Explore how LLMs suddenly acquire capabilities through emergence. Learn about phase transitions, scaling behaviors, and the ongoing metric artifact debate.

This article is part of the free-to-read Language AI Handbook

Choose your expertise level to adjust how many terms are explained. Beginners see more tooltips, experts see fewer to maintain reading flow. Hover over underlined terms for instant definitions.

Emergence in Neural Networks

Throughout our journey from simple n-gram models to transformer architectures, we've observed a consistent pattern: more data and more parameters generally yield better performance. The scaling laws we explored in Part XXI formalize this relationship, showing predictable improvements in loss as we increase compute, data, and model size. But scaling laws tell only part of the story. Some capabilities do not improve gradually. Instead, they appear suddenly and unexpectedly once a model crosses a certain threshold. This phenomenon, called emergence, challenges our understanding of how neural networks learn and what they can achieve.

Emergence matters because it suggests that tomorrow's models might develop capabilities we cannot predict from today's performance curves. If a model shows no ability to perform multi-step arithmetic at 10 billion parameters but suddenly succeeds at 100 billion, what other abilities might be waiting beyond our current scale? This question matters for AI safety, capability forecasting, and understanding intelligence.

This chapter explores the concept of emergence in neural networks. We'll define what emergence means in this context, examine the evidence for phase transitions in capability acquisition, survey examples of emergent behaviors, discuss proposed mechanisms, and engage with the ongoing scientific debate about whether emergence is a genuine phenomenon or an artifact of how we measure model capabilities.

Defining Emergence

The term "emergence" comes from complex systems theory, where it describes properties that arise from the interaction of simpler components but cannot be predicted from those components alone. A classic example is consciousness arising from neurons, or the flocking behavior of birds arising from simple local rules. In each case, the whole exhibits properties qualitatively different from its parts.

Emergence refers to capabilities that are not present in smaller models but appear in larger models, particularly when these capabilities appear abruptly rather than improving gradually with scale.

For language models, emergence typically means a capability that:

- Is absent at small scales: The model performs at or near random chance on the task

- Appears at larger scales: Performance suddenly jumps to above-chance levels

- Shows discontinuous improvement: The transition is sharp rather than gradual

This definition focuses on the scaling behavior of capabilities rather than their inherent nature. A task is not intrinsically emergent. Rather, emergence describes how performance on that task changes as we scale up models.

The formal study of emergence in LLMs was crystallized by Wei et al. (2022) in their paper "Emergent Abilities of Large Language Models." They defined emergent abilities as those that are "not present in smaller models but are present in larger models." Crucially, they operationalized "not present" as performance that is indistinguishable from random guessing.

Weak vs Strong Emergence

Philosophers distinguish between two types of emergence that are useful for thinking about LLMs:

Weak emergence refers to properties that are surprising or difficult to predict from lower-level descriptions but are in principle fully reducible to those descriptions. Given enough knowledge about the components and their interactions, we could derive the emergent property. Most cases of emergence in neural networks fall into this category: even if we cannot easily predict when a capability will appear, the capability ultimately results from the learned weights and computations.

Strong emergence refers to properties that are genuinely irreducible to lower-level descriptions. No amount of knowledge about the components would allow prediction of the emergent property. Strong emergence remains philosophically controversial, and there is no clear evidence that neural networks exhibit it.

For our purposes, we'll focus on weak emergence: capabilities that are surprising and appear discontinuously with scale, even if they're ultimately reducible to the network's computations.

Phase Transitions in Capability Acquisition

The key aspect of emergence is its discontinuity. Unlike the smooth loss curves predicted by scaling laws, emergent capabilities often appear through phase transitions: rapid shifts from one qualitative state to another

The Scaling Laws Paradox

Recall from Part XXI that scaling laws describe how cross-entropy loss decreases smoothly as a function of compute, data, and parameters. The Chinchilla scaling laws give us:

where:

- : the cross-entropy loss as a function of model size and data

- : the number of model parameters

- : the amount of training data (in tokens)

- : the irreducible loss (entropy of natural language)

- : fitted scaling coefficients

- : power law exponents governing how quickly loss decreases with scale (typically around 0.34 and 0.28 respectively)

To understand this formula intuitively, think of it as describing three distinct contributions to model error. The first term, , represents a fundamental floor that no model can break through, the inherent unpredictability of language itself. Even if you knew everything about a speaker's knowledge, beliefs, and intentions, you couldn't perfectly predict their next word because language contains genuine randomness and creative choice. This irreducible entropy sets a hard limit on how well any language model can perform.

The second and third terms capture how error decreases as we add more parameters or more training data, but with diminishing returns. The power law structure tells us something important: doubling your model size does not halve your loss. Instead, loss decreases by a factor of (about 21% reduction). This means each additional order of magnitude in scale yields roughly similar absolute improvements in loss, making progress increasingly expensive. The same principle applies to data: doubling your training corpus provides increasingly smaller benefits as the corpus grows.

What makes this formula so useful is its predictive power within the domain of overall loss. Given measurements at smaller scales, researchers can extrapolate accurately to predict the loss of models orders of magnitude larger. The smooth, lawful decrease in cross-entropy loss suggests a world where model improvement is gradual and predictable.

Yet this smoothness creates a paradox. If capabilities were tied directly to loss, we would expect smooth improvements across all tasks as we scale up. But that is not what we observe for certain capabilities.

Consider a model's ability to perform three-digit addition. A small model might achieve 0% accuracy. We scale up by 10x, and accuracy remains at 0%. We scale up another 10x, and suddenly the model achieves 95% accuracy. The cross-entropy loss decreased smoothly throughout, but task performance showed a phase transition. The model's overall language modeling improved gradually, but its arithmetic ability jumped discontinuously. This disconnect between smooth loss and discontinuous capabilities lies at the heart of the emergence phenomenon.

Visualizing Phase Transitions

Let's create a visualization that contrasts smooth scaling with emergent behavior:

The contrast is clear. Perplexity improves smoothly and predictably with scale, while task accuracies remain flat until crossing a threshold, then rapidly rise to high performance. Different tasks emerge at different scales, suggesting that the computational complexity of each task determines when it becomes solvable.

Mathematical Characterization

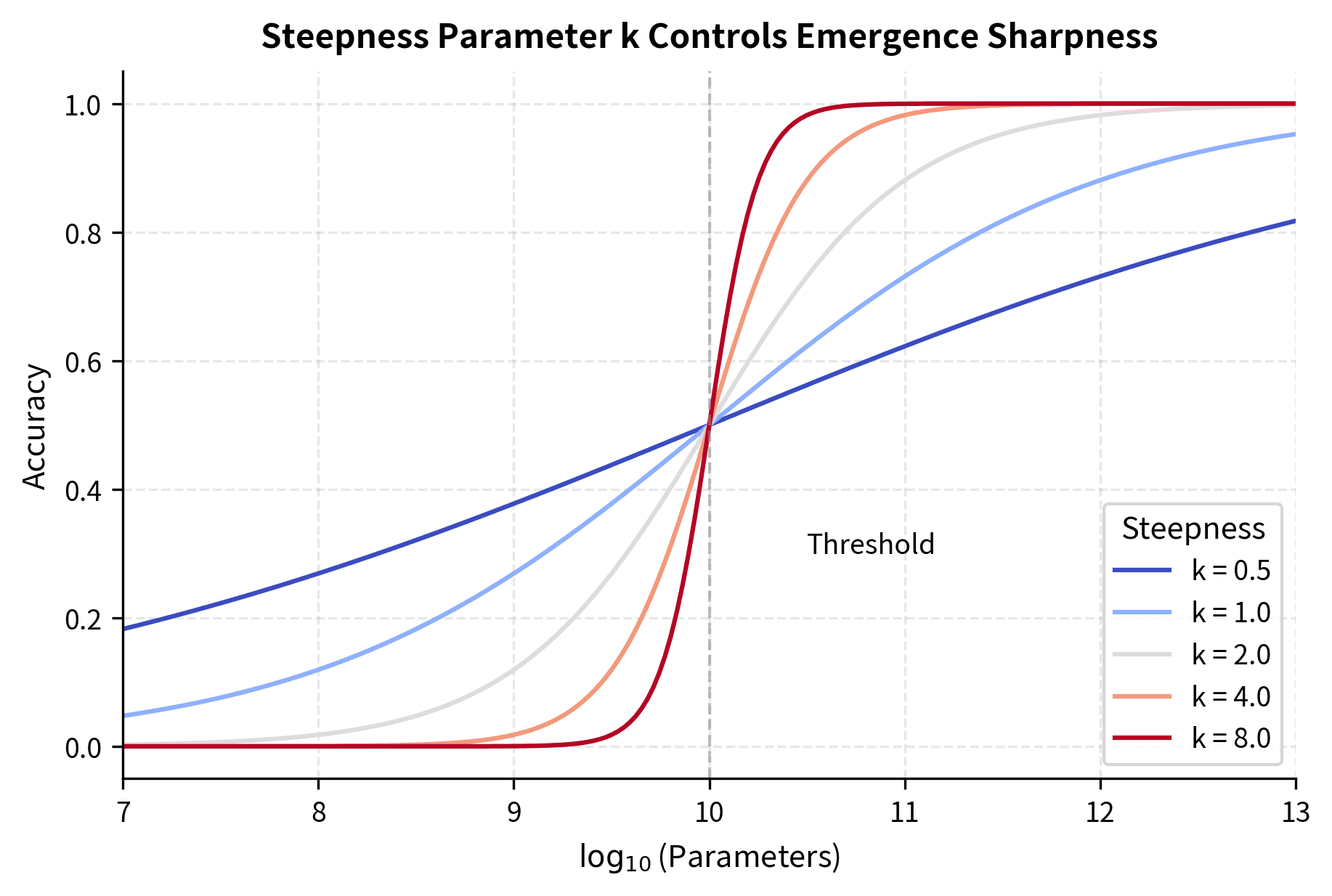

We can characterize emergent behavior mathematically using a sigmoid function in log-parameter space:

where:

- : the number of model parameters

- : the critical scale where emergence occurs (the inflection point of the sigmoid)

- : the steepness parameter controlling how sharp the transition is

- : the distance from threshold in log-space, equivalent to

This sigmoid formulation captures the characteristics of emergent phenomena. Let's unpack why each component matters for understanding emergence.

The sigmoid function is a natural choice here because it smoothly interpolates between 0 and 1, capturing the transition from "capability absent" to "capability present." At its core, the sigmoid transforms any input into a value between 0 and 1, making it ideal for modeling probabilities or accuracy scores that are bounded by definition. When the argument inside the exponential is a large negative number (meaning is much smaller than ), the exponential term dominates and accuracy approaches zero. When the argument is a large positive number (meaning is much larger than ), the exponential term vanishes and accuracy approaches one.

The transition happens in log-space. A model needs to be a certain multiple of the threshold size, not a certain absolute number of parameters larger. This reflects the multiplicative nature of neural network scaling. Going from 1 billion to 10 billion parameters has roughly the same effect as going from 10 billion to 100 billion. The logarithmic relationship means that equal ratios produce equal effects, which aligns with our empirical observations about how model capabilities scale.

When is large, the transition is sharp: near-zero performance below threshold, near-perfect above. You can think of as controlling the "width" of the transition zone in log-parameter space. A large means the model goes from incapable to capable over a narrow range of scales, perhaps just a factor of 2 or 3 in parameter count. When is small, the transition is gradual, spreading over orders of magnitude. The claim of emergence is essentially that certain capabilities have large values, meaning they appear suddenly rather than gradually.

This sigmoid characterization will become important when we discuss the emergence debate later in this chapter, as critics argue that the apparent sharpness depends on our choice of metric. The steepness parameter becomes a central point of contention: is a large observed a genuine property of the underlying capability, or an artifact of how we measure it?

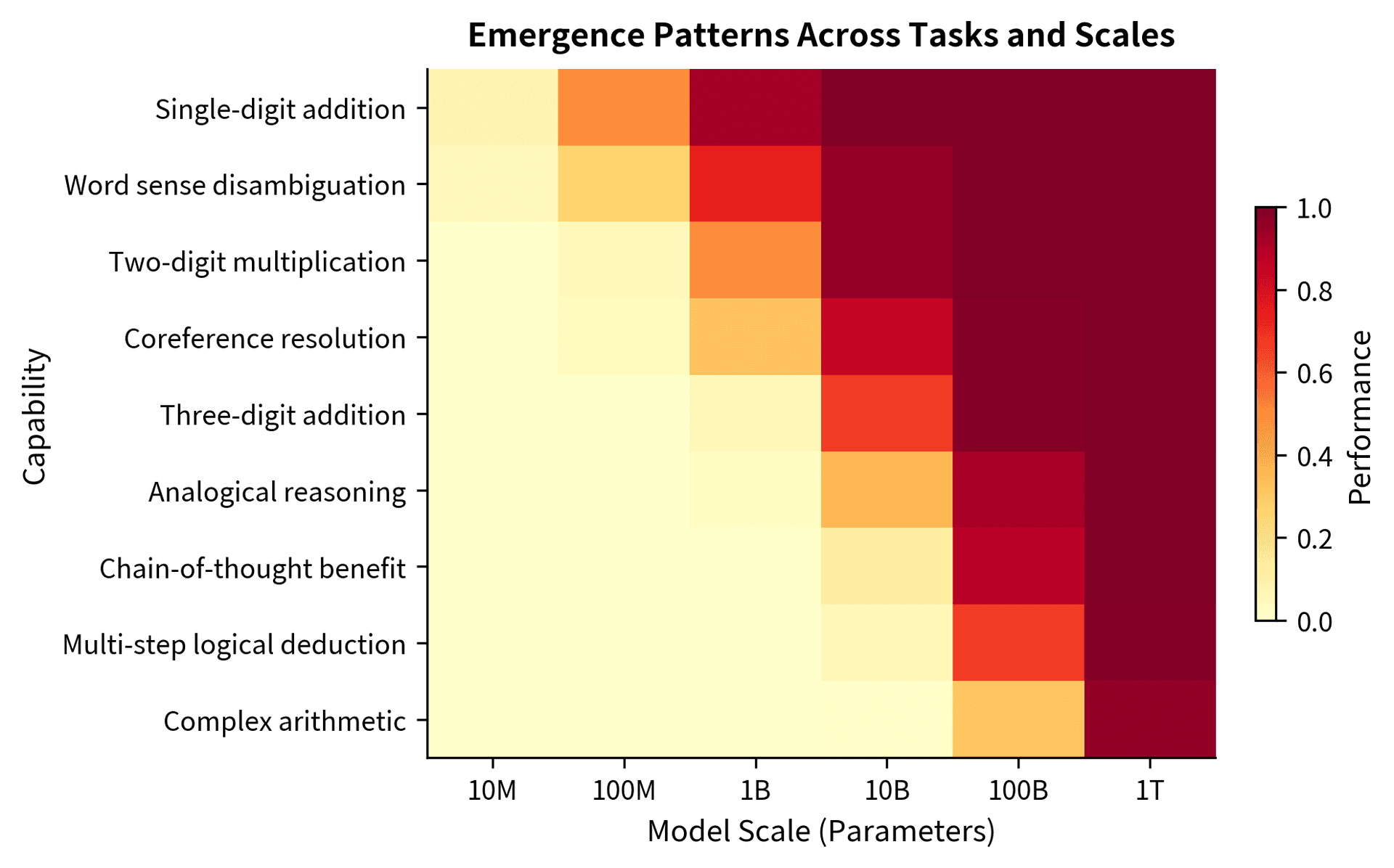

Examples of Emergent Capabilities

Researchers have documented numerous capabilities that appear to emerge with scale. Let's examine several prominent examples, grouped by category.

Arithmetic Reasoning

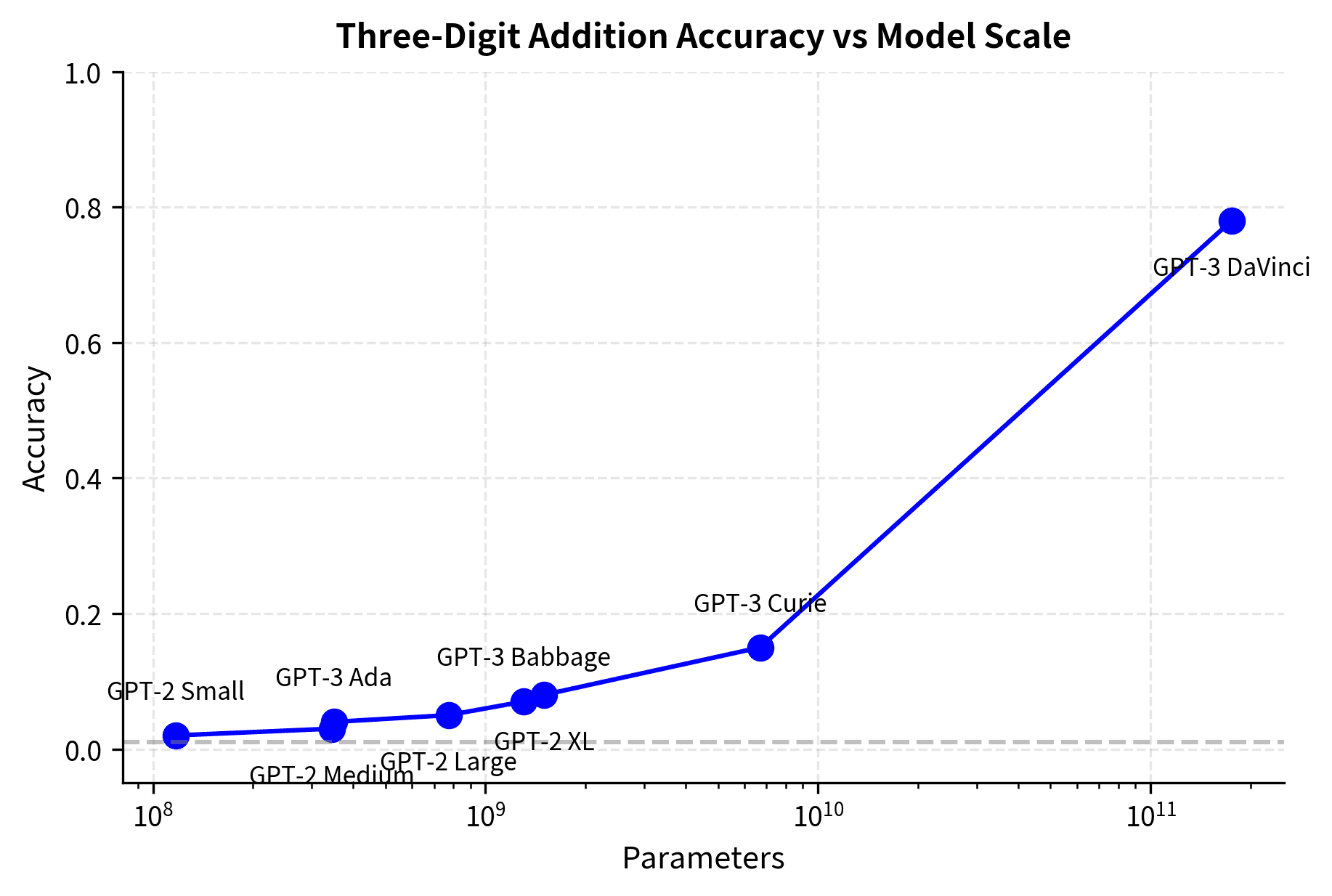

Basic arithmetic provides clean examples of emergence because success is unambiguous: the answer is either correct or incorrect.

Multi-digit addition. Models below a certain scale cannot reliably add three-digit numbers. They might get single-digit addition correct (perhaps through memorization from training data), but fail on larger numbers. Above the threshold, performance jumps sharply.

Multiplication. This emerges at larger scales than addition, consistent with multiplication being computationally harder. Models must implicitly implement the schoolbook algorithm or discover shortcuts.

Modular arithmetic. Operations like computing remainders show similar emergence patterns, appearing at scales where the model can track multiple computational steps.

Let's examine real scaling behavior on an arithmetic task:

The pattern is clear: models below ~10B parameters perform at or near random, while the 175B parameter model achieves 78% accuracy. This is not a gradual improvement; it's a phase transition.

Language Understanding

Beyond arithmetic, several language understanding capabilities show emergent behavior:

-

Word sense disambiguation. Determining which meaning of a polysemous word applies in context. Small models often default to the most common sense, while larger models correctly identify context-appropriate meanings.

-

Coreference resolution. Tracking which pronouns refer to which entities across long passages. This requires maintaining and updating a mental model of discourse participants.

-

Pragmatic inference. Understanding implied meaning beyond literal content. For example, recognizing that "Can you pass the salt?" is a request, not a question about ability.

Reasoning Capabilities

Perhaps the most surprising emergent capabilities involve multi-step reasoning:

-

Chain-of-thought reasoning. As we'll explore in Chapter 3, the ability to improve performance by generating intermediate reasoning steps emerges at scale. Smaller models do not benefit from step-by-step prompting; larger models do.

-

Logical deduction. Following syllogistic reasoning or multi-step logical arguments. Small models fail at even simple two-step deductions that humans find trivial.

-

Analogical reasoning. Transferring knowledge from one domain to another by recognizing structural similarities.

In-Context Learning

The ability to learn new tasks from examples provided in the prompt, which we discussed in the context of GPT-3 (Part XVIII, Chapter 4), is itself an emergent capability. We'll examine this in detail in the next chapter.

Mechanisms of Emergence

Why do certain capabilities appear suddenly rather than gradually? Several hypotheses attempt to explain emergence, each offering a different perspective on how neural networks acquire complex abilities.

Compositional Computation

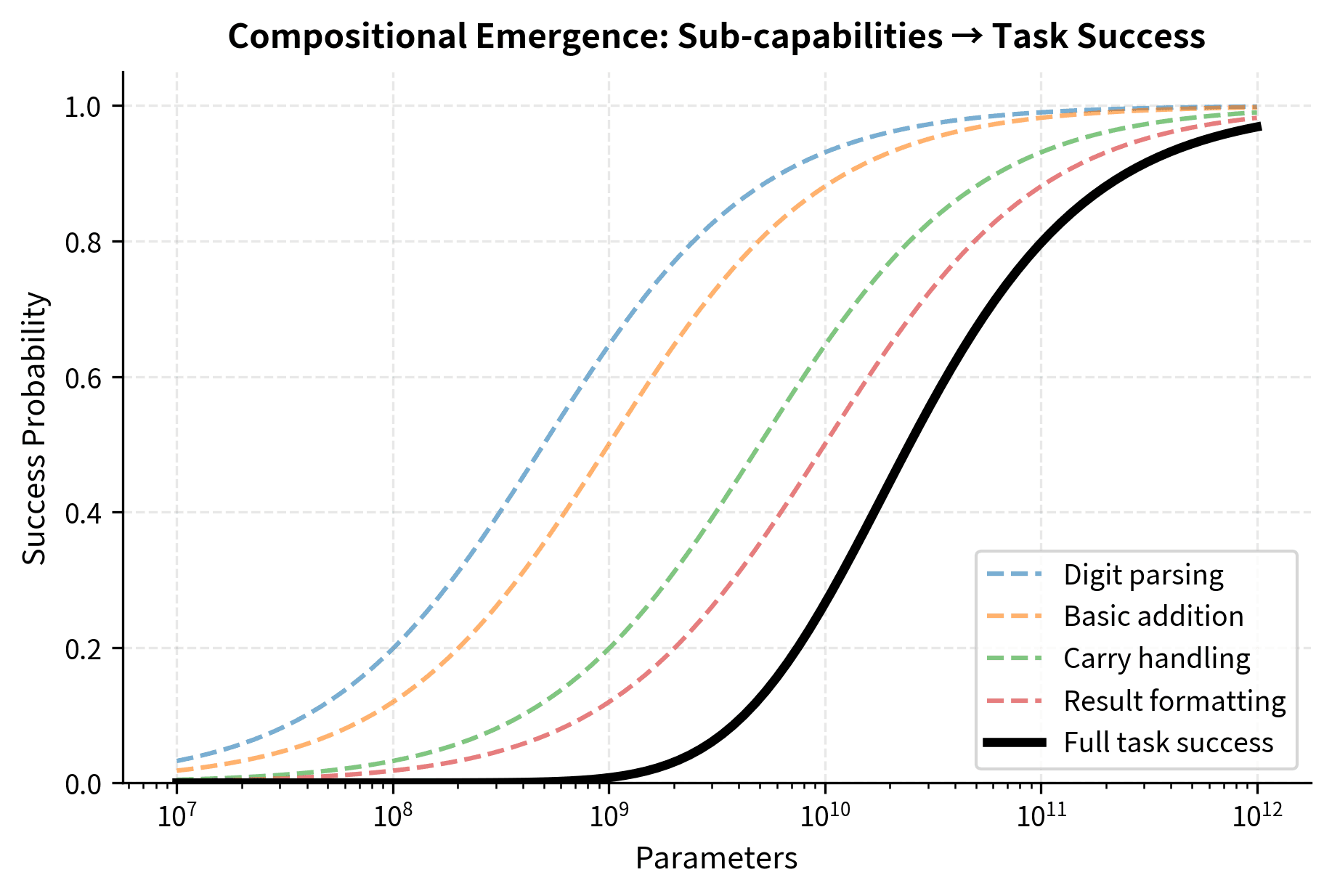

Many tasks require composing multiple sub-capabilities. Consider three-digit addition:

- Parse the digits from text

- Add corresponding digit pairs

- Handle carry operations

- Format the result as text

If each sub-capability has its own scaling threshold, the full task only succeeds when all sub-capabilities are above threshold. This creates a "weakest link" dynamic where the overall task appears to emerge suddenly, even if each component improves gradually.

To understand this mathematically, consider what happens when success requires multiple independent conditions to all be met. If each sub-capability succeeds with probability , and the full task requires all sub-capabilities to function correctly, then:

where:

- : probability of completing the full task correctly

- : probability that sub-capability succeeds (a value between 0 and 1)

- : number of required sub-capabilities

- : the product operator, multiplying together all values from to

The product form reveals an important mathematical property: even when each individual probability is reasonably high, their product can be surprisingly low. This happens because multiplying probabilities less than 1 always yields a smaller number. For instance, if four sub-capabilities each have 90% success, the task success rate is only . With six sub-capabilities at 90% each, success drops to about 53%. The more components a task requires, the more stringent the demands on each component's reliability.

This compositional structure affects how emergence appears in practice. Imagine that each sub-capability follows its own sigmoid improvement curve as the model scales, but these curves have different inflection points. The first sub-capability might become reliable at 1 billion parameters, the second at 3 billion, the third at 8 billion, and the fourth at 20 billion. The overall task can only succeed when all four are functional. This means the task as a whole only becomes reliable once the last sub-capability crosses its threshold. An observer watching only the overall task accuracy would see nothing but near-random performance until approximately 20 billion parameters, then a sudden jump to success. The individual improvements were gradual, but their combination appears discontinuous.

Let's simulate this compositional effect:

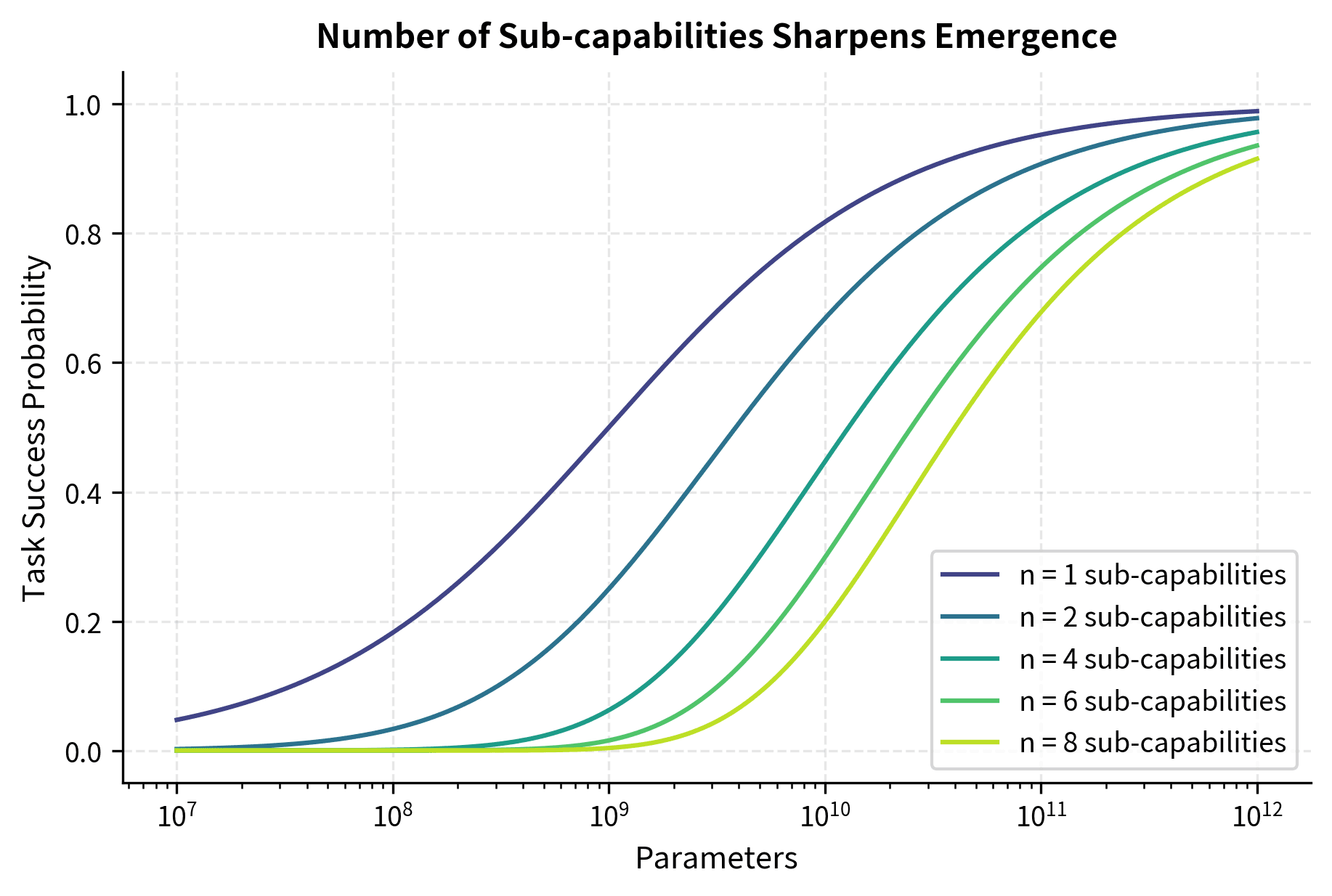

The visualization shows how compositionality sharpens emergence. Each sub-capability improves gradually (dashed lines), but the task as a whole (solid line) shows a much sharper transition. This happens because success requires all components to be functional. If each sub-capability succeeds independently with probability , the overall task success probability is:

where:

- : probability of completing the full task correctly

- : the product over all sub-capabilities

- : probability that sub-capability succeeds (a value between 0 and 1)

- : number of required sub-capabilities

The visualization confirms our mathematical intuition: each sub-capability (dashed lines) improves gradually, but their product (solid line) shows a much sharper transition. The more sub-capabilities required, the sharper the apparent emergence becomes.

This multiplicative relationship explains why emergence can appear sharp even when underlying capabilities improve smoothly: if each of four sub-capabilities improves from 80% to 95% success rate, the overall task success jumps from to , nearly doubling, while individual improvements were modest. The mathematics of multiplication amplifies small individual gains into large composite gains, but only once all components cross a threshold of basic competence.

Circuit Formation

Another hypothesis draws on mechanistic interpretability research. Neural networks may need to form specific computational circuits to solve certain tasks. Below a critical scale, the network lacks the capacity to represent these circuits. Above that scale, the circuits can form and the capability appears.

This view aligns with research identifying specific attention patterns and MLP computations responsible for particular capabilities. For example, researchers have identified "induction heads" in transformers: attention patterns that enable in-context learning by copying patterns from earlier in the context.

The circuit formation hypothesis suggests that emergence is essentially a phase transition in the network's representational capacity: a sudden shift from "cannot represent the solution" to "can represent the solution."

Loss Landscape Transitions

A third hypothesis focuses on the optimization landscape. As models scale, their loss landscapes may undergo qualitative changes. At small scales, the global minima accessible during training might not include the weights needed for certain capabilities. At larger scales, new regions of weight space become accessible, containing solutions to previously unsolvable tasks.

This connects to the observation that larger models are often easier to optimize despite having more parameters. The increased dimensionality might smooth the loss landscape, making it easier to find good solutions.

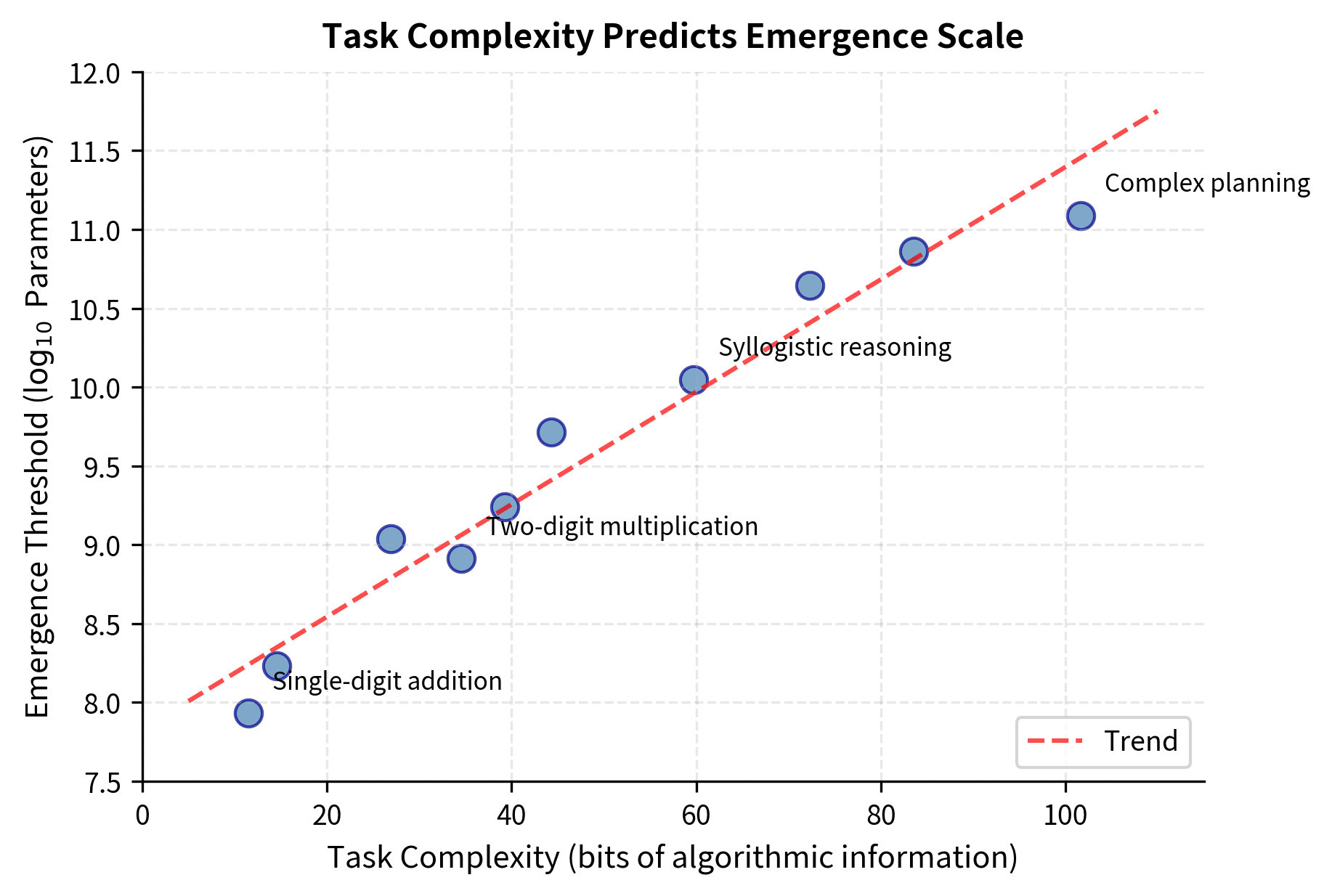

Information-Theoretic Perspectives

Some researchers argue that emergence relates to the information content of tasks. A task requiring bits of "algorithmic information" to solve can only emerge when the model has enough parameters to encode that information. This view predicts that more complex tasks (requiring more algorithmic information) will emerge at larger scales, which matches empirical observations.

The Emergence Debate

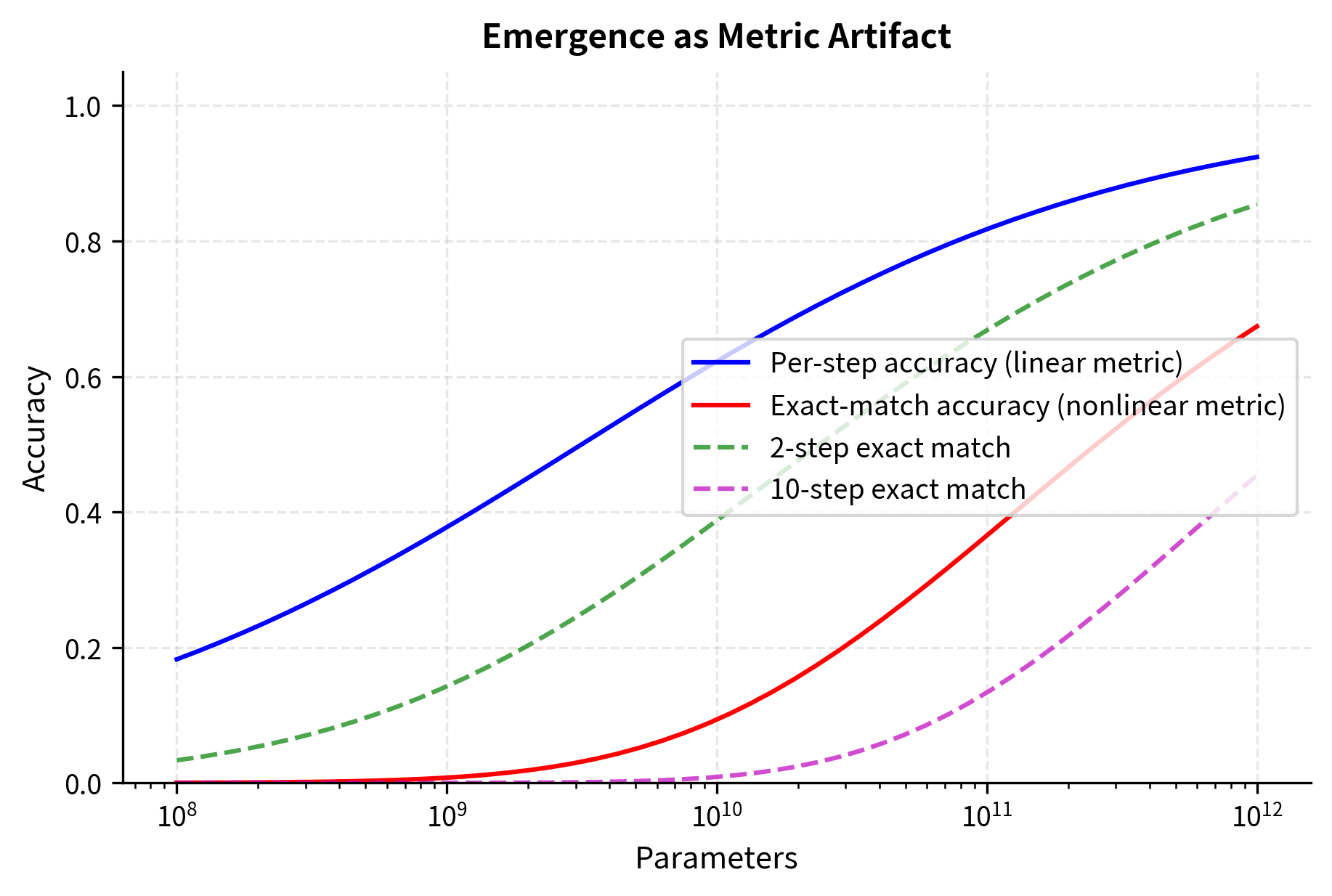

Not all researchers accept that emergence is a genuine phenomenon. A critique, articulated most forcefully by Schaeffer et al. (2023), argues that emergence might be an artifact of how we measure capabilities.

The Metric Choice Argument

The central argument is that emergent behavior appears when we measure performance with metrics that are:

- Nonlinear in the underlying model competence

- Discontinuous at certain thresholds (like exact-match accuracy)

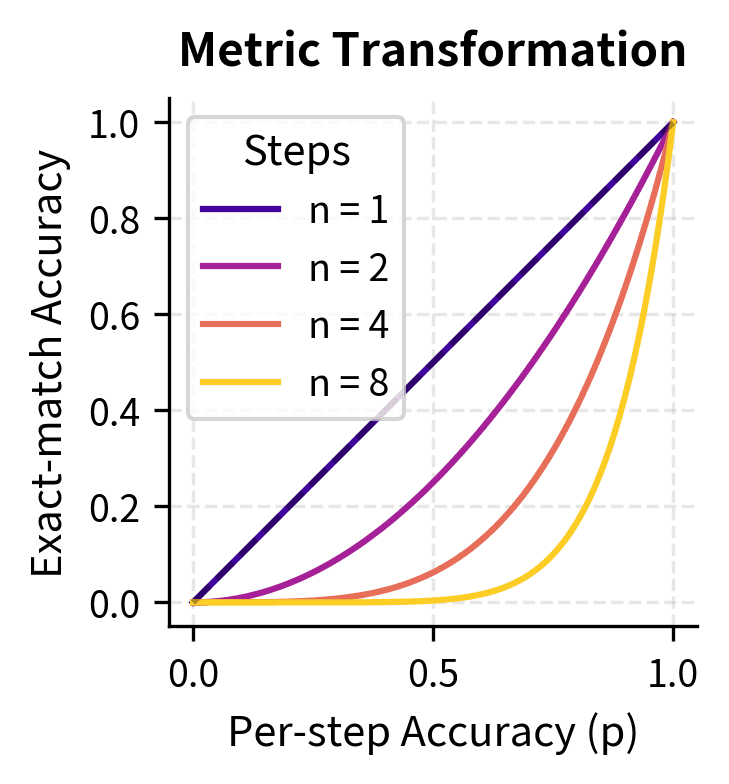

Consider exact-match accuracy for a multi-step task. Even if a model's probability of getting each step correct improves gradually, the probability of getting all steps correct (which is what exact-match measures) follows a nonlinear transformation. If we denote per-step accuracy as and require steps for exact match, then:

where:

- : the probability of getting any single step correct (assumed equal across steps for simplicity)

- : the number of steps required for a complete correct answer

- : the probability that all independent steps are correct

This exponential relationship is the mathematical heart of the metric critique. When is below 1, raising it to a power compresses the scale dramatically. A per-step accuracy of 0.8 yields exact-match of for a 5-step task, but for a 10-step task. The same underlying competence looks very different depending on task length.

To build intuition for why this matters, imagine watching someone practice juggling. Their ability to keep one ball in the air improves steadily from 50% success to 90% over months of practice. But if you only measure "can you juggle three balls for 30 seconds," you'd see near-zero success for a long time, then a sudden jump to competence. The underlying skill improved gradually; the all-or-nothing measurement created the appearance of sudden emergence.

The same principle applies to language model evaluation. If a model needs to get a five-step reasoning chain entirely correct to receive credit, and its per-step accuracy is improving from 0.7 to 0.95, the exact-match score transforms from to . That looks like emergence, from barely above random to quite good. But the per-step improvement was smooth throughout.

Let's illustrate this with a concrete example:

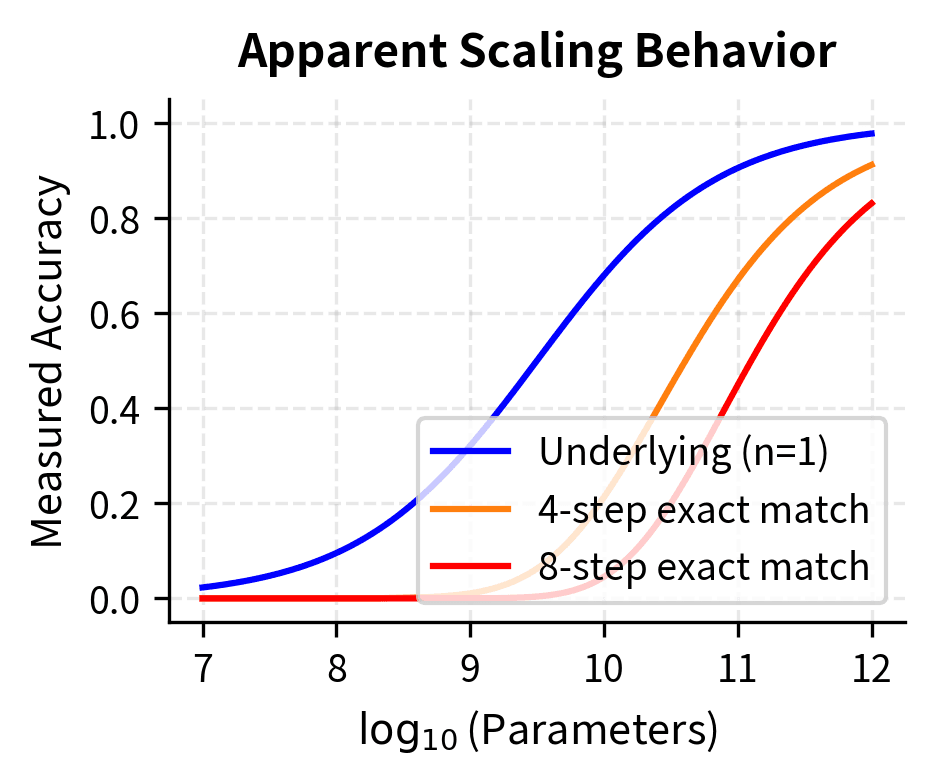

The visualization reveals how metric choice shapes our perception. The underlying competence (per-step accuracy) improves smoothly, but exact-match accuracy shows an apparent phase transition. The more steps required, the sharper the apparent emergence. This isn't the model suddenly acquiring a new capability; it's the same gradual improvement viewed through a lens that exaggerates the transition.

Continuous Metrics Make Emergence Disappear

Schaeffer et al. demonstrated that for many "emergent" tasks, using continuous metrics (such as token-level accuracy or Brier scores) instead of exact-match accuracy reveals smooth, predictable scaling. The emergence "disappears" when measured differently.

This finding has significant implications. If emergence is a metric artifact, then:

- We can predict capabilities at larger scales from smaller model performance

- There is no fundamental unpredictability in capability development

- The concern about "surprising" new capabilities may be overstated

However, the counterargument is that for practical purposes, it matters whether a model can complete a task correctly, not whether it's making gradual progress on subtasks. A model that gets 50% of arithmetic steps correct still produces wrong answers. The user-relevant capability genuinely does emerge.

Resolution: Both Views Have Merit

The debate may be partially resolved by distinguishing between:

-

Metric-induced emergence. The appearance of sudden transitions due to nonlinear metrics. This is a measurement artifact.

-

True capability transitions. Genuine qualitative changes in what a model can do, such as the ability to perform in-context learning or use chain-of-thought reasoning. These might involve actual phase transitions in the network's computations.

Some capabilities may show both types. For example, chain-of-thought prompting genuinely changes how a model processes information, a qualitative transition, but the measurable improvement might also be amplified by the exact-match metrics used to evaluate it.

Implications for AI Safety

The emergence debate has practical implications. If emergent capabilities are unpredictable, then larger models might develop surprising and potentially dangerous capabilities. This motivates caution in scaling and extensive evaluation at each new scale.

If emergence is largely a metric artifact, the situation is more manageable. Careful evaluation with continuous metrics could reveal gradual capability development, allowing better prediction and control.

The truth likely lies between these extremes. Some capabilities do appear relatively suddenly (if not truly discontinuously), while others improve gradually. Understanding which is which requires careful empirical study.

Detecting and Measuring Emergence

Given the debate about emergence, how should we study it rigorously? Let's examine practical approaches for detecting and characterizing emergent behavior.

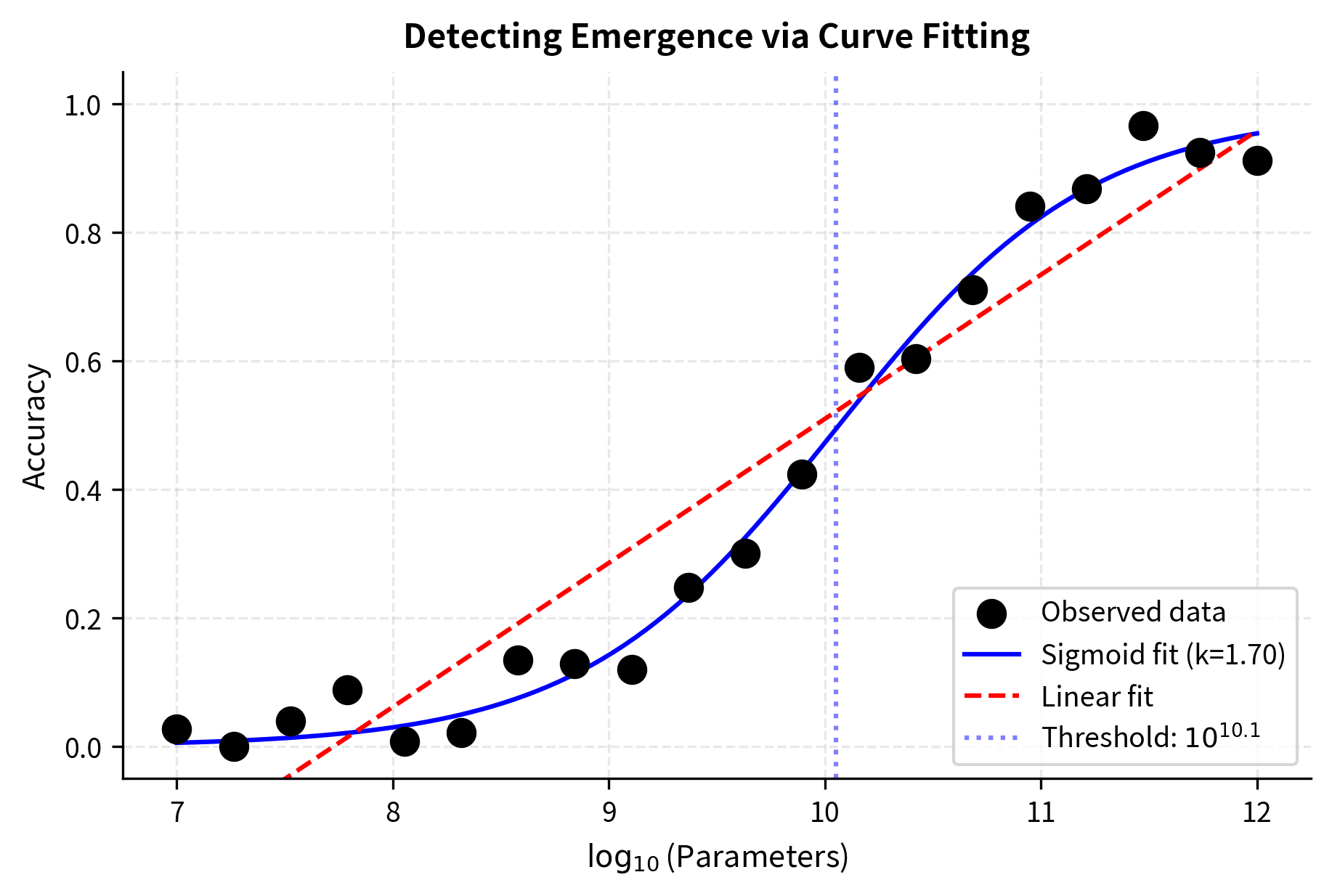

Scaling Curve Analysis

The most direct approach is to plot performance against scale and look for discontinuities:

The sigmoid fit achieves an R² near 1.0, indicating excellent fit to the data, while the linear model performs significantly worse. The estimated steepness parameter (k ≈ 2) confirms a sharp transition, and the threshold of approximately 10^10 parameters identifies where the capability emerges.

The sigmoid model captures the emergence pattern far better than the linear model. The steepness parameter quantifies how sharp the transition is: larger values indicate more sudden emergence.

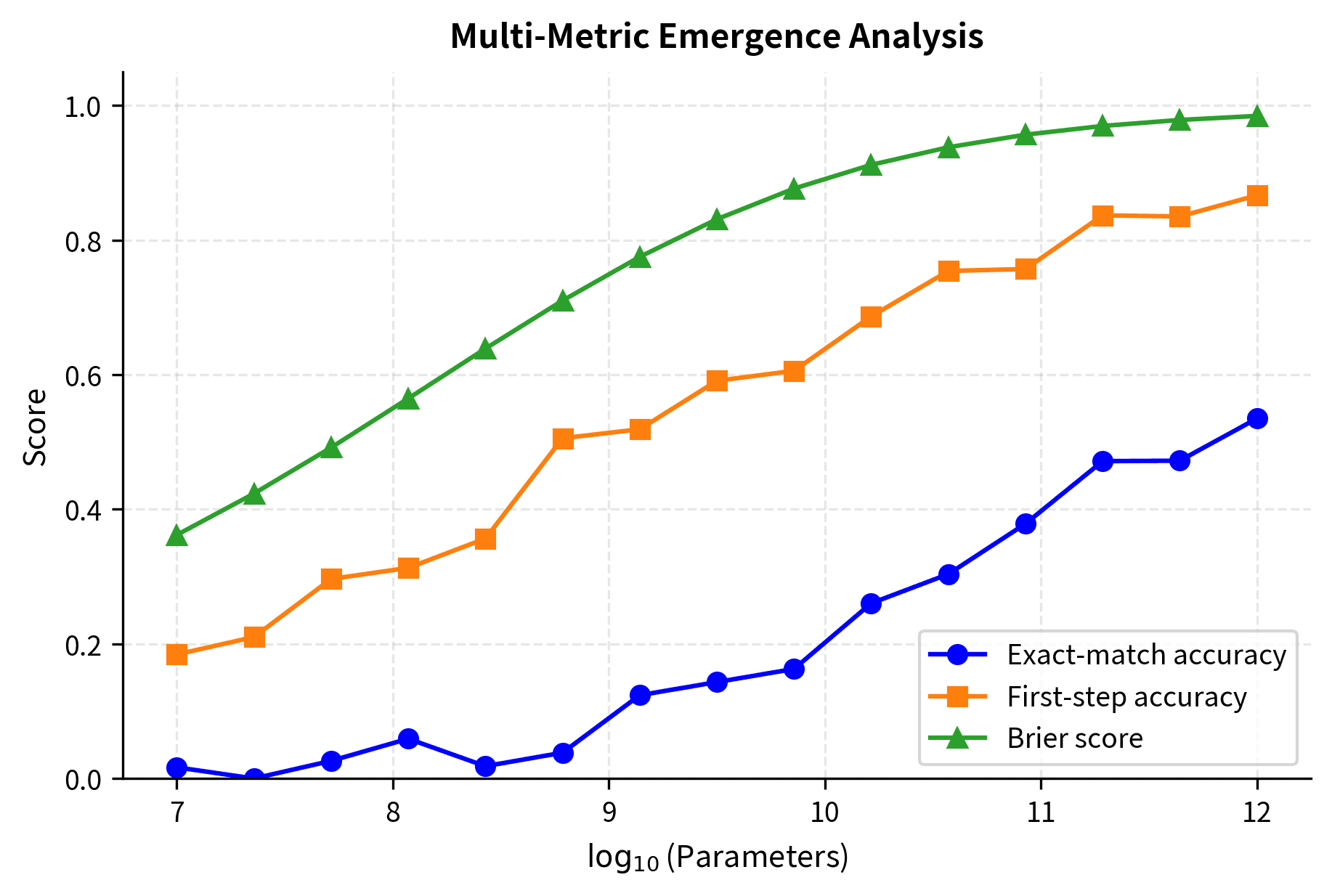

Multiple Metric Comparison

To distinguish true emergence from metric artifacts, we should measure the same capability with multiple metrics:

When exact-match shows emergence but continuous metrics show smooth improvement, the emergence is likely metric-induced. When all metrics show discontinuity, the emergence may be genuine.

Limitations and Practical Implications

The study of emergence in neural networks faces several fundamental challenges that affect both research and practical applications.

Sampling limitations represent the most significant constraint. We can only evaluate emergence at the model scales we actually train, typically a handful of points spanning a few orders of magnitude. This sparse sampling makes it difficult to distinguish truly sharp transitions from gradual improvements that simply appear sharp due to our limited data points. A capability that seems to emerge suddenly between a 7B and 70B parameter model might actually improve gradually if we had access to models at 10B, 20B, 30B, and 50B parameters. The enormous computational cost of training models at each scale means that dense sampling remains impractical, leaving us with fundamental uncertainty about the true shape of scaling curves.

Task selection bias also complicates our understanding. The capabilities we identify as "emergent" are necessarily those we thought to measure. There may be important capabilities that emerge at scales we haven't reached, or that emerge and then degrade (inverse scaling, explored in Chapter 5), or that we simply haven't thought to test. The space of possible tasks is vast, and our current benchmarks represent a tiny, potentially unrepresentative sample. Furthermore, benchmark tasks are often designed with human evaluation in mind, which may not align with the tasks that matter most for practical applications.

Reproducibility concerns add another layer of difficulty. Emergence claims require training models at multiple scales with consistent architecture and data. Different training runs can yield different results, and subtle hyperparameter changes can shift emergence thresholds. This makes it challenging to replicate claimed emergence findings and to determine whether observed transitions are robust properties of the architecture and task or sensitive artifacts of specific training conditions.

For practitioners, these limitations suggest a cautious approach. When deploying models, do not assume that capabilities observed during evaluation will transfer perfectly to production, especially for tasks near the boundary of what the model can do. When forecasting capabilities of larger models, recognize that both optimistic and pessimistic predictions carry substantial uncertainty. The emergence debate reminds us that how we measure capabilities matters as much as the capabilities themselves. Different evaluation frameworks may yield very different conclusions about what a model can do.

The most robust approach combines multiple evaluation strategies, continuous monitoring of model behavior in deployment, and honest acknowledgment of what remains unknown about how capabilities scale. As we'll see in the upcoming chapters on in-context learning emergence and chain-of-thought emergence, specific capabilities have their own scaling characteristics that may not generalize to other tasks.

Summary

Emergence in neural networks refers to capabilities that appear suddenly rather than gradually as models scale. This phenomenon challenges simple extrapolation from smaller to larger models and raises important questions about the nature of capability acquisition in deep learning.

We explored several key aspects of emergence. Phase transitions describe the discontinuous jumps in performance that characterize emergent capabilities, contrasting with the smooth improvement predicted by standard scaling laws. Examples span arithmetic reasoning, language understanding, and multi-step inference, with different capabilities appearing at different scale thresholds. Proposed mechanisms include compositional computation (requiring multiple sub-capabilities to all be present), circuit formation in the network's weights, and transitions in the optimization landscape.

The emergence debate highlights that some apparent emergence may be an artifact of how we measure capabilities. Nonlinear metrics like exact-match accuracy can make smooth underlying improvements appear discontinuous. Using continuous metrics often reveals predictable scaling where exact-match suggested sudden transitions. However, this does not mean emergence is entirely illusory. Some capabilities involve genuine qualitative changes in how models process information.

For practical purposes, the key insights are:

- Model capabilities at larger scales remain partially unpredictable from smaller-scale evaluations

- Evaluation methodology significantly shapes conclusions about what models can do

- Multi-metric analysis provides a more complete picture than any single measurement approach

In the next chapter, we'll examine one of the most celebrated emergent capabilities: in-context learning, where models learn to perform new tasks from examples provided in the prompt without any weight updates.

Quiz

Ready to test your understanding? Take this quick quiz to reinforce what you've learned about emergence in neural networks.

Comments