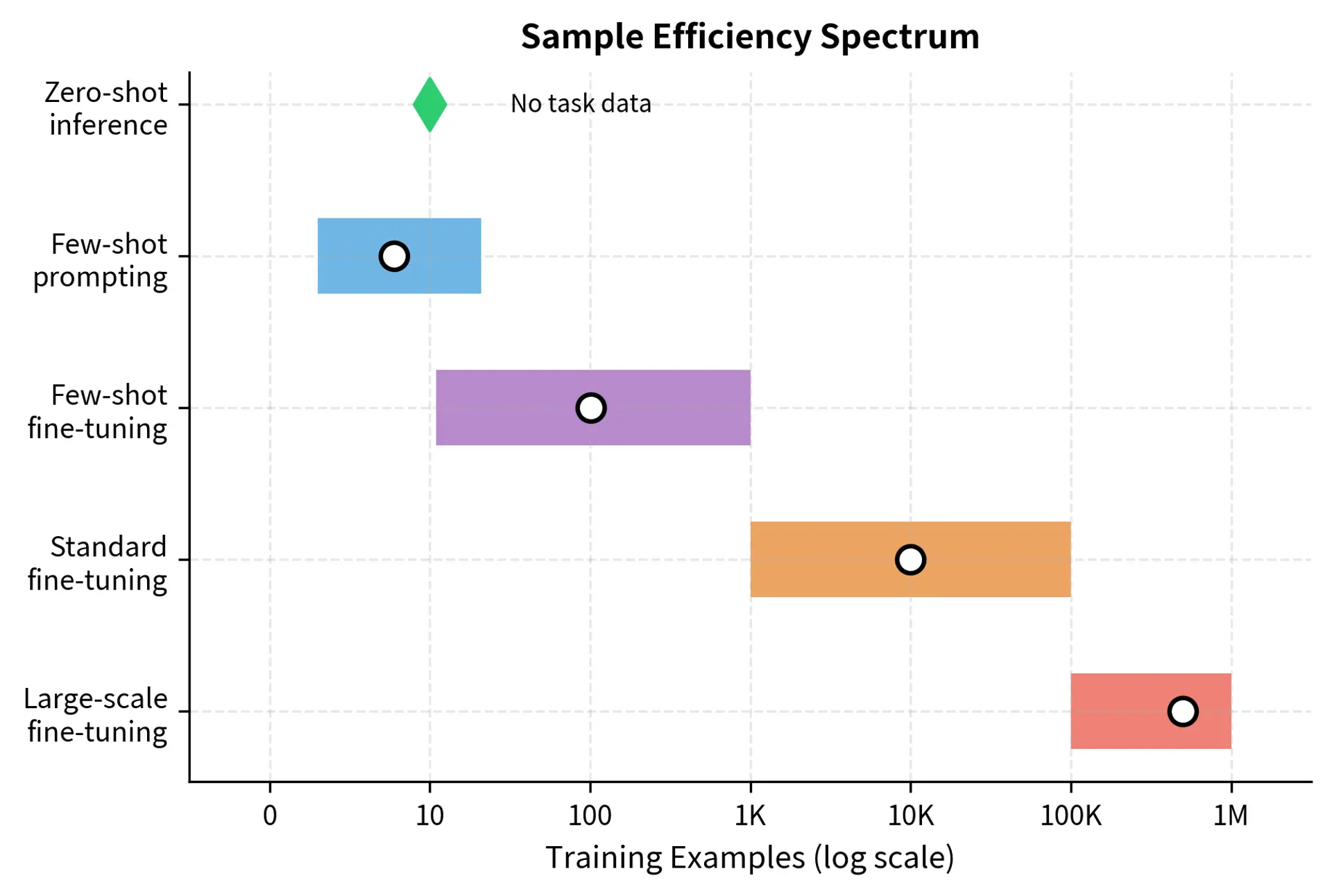

Data efficiency in language AI spans a wide spectrum, from tasks requiring no task-specific data at all to those benefiting from millions of examples. Understanding where your problem falls on this spectrum helps you choose the right approach and set realistic expectations for what can be achieved with your available resources.

Zero-shot inference uses the model's pre-trained capabilities without any task-specific fine-tuning. As we saw with GPT-3's in-context learning in Part XVIII, large language models can perform many tasks simply through careful prompting. The model generalizes from its pre-training data to new tasks, drawing on the vast knowledge encoded in its parameters during the initial training phase.

Few-shot prompting provides a handful of examples in the prompt itself, guiding the model's behavior without updating any weights. This approach works well for tasks similar to what the model encountered during pre-training but doesn't create a specialized model. The examples serve as demonstrations that help the model understand the desired input-output relationship.

Few-shot fine-tuning updates model weights using a small labeled dataset, typically 10 to 1,000 examples. This creates a specialized model that often outperforms few-shot prompting, especially for tasks that differ significantly from pre-training. By actually modifying the model's parameters, few-shot fine-tuning creates a more permanent adaptation than prompt-based approaches.

Standard fine-tuning uses moderate amounts of data, typically 1,000 to 100,000 examples. This is the regime where most practical fine-tuning occurs, balancing data collection costs against model performance. At this scale, practitioners can expect reliable, reproducible results with lower variance across training runs.

Large-scale fine-tuning applies when you have hundreds of thousands or millions of labeled examples. At this scale, even smaller pre-trained models can achieve excellent results, and the benefits of larger pre-trained models diminish relative to smaller ones. The abundance of task-specific data can compensate for less sophisticated pre-training.

The key insight is that pre-training fundamentally changes the relationship between data quantity and model performance. A pre-trained BERT fine-tuned on 100 examples often outperforms a randomly initialized model trained on 10,000 examples. The representations learned during pre-training provide such strong priors that far less task-specific data is needed. This shift in the learning curve represents one of the most significant practical advances in modern NLP.

Few-Shot Fine-Tuning

Few-shot fine-tuning adapts a pre-trained model using only a handful of labeled examples per class. This setting is particularly challenging because small datasets are prone to overfitting, and variance across different training runs can be high. The fundamental tension in few-shot learning lies between extracting maximum information from limited examples while avoiding the trap of memorizing noise or spurious patterns.

Pattern-Exploiting Training

Pattern-Exploiting Training (PET) reformulates classification tasks as cloze-style fill-in-the-blank problems that match the pre-training objective. Instead of training a separate classification head, PET leverages the model's masked language modeling capability. This approach is clever because it reuses exactly the skill the model developed during pre-training, rather than asking it to learn an entirely new type of prediction.

Consider sentiment classification. Rather than adding a classification layer that must learn from scratch how to map hidden states to class probabilities, PET transforms the input into a format the model already understands:

Input: "This movie was terrible."

Pattern: "This movie was terrible. It was [MASK]."

Verbalizer: positive → "great", negative → "bad"

The model predicts probabilities for tokens in the mask position. We map specific tokens (verbalizers) to class labels. Since the model was pre-trained on exactly this kind of task, it can make reasonable predictions even with very few examples. The model already knows that after describing something as "terrible," the word "bad" is more likely than "great" in the masked position, giving it a strong prior even before seeing any task-specific training data.

The pattern design significantly impacts performance because it determines how well the classification task aligns with what the model learned during pre-training. Effective patterns share several characteristics:

- They sound natural and fluent, resembling text the model would have encountered during pre-training.

- They match the pre-training distribution, using constructions common in the training corpus.

- They place the mask in a semantically meaningful position where the predicted word genuinely indicates the class.

- They use verbalizers that clearly distinguish classes, selecting words whose meanings unambiguously correspond to each label.

SetFit: Contrastive Few-Shot Learning

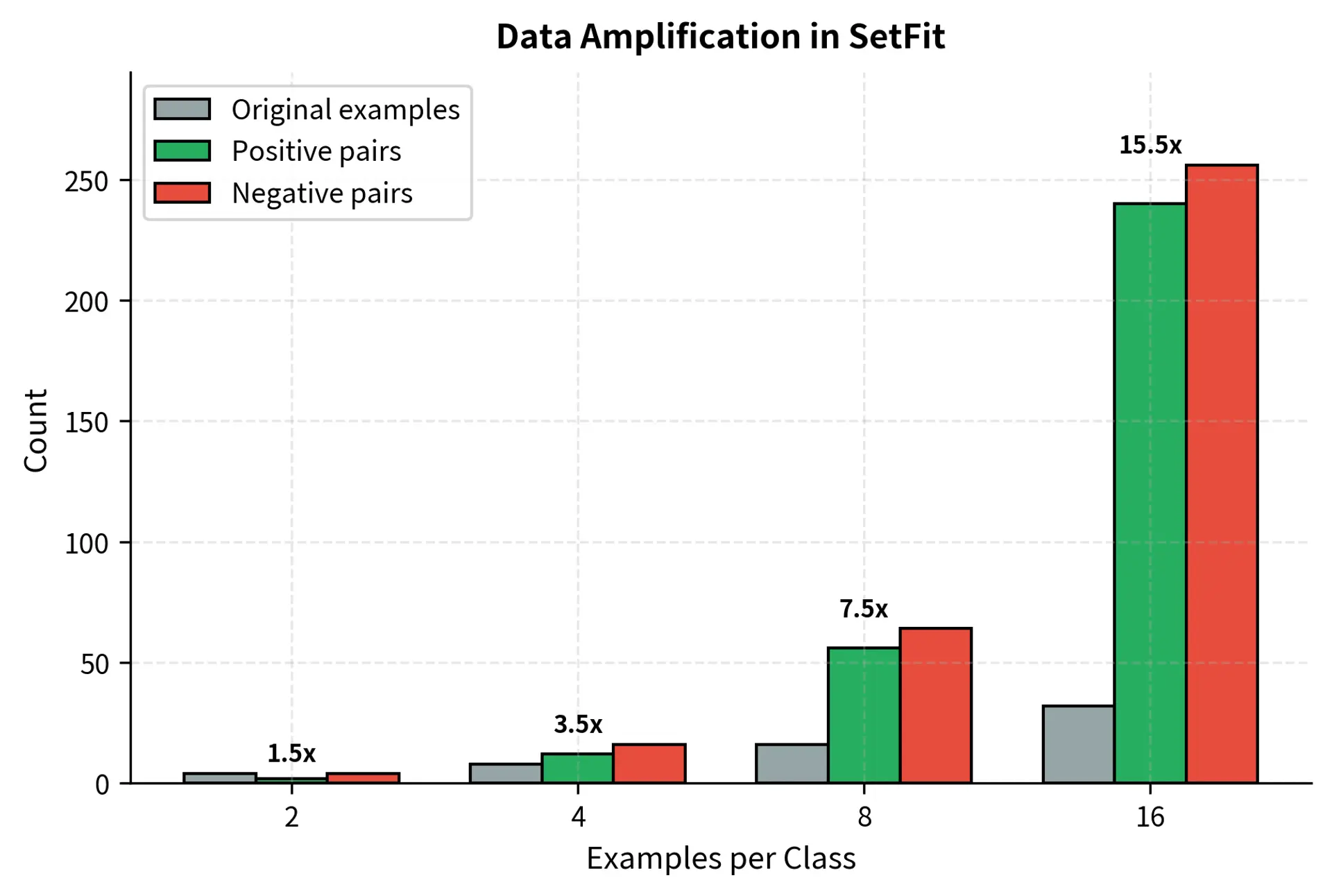

SetFit (Sentence Transformer Fine-tuning) takes a different approach, using contrastive learning to maximize data efficiency. Rather than reformulating the task to match pre-training, SetFit amplifies the available training signal through strategic pair generation. The method works in two stages that together transform a small set of labeled examples into a much richer training signal.

Stage 1: Contrastive fine-tuning. Generate pairs of examples from the few-shot dataset. Pairs with the same label are positive pairs; pairs with different labels are negative pairs. Fine-tune a sentence transformer to produce similar embeddings for positive pairs and dissimilar embeddings for negative pairs. This stage teaches the model which examples should be grouped together in the embedding space.

Stage 2: Classification head training. Use the fine-tuned sentence transformer to embed all training examples. Train a simple classifier (logistic regression or small neural network) on these embeddings. Because the embeddings now cluster by class, even a simple classifier can achieve strong performance.

SetFit's power comes from data amplification through pairing. With examples per class and classes, you can generate positive pairs and many more negative pairs. Even 8 examples per class yields hundreds of training pairs for the contrastive objective. This combinatorial explosion transforms a seemingly inadequate training set into one rich enough for meaningful learning.

Stability in Few-Shot Settings

Few-shot fine-tuning exhibits high variance across runs, which represents one of its most challenging aspects. Different random seeds for weight initialization, data ordering, or the specific examples selected can dramatically change results. A model that achieves 90% accuracy in one training run might only reach 70% in another, even with identical hyperparameters. Several techniques improve stability and make results more reliable.

Multiple random restarts train the model multiple times with different seeds and either ensemble the predictions or select the best model based on a small validation set. This reduces the risk of unlucky initialization and provides a more representative picture of achievable performance.

Training set sampling creates multiple few-shot subsets from a larger pool. If you have 100 labeled examples but want to simulate 10-shot learning, create multiple 10-shot subsets and train on each. This helps identify robust patterns that persist across different example selections rather than patterns specific to one particular subset.

Gradual unfreezing starts by training only the classification head, then progressively unfreezes deeper layers. This prevents early training instability from corrupting pre-trained representations. By allowing the classification head to stabilize before introducing changes to earlier layers, the model maintains the valuable features learned during pre-training.

As we discussed in the previous chapter on fine-tuning learning rates, using lower learning rates is particularly important in few-shot settings. The limited data provides weak gradient signals, so aggressive updates can quickly overwrite useful pre-trained knowledge. A learning rate that works well with 10,000 examples might be catastrophically high with 100 examples.

Data Augmentation for NLP

Data augmentation artificially expands the training set by creating modified versions of existing examples. While augmentation has been transformative for computer vision (random crops, rotations, color changes), text augmentation is more challenging because small changes can alter meaning dramatically. Changing a single word can flip the sentiment of a sentence, and rearranging phrases can make text ungrammatical. The goal is to introduce meaningful variation while preserving the label's validity.

Synonym Replacement

The simplest augmentation replaces words with synonyms:

Original: "The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog."

Augmented: "The fast brown fox leaps over the lazy dog."

This preserves the overall meaning while introducing lexical variation. The model learns that both "quick" and "fast," or "jumps" and "leaps," can express similar concepts, reducing its dependence on specific vocabulary. However, synonym replacement has limitations: not all words have good synonyms, context matters (a "bank" isn't always replaceable with "shore"), and some domains have specialized vocabulary where synonyms don't exist.

Back-Translation

Back-translation generates paraphrases by translating text to another language and back:

Original (English): "I love this product"

→ German: "Ich liebe dieses Produkt"

→ English: "I love this product" or "I adore this item"

The translation process naturally introduces variation in word choice and sentence structure while typically preserving meaning. Each translation step makes decisions about how to express concepts, and these decisions may differ from the original phrasing. Using multiple intermediate languages generates more diverse paraphrases, as each language brings its own structural biases and vocabulary choices to the translation process.

Random Operations

Several random operations can augment text data, each providing different types of robustness.

Random insertion adds random words from the vocabulary into sentences. While this might seem likely to introduce noise, it encourages the model to focus on key words rather than word order. The model learns to identify important content words even when surrounded by distractors.

Random swap exchanges the positions of two words in a sentence. Again, this seems potentially harmful, but it helps models become robust to minor ordering variations. Many classification tasks don't depend on exact word order, and this augmentation reflects that reality.

Random deletion removes words with some probability. This simulates incomplete or noisy input and prevents over-reliance on specific words. If a model can still classify correctly with some words missing, it has learned more robust patterns than one requiring all words present.

These random operations work best when applied conservatively. Augmenting too aggressively can create examples that are too different from real data, training the model on a distribution that doesn't match what it will encounter at test time.

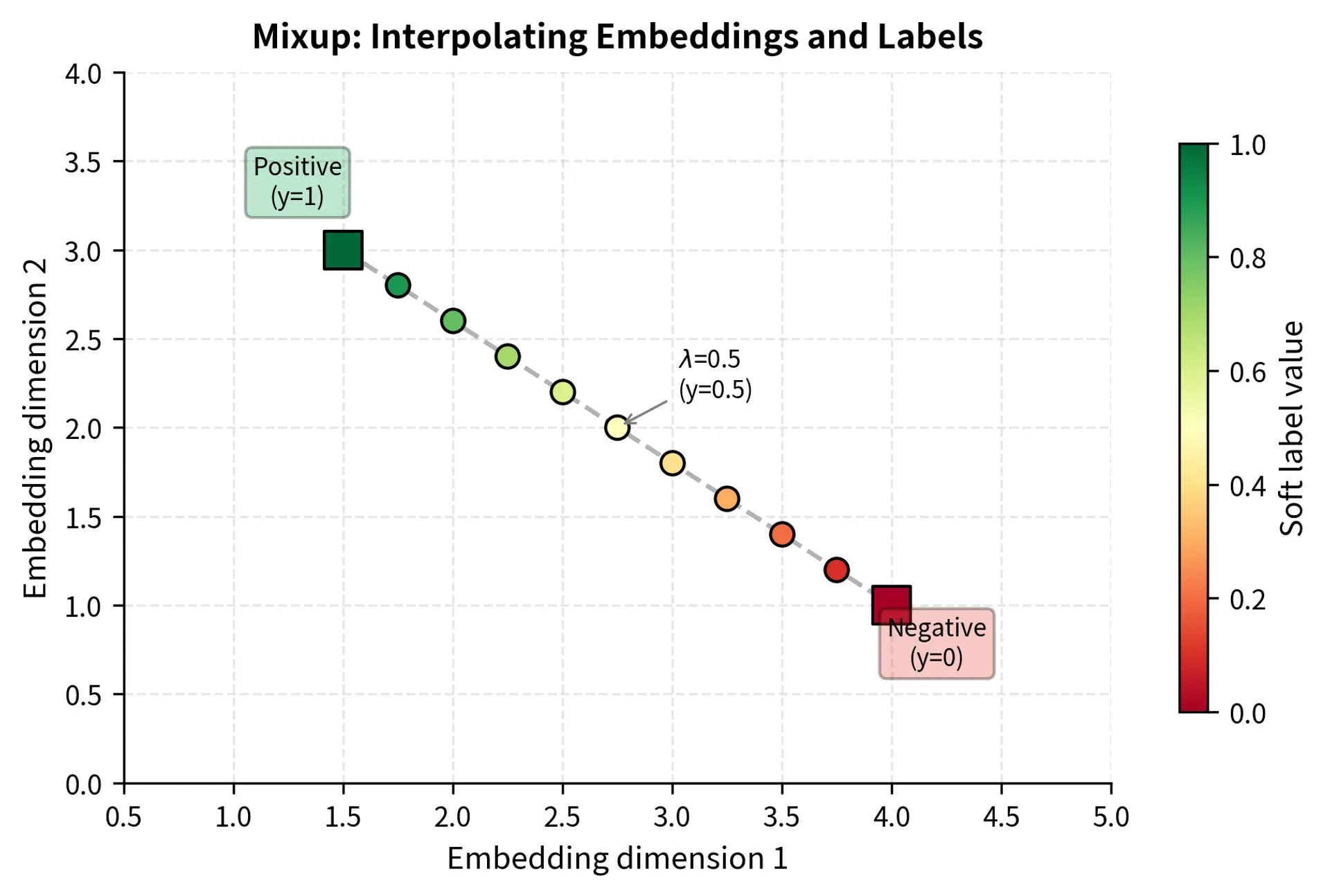

Mixup for Text

Mixup, originally developed for images, creates new training examples by interpolating between existing ones. The intuition behind mixup is simple but powerful: by training on blended examples with soft labels, we encourage the model to behave linearly in the space between training points, leading to smoother decision boundaries. For text, this is less straightforward since we can't meaningfully interpolate discrete tokens. You cannot average the word "happy" and "sad" to get a word that is half-positive. Instead, text mixup operates in embedding space, where continuous representations make interpolation meaningful:

Given two examples and , we create a synthetic example by interpolating their embeddings and labels:

where:

- : the embedding vector for the new synthetic example

- : the label for the new example (a "soft" target)

- : the mixing coefficient sampled from a Beta distribution (), controlling the ratio between the two examples

- : the embeddings of the original examples (typically [CLS] token embeddings or pooled representations)

- : the labels of the original examples

The first equation creates a new embedding that lies somewhere on the line segment connecting the two original embeddings in the high-dimensional space. When , we recover the first example exactly; when , we recover the second. Intermediate values produce embeddings that blend characteristics of both inputs.

The second equation applies the same interpolation to the labels. This is what makes mixup so distinctive: rather than assigning a hard label to the synthetic example, we assign a soft target that reflects the mixture. This process smooths the decision boundary in the embedding space by teaching the model that intermediate regions should have intermediate predictions. For instance, if a positive example () is mixed with a negative example () with , the target label becomes , encouraging the model to reflect this ambiguity in its prediction confidence. The model learns that it should be more confident near pure examples and less confident in the interpolated regions between classes.

The Beta distribution for sampling is chosen because it naturally produces values between 0 and 1, and its shape parameter controls how often extreme values (near 0 or 1) versus moderate values (near 0.5) are sampled. Lower shape parameters favor interpolations closer to the original examples, while higher values encourage more balanced mixing.

Contextual Augmentation

More sophisticated augmentation uses language models themselves to generate variations. Given a sentence, mask out one or more words and use a masked language model to predict replacements:

Original: "The movie was incredibly boring."

Masked: "The movie was incredibly [MASK]."

Augmented: "The movie was incredibly dull." (from MLM prediction)

This approach generates contextually appropriate substitutions that maintain grammaticality better than random synonym replacement. The language model considers the full context when selecting a replacement word, ensuring that the augmented word fits naturally in its surroundings. A word like "dull" is chosen because the model has learned that it appears in similar contexts to "boring."

Generative models can create even more diverse augmentations. Given a few examples of a class, a language model can generate entirely new examples in the same style, potentially multiplying the effective dataset size many times over. This approach can create examples that express the same sentiment or class membership through entirely different phrasings, providing richer training signal than modifications of existing examples.

Sample Efficiency Patterns

Why are pre-trained models so sample-efficient? Several interconnected factors contribute to this remarkable property, each building on the others to create models that can learn from minimal supervision.

Informative Priors from Pre-training

Pre-training encodes massive amounts of linguistic knowledge into model weights. The model learns syntax, semantics, factual knowledge, and reasoning patterns from billions of tokens of text. This knowledge acts as a strong prior that guides learning on new tasks. Rather than starting from a blank slate, the model begins with rich expectations about how language works.

Consider a sentiment classifier. A randomly initialized model must learn from scratch that "excellent" is positive and "terrible" is negative. It has no prior knowledge connecting these words to positive or negative sentiments. A pre-trained model already knows these associations from context. During pre-training, the model observed sentences like "The excellent performance earned applause" and "The terrible weather ruined the picnic," learning that "excellent" typically appears in positive contexts and "terrible" in negative ones. Fine-tuning merely teaches the model how to apply this existing knowledge to the classification format, connecting what it already knows to the specific output structure required.

Feature Reuse

As we discussed in Part XXIV on transfer learning, pre-trained representations are highly reusable across different tasks. Lower layers encode general linguistic patterns like part-of-speech and syntax. These foundational features are useful for virtually any language task. Middle layers capture phrase-level semantics, understanding how words combine to form meaningful units. Upper layers represent more task-relevant features that can be adapted to specific applications.

When fine-tuning on limited data, most of these features remain useful. The model doesn't need to learn basic language understanding from scratch; it only needs to learn task-specific adjustments on top of already-good representations. This is analogous to how a trained musician learning a new instrument doesn't need to relearn music theory or rhythm. They already possess foundational knowledge that transfers, and only need to learn the specifics of the new instrument.

Label Smoothing Effects

Pre-training also provides implicit regularization that helps prevent overfitting in few-shot settings. The representations aren't perfectly aligned with the downstream task, which acts like noise injection. This imperfect alignment prevents the model from immediately memorizing the few training examples, forcing it to find more general patterns.

Additionally, the pre-trained classification token ([CLS] in BERT) isn't specialized for any particular task. This "neutral initialization" means the model must learn genuine class distinctions rather than exploiting spurious correlations that happen to align with the initialization. If the CLS token were initialized to produce outputs that accidentally correlated with the training labels, the model might find shortcuts rather than learning meaningful features. The neutral initialization ensures the model must earn its performance through genuine learning.

Implementation

Let's implement several data efficiency techniques, starting with data augmentation.

Now let's implement the basic augmentation techniques.

Let's see these augmentation techniques in action.

These examples demonstrate how each technique modifies the input. Synonym replacement and random insertion introduce lexical variety, while random swap and deletion force the model to be robust to noise and structural changes. Note that while meaning is largely preserved, some fluency is lost, which is a trade-off in text augmentation.

Now let's implement a complete augmentation pipeline that combines these techniques.

Let's augment our small training set and see the expansion.

The dataset size has expanded by a factor of four, providing significantly more training signal. The examples show that the augmented versions retain the core sentiment of the original ("positive" or "negative") while introducing variations in phrasing, which helps prevent overfitting to specific words.

Implementing SetFit-Style Training

Now let's implement the core idea behind SetFit: generating contrastive pairs from few-shot data.

This demonstrates how few-shot data can be amplified. From just 8 examples (4 per class), we generated many training pairs for contrastive learning.

Few-Shot Fine-Tuning with Sentence Transformers

Let's implement few-shot fine-tuning using the SetFit approach with a pre-trained sentence transformer.

First, let's see how well the pre-trained embeddings work without any fine-tuning.

The baseline performance demonstrates that pre-trained sentence embeddings capture significant semantic information even without task-specific tuning. Achieving accuracy well above random guessing (50%) with just 8 examples confirms the value of transfer learning.

Now let's compare with augmented training data.

Data augmentation typically yields a performance improvement by helping the model generalize from the limited examples. By seeing variations in phrasing and word choice, the classifier becomes less reliant on specific keywords and more focused on the underlying sentiment.

Contrastive Fine-Tuning Implementation

For a more sophisticated approach, let's implement contrastive fine-tuning on the sentence embeddings.

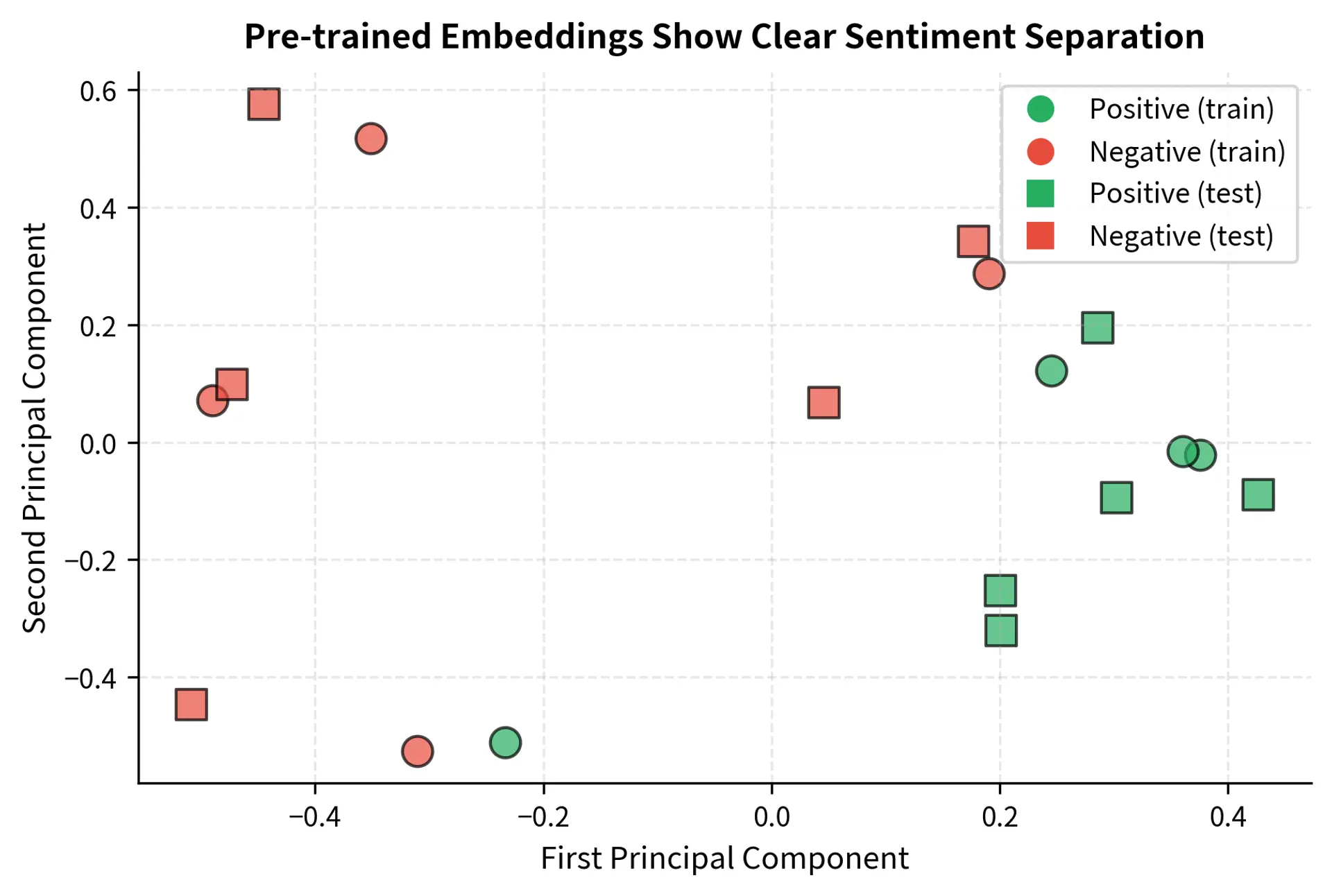

Let's visualize how the embeddings cluster before any task-specific training.

The visualization shows that pre-trained sentence embeddings already capture sentiment distinctions. The positive and negative examples form relatively distinct clusters even without any fine-tuning. This is why few-shot learning works: the pre-trained model has already learned meaningful representations that transfer to new tasks.

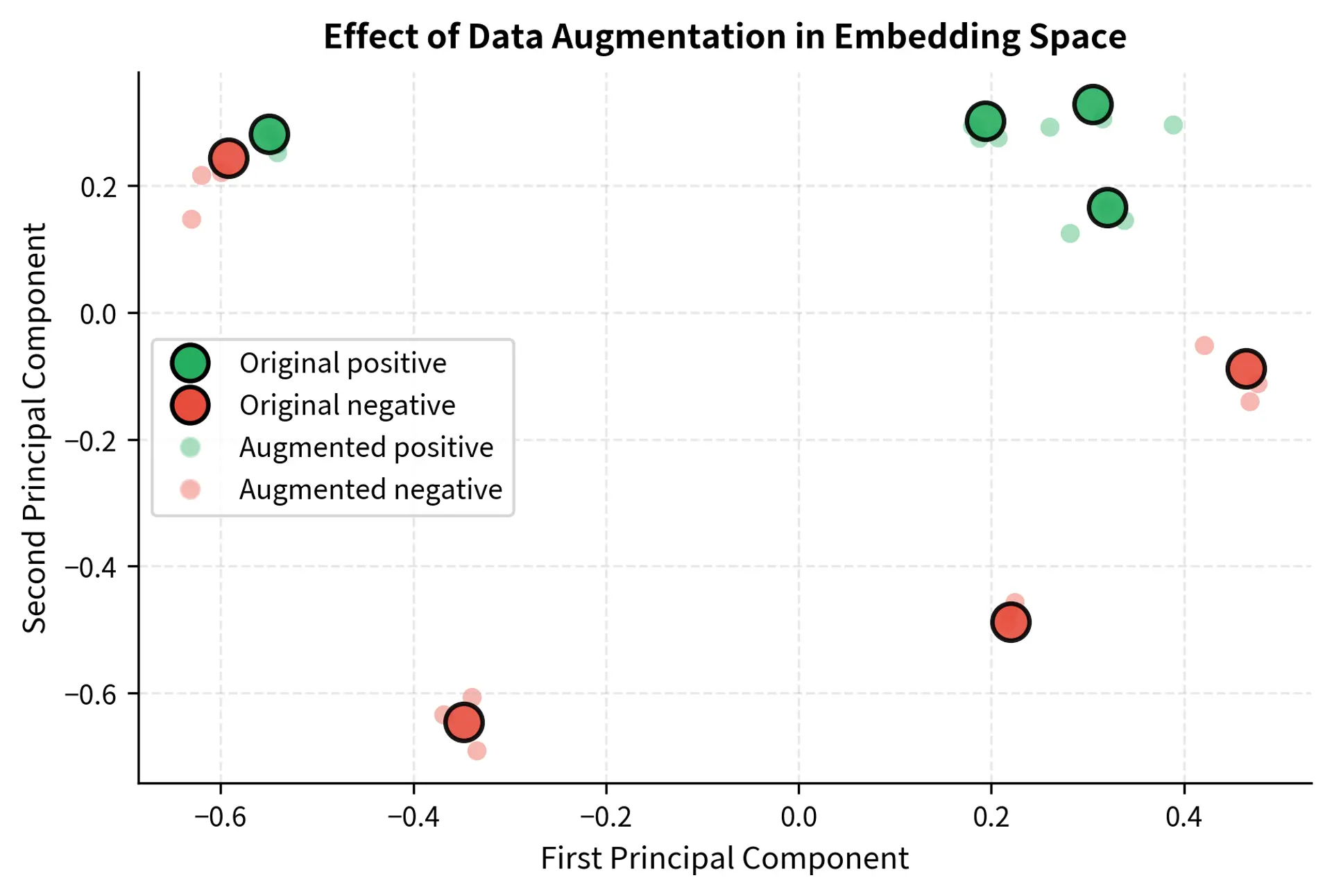

Now let's visualize how data augmentation affects the embedding space by comparing original and augmented embeddings.

Analyzing Sample Efficiency

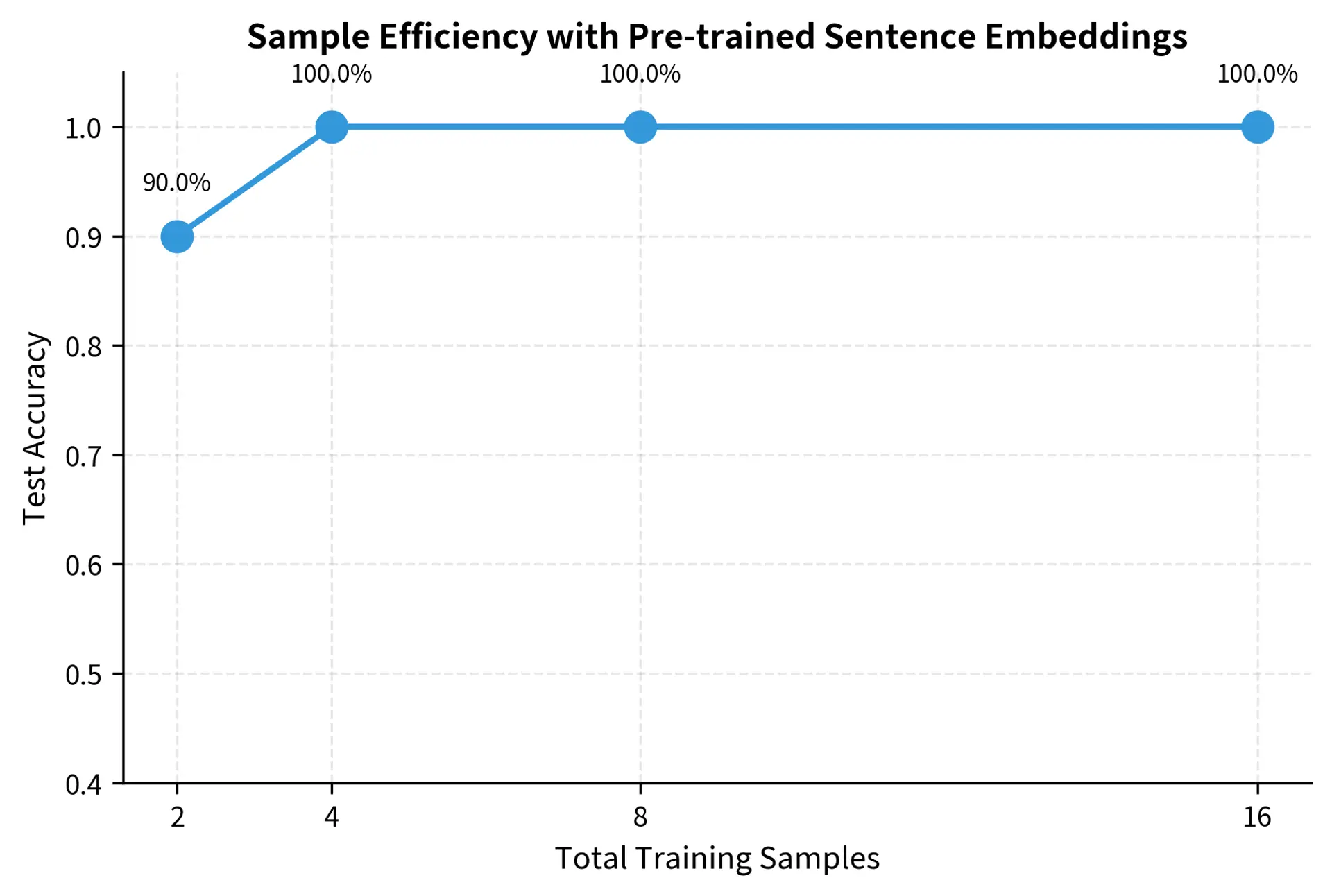

Let's examine how performance scales with training data size.

The sample efficiency curve reveals several important patterns. First, the steepest improvements come from the first few examples. Going from 1 to 2 examples per class often provides a larger accuracy gain than going from 4 to 8. Second, variance decreases with more samples. Few-shot learning with just 1-2 examples shows high run-to-run variance, making results less reliable. Third, pre-trained models make the curve much steeper than randomly initialized models would show. The model already understands language; it just needs a few examples to calibrate for the specific task.

Key Parameters

The key parameters used in these data efficiency techniques are:

- alpha_sr / alpha_ri / alpha_rs: Percentage of words to change for synonym replacement, random insertion, and random swap.

- p_rd: Probability of deleting a word in random deletion.

- margin: Distance threshold in contrastive loss. Negative pairs are pushed apart until their distance exceeds this margin.

- max_iter: Maximum iterations for the Logistic Regression solver.

Small Data Strategies

When working with limited data, several strategies maximize your chances of success.

Leverage Pre-training Alignment

Choose pre-trained models whose training data aligns with your target domain. A model pre-trained on scientific papers will be more sample-efficient for scientific text classification than a model trained on web text. This domain alignment provides stronger priors for the specific vocabulary and style of your target task.

Use Task Reformulation

When possible, reformulate your task to better match the pre-training objective. Classification as fill-in-the-blank (PET), question answering as span extraction, and other reformulations can dramatically improve few-shot performance by leveraging what the model already knows how to do.

Apply Regularization Aggressively

With limited data, overfitting is the primary enemy. Apply strong regularization: high dropout, weight decay, early stopping based on validation loss (even with few validation examples), and data augmentation. It's better to underfit slightly than to memorize the few training examples.

Ensemble Over Random Seeds

Train multiple models with different random seeds and combine their predictions. This reduces variance and provides more stable results than any single model. With few-shot data, the specific random initialization and training order can significantly impact results.

Consider Label Efficiency vs. Computation

Sometimes it's better to use a larger pre-trained model with fewer labeled examples than a smaller model with more labels. The next part of this book covers parameter-efficient fine-tuning methods like LoRA that make it practical to adapt very large models with limited computational resources.

Limitations and Impact

Data augmentation and few-shot techniques have important limitations that practitioners must understand. Text augmentation, unlike image augmentation, can easily change meaning or introduce grammatical errors. Synonym replacement might substitute words with subtly different connotations ("slender" vs. "skinny"), and random operations can create awkward or nonsensical sentences. The quality of augmented data is often lower than real data, meaning there are diminishing returns to aggressive augmentation.

Few-shot fine-tuning also exhibits concerning instabilities. Results can vary dramatically based on which specific examples are selected for training, the random seed used for initialization, and the order in which examples are presented. A model that appears excellent on one run might perform poorly on another. This variance is especially problematic when the "best" model is selected based on a small validation set, as the selection itself may just be fitting to noise.

Domain shift presents another challenge. Few-shot techniques work best when the target task is similar to what the model encountered during pre-training. For highly specialized domains with unique vocabulary, unusual document structures, or technical content unlike anything in the pre-training data, more labeled examples may be necessary regardless of the techniques applied.

Despite these limitations, data efficiency techniques have transformed what's practically achievable with NLP. Tasks that once required months of annotation can now be tackled with days of labeling. This democratization allows smaller organizations, practitioners with limited budgets, and applications in data-scarce domains to benefit from state-of-the-art language AI. The combination of large pre-trained models with smart adaptation strategies has fundamentally shifted the trade-offs in building NLP systems.

Summary

This chapter explored techniques for maximizing the value of limited labeled data in fine-tuning.

The sample efficiency spectrum ranges from zero-shot inference through few-shot fine-tuning to large-scale adaptation. Pre-trained models fundamentally change the relationship between data quantity and model performance, enabling strong results with far fewer examples than traditional approaches require.

Few-shot fine-tuning methods like Pattern-Exploiting Training (PET) reformulate tasks to match pre-training objectives, while SetFit uses contrastive learning to amplify few-shot data through pair generation. These techniques can achieve strong performance with just 8-32 labeled examples per class.

Data augmentation techniques for text include synonym replacement, back-translation, random operations (deletion, swap, insertion), embedding-space mixup, and contextual augmentation using language models. While less straightforward than image augmentation, these methods can meaningfully expand small datasets.

Sample efficiency patterns emerge from pre-training, which provides strong linguistic priors that reduce the need for task-specific data. Features learned from massive unlabeled corpora transfer effectively to downstream tasks with minimal adaptation.

Small data strategies emphasize domain-aligned model selection, task reformulation, aggressive regularization, ensembling across random seeds, and considering the trade-off between label efficiency and model size.

The next part explores parameter-efficient fine-tuning methods like LoRA, which extend these efficiency principles to model adaptation itself, allowing large models to be customized with minimal computational cost and memory overhead.

Quiz

Ready to test your understanding? Take this quick quiz to reinforce what you've learned about fine-tuning data efficiency and few-shot learning techniques.

Comments