Learn how T5 reformulates all NLP tasks as text-to-text problems. Master task prefixes, classification, NER, and QA formatting for unified language models.

This article is part of the free-to-read Language AI Handbook

Choose your expertise level to adjust how many terms are explained. Beginners see more tooltips, experts see fewer to maintain reading flow. Hover over underlined terms for instant definitions.

T5 Task Formatting

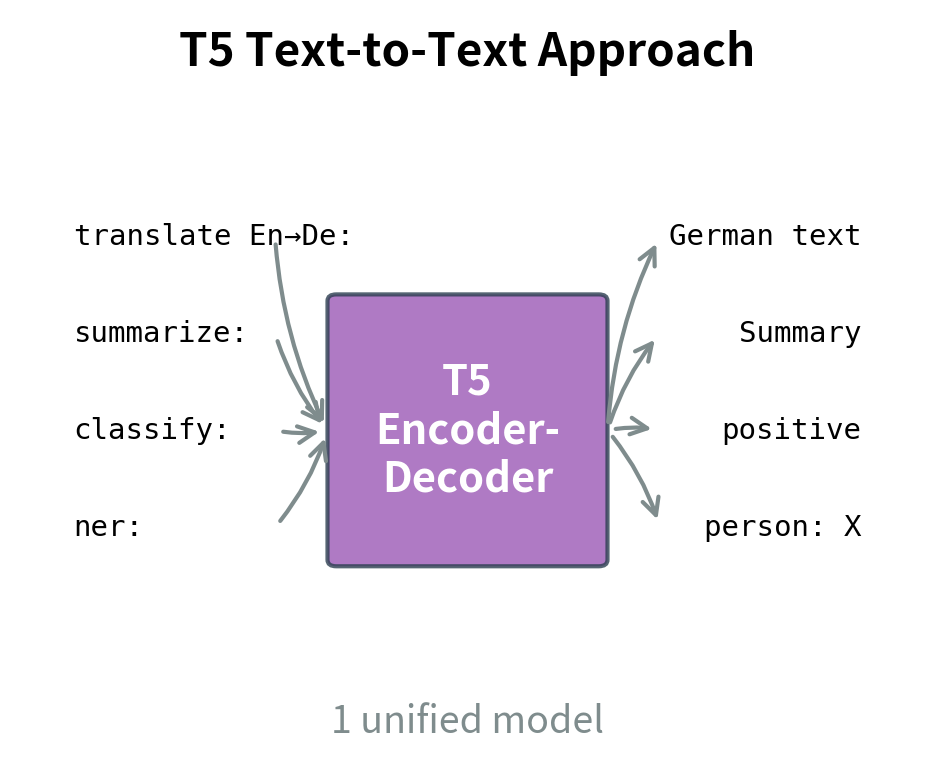

In the previous chapters, we explored T5's encoder-decoder architecture and its span corruption pre-training objective. But what makes T5 distinctive isn't just its architecture. The key insight is that every NLP task can be reformulated as a text-to-text problem. Classification, translation, summarization, question answering, and even structured prediction tasks like named entity recognition can all be expressed as "given this input text, produce this output text." This unification simplifies natural language processing by replacing many specialized methods with a single, coherent framework. This chapter explores how T5 achieves this unification through clever task formatting and what it means for building versatile language models.

The Text-to-Text Paradigm

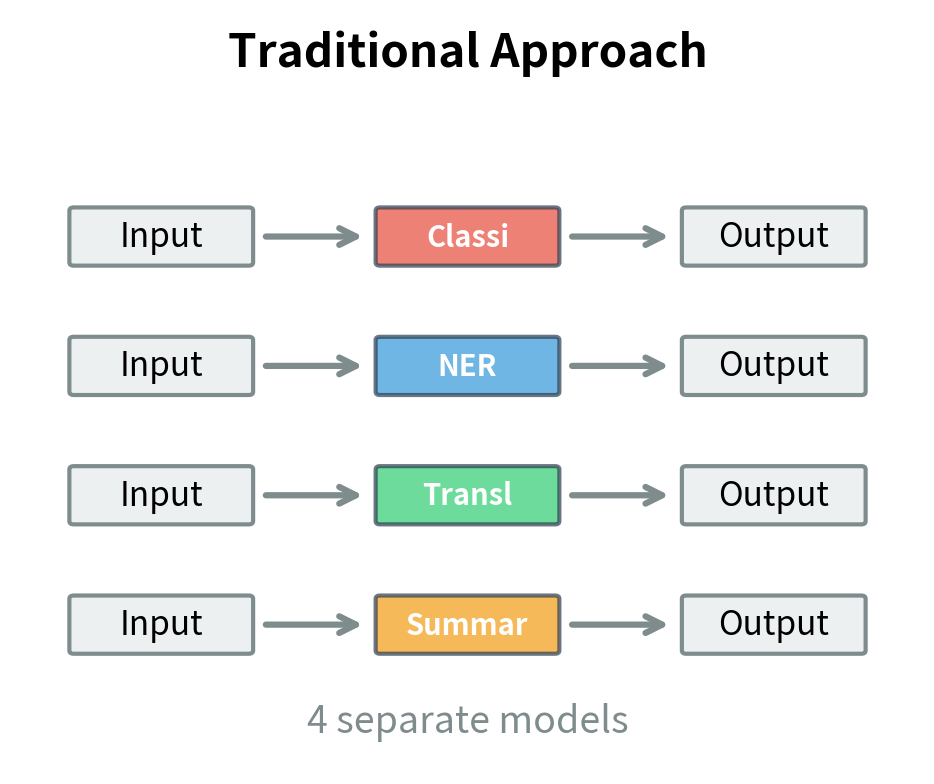

Traditional NLP systems treat different tasks as fundamentally different problems. A classifier predicts discrete labels. A tagger assigns one label per token. A generator produces sequences. Each task type requires its own output layer, loss function, and often its own model architecture. This fragmentation meant that advances in one area did not automatically transfer to others. A useful innovation in sequence labeling might require substantial rearchitecting to apply to classification tasks. T5 rejects this fragmentation entirely.

Text itself is a universal interface. Any output, whether a single label, a sequence of tags, or a complex annotation, can be serialized as a string. Consider what this means. A sentiment label like "positive" is just text. An entity tag sequence like "B-PER I-PER O B-LOC" is just text. A translated sentence is obviously text. If the output is a string, and the input is already a string, then every NLP task becomes sequence-to-sequence generation. This means a single model with a single architecture and training procedure can handle them all.

To see why this matters, consider the alternative. Before unified approaches like T5, a practitioner building a multi-task NLP system might need a BERT-based classifier for sentiment analysis with a classification head. They might need a separate BiLSTM-CRF for named entity recognition. They might also require a transformer encoder-decoder for translation and another architecture for summarization. Each model required its own training pipeline, its own hyperparameter tuning, and its own deployment infrastructure. The text-to-text paradigm collapses this complexity into a single model that learns to perform all tasks through the same mechanism.

The text-to-text paradigm treats every NLP task as translating from one text string to another. The model learns a unified mapping from input sequences to output sequences, regardless of whether the underlying task is classification, extraction, or generation.

This unification brings several benefits:

- Single architecture: The same encoder-decoder model handles all tasks without modification

- Shared pre-training: Knowledge learned during pre-training transfers to any downstream task

- Multitask learning: Multiple tasks can be mixed in a single training batch

- Zero-shot generalization: The model can attempt new tasks if given appropriate formatting

Beyond these practical benefits, this approach suggests that the boundary between "understanding" and "generation" may be more fluid than traditional NLP architectures imply. A model that can generate the correct answer to a question demonstrates understanding of both the question and the relevant context. A model that generates appropriate entity labels has learned to recognize those entities. Generation becomes the unified test of linguistic competence.

Task Prefixes

How does T5 know which task to perform when given an input? The answer is task prefixes, short text strings prepended to the input that signal the desired operation. This mechanism is remarkably simple yet surprisingly powerful, essentially teaching the model to follow instructions embedded in natural language.

Consider these examples:

"translate English to German: The house is wonderful.""summarize: The stock market fell sharply today after...""question: What is the capital of France? context: Paris is the capital..."

The prefix acts as a routing instruction, telling the model how to process the input and what output to generate. When the model sees "translate English to German:", it knows to treat the following text as English source material and produce German output. When it sees "summarize:", it understands that it should produce a condensed version of the following content. This is similar to how special tokens work in earlier chapters, but instead of learned embeddings with special meanings, T5 uses natural language instructions that the model learns to interpret through training.

This approach uses the model's core competency in understanding language to specify its behavior. Rather than introducing specialized tokens or architectural modifications for each task, T5 leverages the same linguistic representations it uses for everything else. The model learns that certain word patterns at the start of the input correlate with certain expected output patterns, much as it learns any other linguistic regularity.

The following examples show how task prefixes work in practice:

The model produces task-appropriate outputs based solely on the prefix: German translation for the first, French for the second, and a summary for the third. The prefix creates an implicit conditioning that shapes the entire generation process. Note that T5-small is a relatively small model, so translation quality may be limited compared to larger variants. The key insight is that the same architecture handles fundamentally different tasks through prefix-based routing.

Prefix Design Principles

The choice of prefix matters more than one might initially expect. T5's authors experimented with different prefix styles and found that clarity and consistency are more important than brevity. The prefix isn't just a tag. It's a specification that the model must parse and act upon. Ambiguous or inconsistent prefixes lead to ambiguous or inconsistent outputs. Effective prefixes share several characteristics:

- Explicit task naming: "translate", "summarize", "classify" clearly indicate the operation

- Parameter specification: "English to German" specifies source and target languages

- Consistent formatting: Using the same pattern ("task: input") across all tasks

- Natural language: Prefixes read as instructions a human would understand

Natural language prefixes work well. Because T5 is trained on vast amounts of natural text, it has strong priors about how language works. A prefix like "translate English to German:" leverages the model's understanding of what translation means, what English and German are, and how to interpret the colon as a delimiter. This is why natural language prefixes often work better than arbitrary codes or symbols. They use knowledge the model already has.

Here's how different prefix choices affect the same underlying task:

The comments highlight an important point. T5 was trained with specific prefixes like "cola sentence:", so using different formulations at inference time may produce unexpected results unless the model has been fine-tuned on the new format.

The specific prefixes used during training become part of the model's learned behavior. T5's original training used prefixes like "cola sentence:" for the CoLA grammaticality task, "sst2 sentence:" for sentiment analysis, and "translate English to German:" for translation. Using different prefixes at inference time may produce unexpected results unless the model has been fine-tuned on the new format. This highlights an important principle: the text-to-text paradigm is flexible but not magical. The model can only reliably perform tasks it has been trained to recognize through their prefixes.

Classification as Generation

Converting classification to generation might seem wasteful. Why generate text when you only need a label? This question highlights the efficiency versus flexibility trade-off that defines the text-to-text paradigm. But the benefits of unification outweigh the slight overhead, and the approach proves surprisingly powerful in practice.

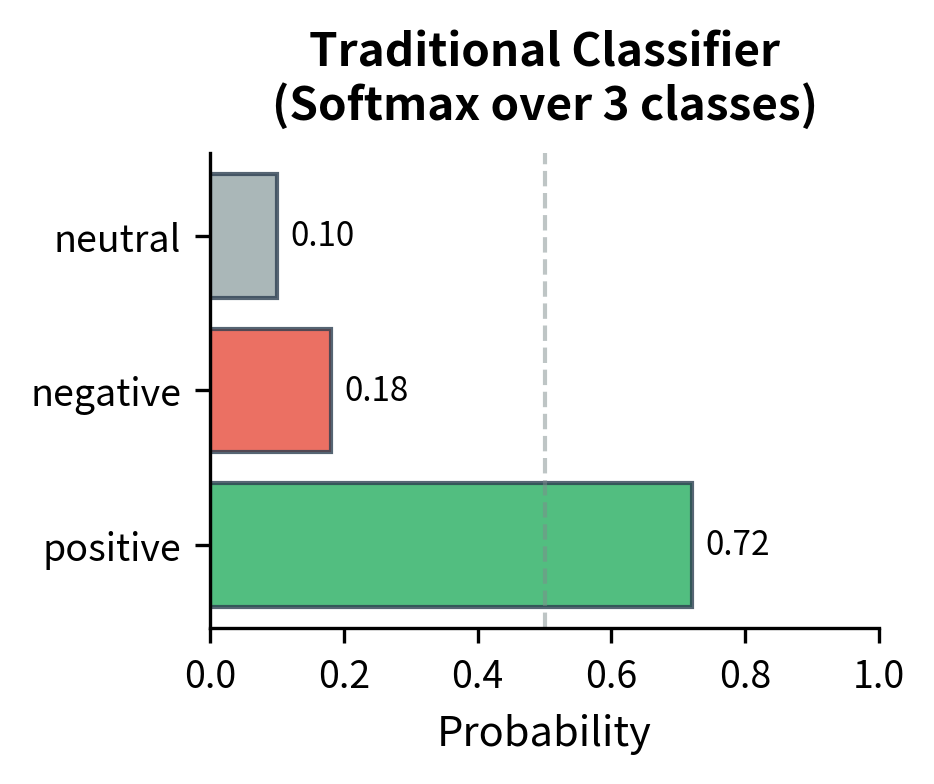

To understand why, consider what classification is. A classifier takes an input and selects one of several possible outputs. In traditional systems, this selection happens through a softmax over a fixed set of classes. In T5, the selection happens through generation. The "selection" is the model's choice of which label text to produce. The mechanism differs, but the underlying computation is conceptually similar. The model must encode the input, reason about its meaning, and produce an appropriate response.

For binary classification, the model simply generates a label token.

These examples show how sentiment classification maps to text generation. The model learns to produce "positive" or "negative" based on the input text. The third example with "?" as expected output illustrates an ambiguous case. Real training data would need a consistent strategy for handling mixed sentiment.

During training, the model learns to generate the appropriate label text. For SST-2 (Stanford Sentiment Treebank), T5 was trained to output "positive" or "negative". For CoLA (grammaticality), it outputs "acceptable" or "unacceptable". The choice of label text is arbitrary in principle. The model could learn to output "1" for positive and "0" for negative, but descriptive labels leverage the model's semantic understanding and tend to work better in practice.

Multi-class and Multi-label Classification

The text-to-text format naturally extends to more complex classification scenarios without requiring any architectural changes. This is where the paradigm's flexibility shines. A traditional multi-class classifier needs its output layer sized to the number of classes. Adding a new class means modifying the architecture. In T5, adding a new class just means introducing a new label string in the training data.

For multi-label classification, the model generates multiple labels separated by a delimiter. This approach is more flexible than traditional multi-hot encoding because the model can generate any number of labels and even labels it hasn't seen during training (though with uncertain accuracy). The model learns not just which labels to generate, but also the delimiter pattern and the approximate number of labels appropriate for different inputs.

Extracting Probabilities

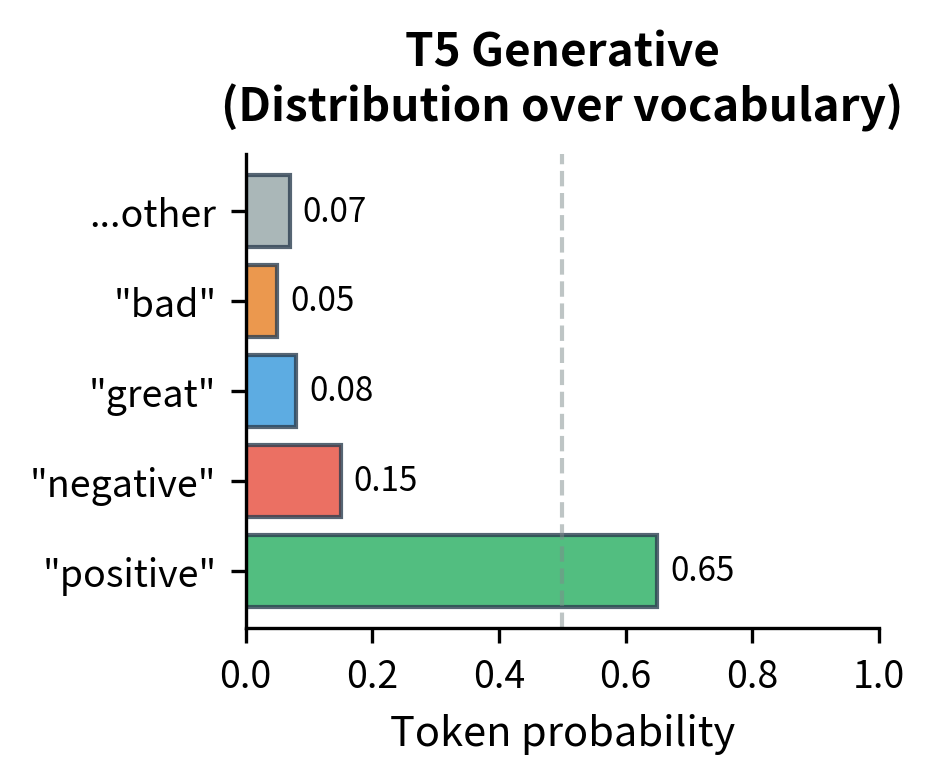

One apparent limitation of generation-based classification is losing access to prediction probabilities. Traditional classifiers output a probability distribution over labels. This is useful for calibration, thresholding, and uncertainty estimation. If a traditional classifier is 51% confident about "positive" and 49% about "negative", you know the prediction is uncertain. With greedy generation, you just get "positive" with no indication of the model's uncertainty.

T5 solves this by allowing access to the decoder's output logits. Since generation proceeds token by token, and each token is selected based on a probability distribution over the vocabulary, we can recover probability information by examining these distributions directly:

This approach scores how likely the model is to generate each candidate label given the input, recovering the probability information that traditional classifiers provide directly. The key insight is that we're not just looking at what the model generates, but at the probability distribution from which it generates. This distribution contains rich information about the model's confidence and the relative likelihood of alternative outputs.

Named Entity Recognition as Generation

Named entity recognition, as we covered in Part VI, traditionally uses BIO tagging to assign labels to each token. This approach is elegant for sequence labeling architectures that produce one output per input position. However, it doesn't naturally fit the text-to-text paradigm where input and output lengths can differ arbitrarily. Converting NER to text-to-text requires reformulating the task: instead of predicting per-token labels, the model generates the entities directly.

This reformulation changes what the model needs to learn. Instead of learning to classify each token independently, or with CRF dependencies, the model learns to read the input text, identify entity spans, and express those findings in a structured output format. This is closer to how humans perform entity recognition. We do not mentally label each word as B-PER or I-PER. We read the text and notice that "Marie Curie" is a person's name.

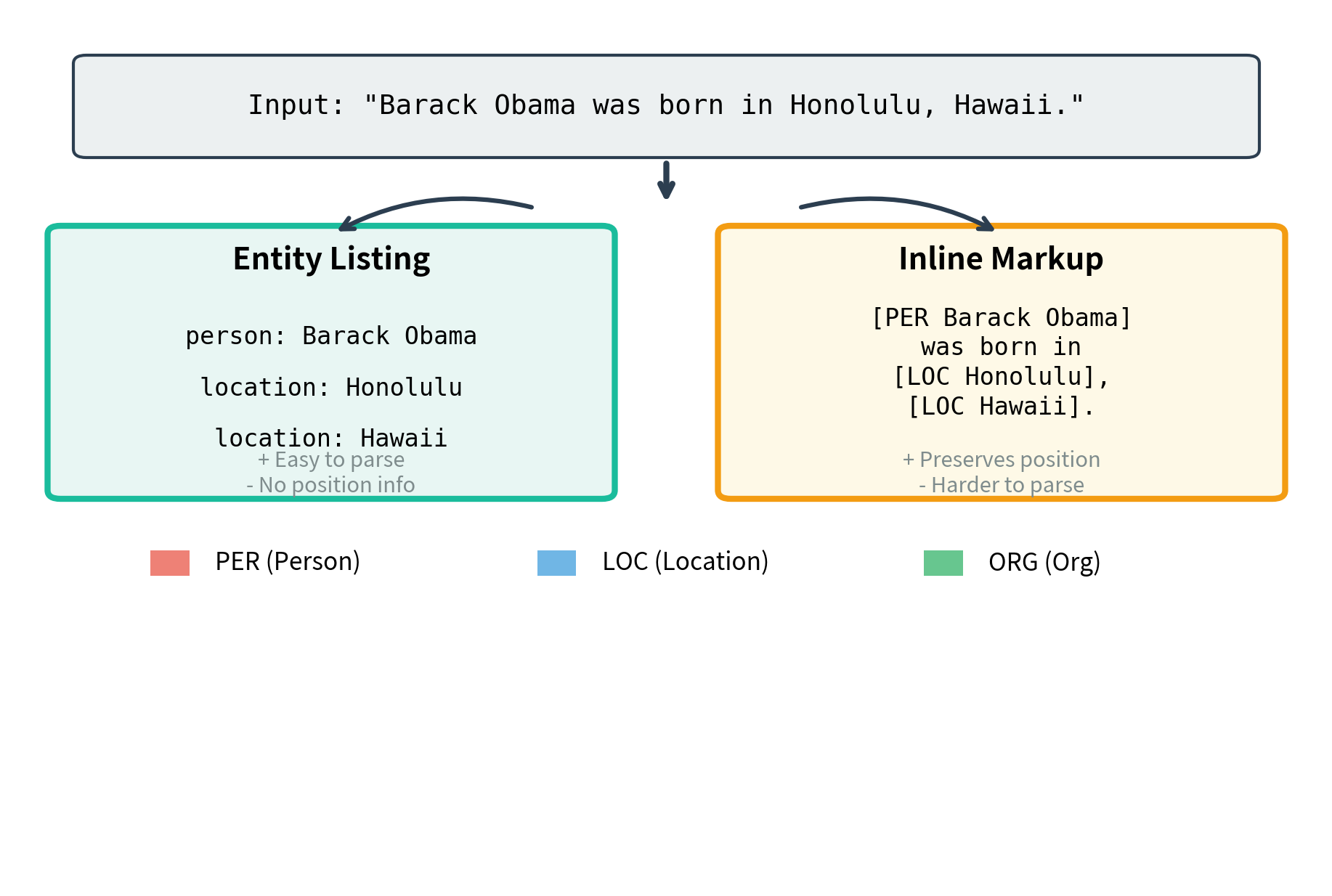

There are two main approaches to formatting NER as text generation:

Approach 1: Entity Listing

The model generates a structured list of entities and their types. This format separates the entity recognition task from positional information. It focuses purely on what entities exist and their types.

This format is intuitive and handles overlapping entities naturally, since each entity is listed separately regardless of position. The model learns a consistent pattern: type followed by colon, then entity text, with entities separated by commas. This regularity helps the model generalize to new entity types and new texts.

Approach 2: Inline Markup

Alternatively, entities can be marked inline with special delimiters. This approach preserves the original text structure while adding entity annotations.

This approach preserves entity positions and makes nested entities explicit, but requires careful parsing of the output. The inline format has the advantage of maintaining context around entities, which can help with certain downstream applications. However, it requires the model to regenerate the entire input with markup added. This is more computationally expensive and introduces more opportunities for the model to make mistakes.

Handling Edge Cases

The generative approach to NER introduces challenges that traditional sequence labeling doesn't face. Because the model generates entities as discrete items rather than labeling positions, it must handle various edge cases that don't arise in BIO tagging.

Training data must cover these edge cases consistently for the model to handle them reliably. The format chosen during training becomes critical. Mixing formats leads to inconsistent outputs. If some training examples list nested entities and others don't, the model won't learn a consistent policy for handling nesting. Practitioners must make deliberate choices about how to handle these edge cases and apply those choices uniformly across training data.

Question Answering as Generation

Question answering fits the text-to-text paradigm naturally, more so than most tasks. The core operation involves reading a question, consulting some source of knowledge, and producing an answer. This is inherently about transforming one text into another. Given a question and context, generate the answer:

The extractive example shows a simple fact lookup where the answer appears directly in the context. The multi-hop example requires combining information from multiple sentences, identifying that Apple makes the iPhone, then finding who founded Apple. This reasoning capability emerges from T5's pre-training on diverse text. The model learns not just to locate information, but to chain together facts and synthesize coherent answers.

T5 correctly extracts "Berlin" from the provided context. This demonstrates the open-book QA pattern where the model locates and returns the relevant information from the given passage rather than relying on memorized knowledge.

Open-book vs Closed-book QA

T5's text-to-text format supports a distinction that reveals what large language models actually learn. The format supports both open-book QA, where context is provided, and closed-book QA, where the model must rely entirely on knowledge encoded in its parameters.

Open-book QA provides the answer source explicitly. The model's job is comprehension and extraction: finding the relevant information in the provided text. Closed-book QA tests whether the model memorized relevant facts during pre-training. T5 demonstrated surprisingly strong closed-book QA performance, suggesting that large-scale pre-training encodes substantial world knowledge. This finding was influential in demonstrating that large language models do not just learn linguistic patterns. They also absorb and can retrieve factual information.

Abstractive vs Extractive Answers

Unlike span-based extractive QA models that can only copy text from the context, T5 can generate abstractive answers. This changes what question answering can accomplish. Traditional extractive models are limited to answers that appear verbatim in the source text. T5 can synthesize, paraphrase, and reason.

The synthesis example demonstrates this well. The word "two" doesn't appear anywhere in the context, yet it's the correct answer. The model must count the Nobel Prizes mentioned and express that count as a word. This kind of reasoning and synthesis goes beyond pattern matching. It requires comprehension and inference.

This flexibility is powerful but requires careful training data design. If training answers are always extractive, the model will learn to copy; if they are abstractive, it may introduce errors or hallucinations. The nature of the training data shapes the model's behavior in subtle but important ways.

Additional Task Formatting Examples

The text-to-text paradigm extends far beyond the examples we've covered. Its power is its universality. Essentially any NLP task that can be described as "given this text, produce that text" fits naturally into the framework. Let's examine formatting for several more task types:

Semantic Similarity

Sentence similarity tasks ask whether two sentences mean the same thing. This is a fundamental capability underlying many applications, from duplicate detection to paraphrase identification.

For graded similarity (STS-B benchmark), the output is a numerical score. This demonstrates how the text-to-text format handles continuous outputs by simply generating the number as text.

Natural Language Inference

NLI determines whether a hypothesis follows from a premise. This task tests logical reasoning and semantic understanding, asking the model to evaluate relationships between statements.

Text Correction

Grammar and spelling correction naturally fit the text-to-text format. The task is to transform erroneous text into corrected text.

Summarization with Length Control

T5 can be trained to follow length specifications. By incorporating length requirements into the prefix, the model learns to produce summaries of varying granularity.

Structured Data Generation

Even structured outputs can be serialized as text. This shows the text-to-text paradigm's flexibility. Any output that can be expressed as a string becomes a valid target.

These structured output examples hint at capabilities that would become central to later models. The ability to generate JSON, SQL, and code from natural language descriptions anticipates the code-generating and structured-reasoning capabilities of more recent large language models.

Building a Task Formatter

The following utility class handles task formatting consistently. This class encapsulates the formatting conventions we've discussed, providing a clean interface for preparing inputs across different task types.

Each formatted string follows a consistent pattern: a task-specific prefix followed by the input content. This consistency is key to T5's ability to route inputs to the appropriate behavior. The formatter class encapsulates these patterns, making it easy to ensure correct formatting across an application. By centralizing the formatting logic, we also make it easier to update formats if needed. Changing the formatter updates all usages automatically.

Parsing Generated Outputs

Generating text is only half the problem. For tasks with structured outputs, you need to parse the model's generations back into usable data. The model produces strings, but your application likely needs Python objects, database entries, or API responses. This parsing step bridges the gap between the model's text-based interface and the structured world of software systems.

The parsers successfully convert raw text outputs back into structured Python data. Classification outputs map to discrete labels, entity strings become lists of (type, text) tuples, and numeric scores parse to floats. Robust parsing is essential in production systems because model outputs may occasionally deviate from expected formats. A well-designed parser handles variations gracefully. It normalizes outputs where possible and fails gracefully when the output is truly unparseable.

Multitask Training

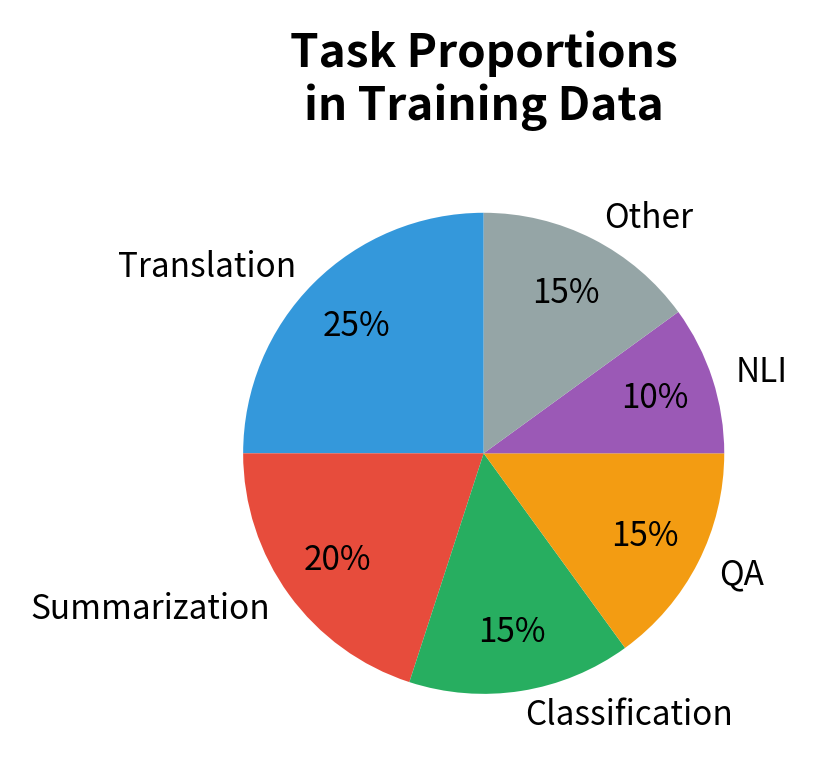

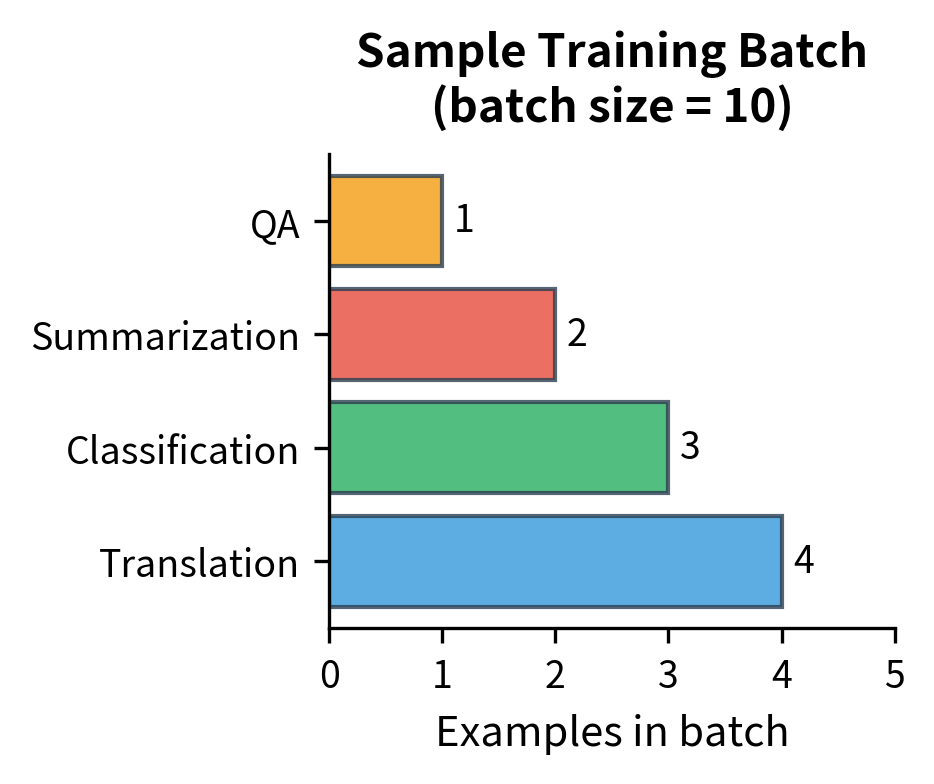

A key consequence of unified task formatting is the ability to train on multiple tasks simultaneously. This is not just a convenience. It's a different training paradigm that enables positive transfer between tasks. A single training batch can contain translation, summarization, classification, and question answering examples.

T5's original training mixed examples from many tasks, with task proportions tuned to balance learning. This multitask setup enables the model to develop robust representations that transfer across tasks. Skills learned from translation may help summarization, and reasoning from QA may improve classification. The shared encoder learns representations that capture linguistic information useful across tasks, while the decoder learns flexible generation strategies.

The intuition behind why multitask learning helps is that different tasks emphasize different aspects of language understanding. Translation forces the model to deeply understand semantics to preserve meaning across languages. Summarization teaches compression and salience detection. QA develops reasoning and fact retrieval. Classification hones the ability to capture document-level properties. When these tasks share parameters, the model must develop representations that serve all these needs. Such representations tend to be richer and more robust than those learned for any single task.

Limitations and Practical Considerations

While the text-to-text paradigm is elegant, it introduces several challenges that practitioners must navigate. Understanding these limitations helps in deciding when the paradigm is appropriate and how to mitigate its weaknesses:

-

Generation overhead: For simple classification, generating text tokens is more expensive than predicting a single softmax over labels. A classifier might output a 2-dimensional probability vector. T5 must autoregressively generate the label text. For high-volume classification applications, this overhead matters. A traditional classifier might process thousands of examples per second, while a generative approach might be an order of magnitude slower.

-

Output format consistency: The model might generate valid but unexpected outputs. When asked for sentiment, it might output "positive" or "very positive" or "I think positive" depending on training data variations. Robust parsing and validation are essential. In production systems, you'll need to handle malformed outputs gracefully, whether by retry, fallback, or flagging for human review.

-

Error accumulation in structured output: When generating complex structured outputs like entity lists or JSON, early errors can cascade. If the model makes a formatting mistake partway through, the remainder may be unparseable. This differs fundamentally from traditional structured prediction, where each output position is typically independent.

-

Vocabulary constraints: T5's SentencePiece vocabulary affects what outputs are efficient to generate. Uncommon labels or domain-specific terms may require multiple tokens, introducing potential for errors. If your task requires outputting rare technical terms, the model must correctly generate multiple subword tokens in sequence, and each token is an opportunity for error.

-

Length bias: The model may learn spurious correlations between task prefixes and output lengths. If all sentiment training examples have one-word outputs, the model might struggle with more nuanced labels. Training data diversity is important not just in content but in format.

Despite these challenges, the benefits of unification generally outweigh the costs for most applications. The ability to fine-tune a single model on diverse tasks, share representations across domains, and handle new tasks with minimal architectural changes has advanced NLP system design. This text-to-text approach laid groundwork for the instruction-following capabilities we'll explore in later parts of this book.

Key Parameters

The key parameters for T5 task formatting are:

- max_length: Maximum input sequence length for tokenization. Longer inputs are truncated. T5 variants support different maximum lengths (512 for t5-small/base, 1024 for larger variants).

- max_new_tokens: Maximum number of tokens to generate in the output. Controls output length and inference time.

- num_beams: Number of beams for beam search during generation. Higher values explore more candidates but increase computation.

- skip_special_tokens: Whether to remove special tokens (like

</s>) when decoding generated output to text.

Summary

T5's text-to-text paradigm transforms NLP by unifying all tasks into sequence-to-sequence generation. Task prefixes signal which operation to perform, while consistent formatting enables multitask training and transfer learning. Classification becomes generating label text, NER becomes listing or marking entities, and QA becomes generating answers from questions.

The key insights from this chapter:

- Task prefixes act as routing instructions, conditioning the model on which transformation to apply

- Classification as generation works by having the model output label text, with probabilities recoverable from decoder logits

- NER as generation can use either entity listing or inline markup formats, each with different tradeoffs

- QA naturally fits text-to-text, enabling both extractive and abstractive answers

- Multitask training becomes trivial since all tasks share the same input/output format

- Robust output parsing is essential since generated text may vary from expected formats

The next chapter introduces BART, another encoder-decoder model that takes a different approach to pre-training while maintaining similar flexibility for downstream tasks.

Quiz

Ready to test your understanding? Take this quick quiz to reinforce what you've learned about T5's text-to-text task formatting.

Comments